Harnessing the Second Axis of Positioning

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 10

, NUMER 8

Positioning is one of the foundations of effective marketing. Unfortunately, positioning is also one of the most confusing terms in marketing. (Except maybe “branding,” but that’s a topic for another issue.) And, as it turns out, when it comes to creating an effective marketing strategy for your life science organization, positioning is one of the […]

Positioning is one of the foundations of effective marketing. Unfortunately, positioning is also one of the most confusing terms in marketing. (Except maybe “branding,” but that’s a topic for another issue.) And, as it turns out, when it comes to creating an effective marketing strategy for your life science organization, positioning is one of the easiest things to get wrong.

Harnessing the second axis of positioning

In this issue I’ll review the axes of differentiation, and examine how the second axis—articulation—can be harnessed to create higher revenues. (Are you facing price pressure? Does your offering look similar to your competitors? This is something you need to understand.) I’ll use a common example to show how effective articulation can lead to prices premiums of 100% or more. And I’ll explain how you can apply this framework to your own life science offering.

The two axes of positioning.

In the last issue, I introduced the two axes of positioning. Because I’m sure you’ve been thinking about nothing else, you’ll remember the single purpose of choosing a position: to create a meaningful distinction between you and your competitors.

For those who need a refresher, here’s how I defined positioning: your organization’s conscious effort to select attributes that you want clearly specified audiences with clearly defined needs to associate exclusively with your offering/organization.

The operative word here is “exclusively.” You’ve got to be seen as unique. Which is why differentiation is crucial. Without it, you’re in trouble.

Why all this focus on differentiation?

Just to be completely clear: I’m focusing on differentiation because this is a real challenge, particularly in our industry. Regulations tend to homogenize both work product and work process. They also tend to restrict the ways in which companies can differentiate themselves.

Many organizations don’t do enough to differentiate themselves. They (consciously or unconsciously) accept that the restrictions imposed by regulatory bodies not only restrict their work, but also the way they might talk about it. As a result, these organizations tend to look and sound alike, lapsing into a status not far from commoditization. And as we all know, commodities have no pricing power.

Of course, I fully understand and support having regulatory agencies maintain standards ensuring that work process and work product meet specified quality measures. But too many organizations let those restrictions also restrict their competitiveness.

That’s wrong, and it’s just a shame.

The two axes of differentiation.

If you’re serious about lifting yourself out of commodity status, there are two axes that can be employed as you choose an effective position.

Figure 1: These are the two axes through which you can strengthen your competitive position: functionality/benefits and articulation/behavior. These two axes are independent of each other.

The first axis harnesses functionality and benefits. In other words, you can strengthen your competitive position by distancing yourself from your competitors through the uniqueness of the functionality and benefits you offer your prospects. For this to work, of course, there must be a real, meaningful difference in the functionality/benefits that you offer.

The second axis harnesses your “articulation”—which includes the language you use, your tone of voice, and the look and feel you project out into the marketplace. Another way to think about this axis is to understand this as your organization’s “behavior,” that is, the evidence of how your organization acts in public: what you say, how you say it, etc.

In the language of math and physics, these two axes, articulation and functionality/benefits, are orthogonal. That is, they can be harnessed independently to achieve your aims.

The upshot is that you can create uniqueness through your articulation; it is a powerful way to prevent your offering being commoditized. As we’ll see, effective articulation can lead to much higher sales prices. And even better, it’s not an either/or proposition.

Strengthen your position by harnessing both axes.

Companies that are extremely capable in engineering, development, and/or delivery tend to emphasize the first axis (functionality/benefits) in their marketing, sometimes relying on this axis exclusively. But as we’ll see, advantages on this first axis tend to diminish over time.

Companies that are very capable in marketing will use both axes to strengthen their competitive position, regardless of their uniqueness on the first axis. In other words, companies that have few differences between the functionality/benefits they offer their prospects (compared with that of their competitors) can improve their competitive position by harnessing the second axis. And companies that have major differences between the functionality/benefits they are able to offer their prospects can further enhance the perceived differences with their competitors by also harnessing the second axis.

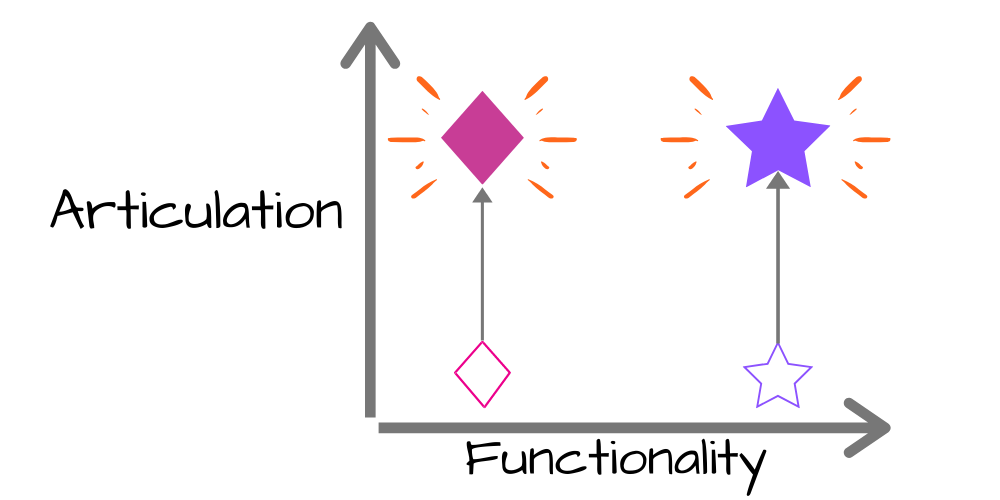

Figure 2: Whether there are large differences in your functionality/benefits between you and your competitors or not, harnessing the second axis (articulation) can help increase your perceived differentiation.

Differentiation through articulation: it really works.

Articulation can be an effective differentiator. To find examples, we need look no farther than the world of CPG (consumer packaged goods). This marketplace is often characterized by little differentiation in functionality/benefits.

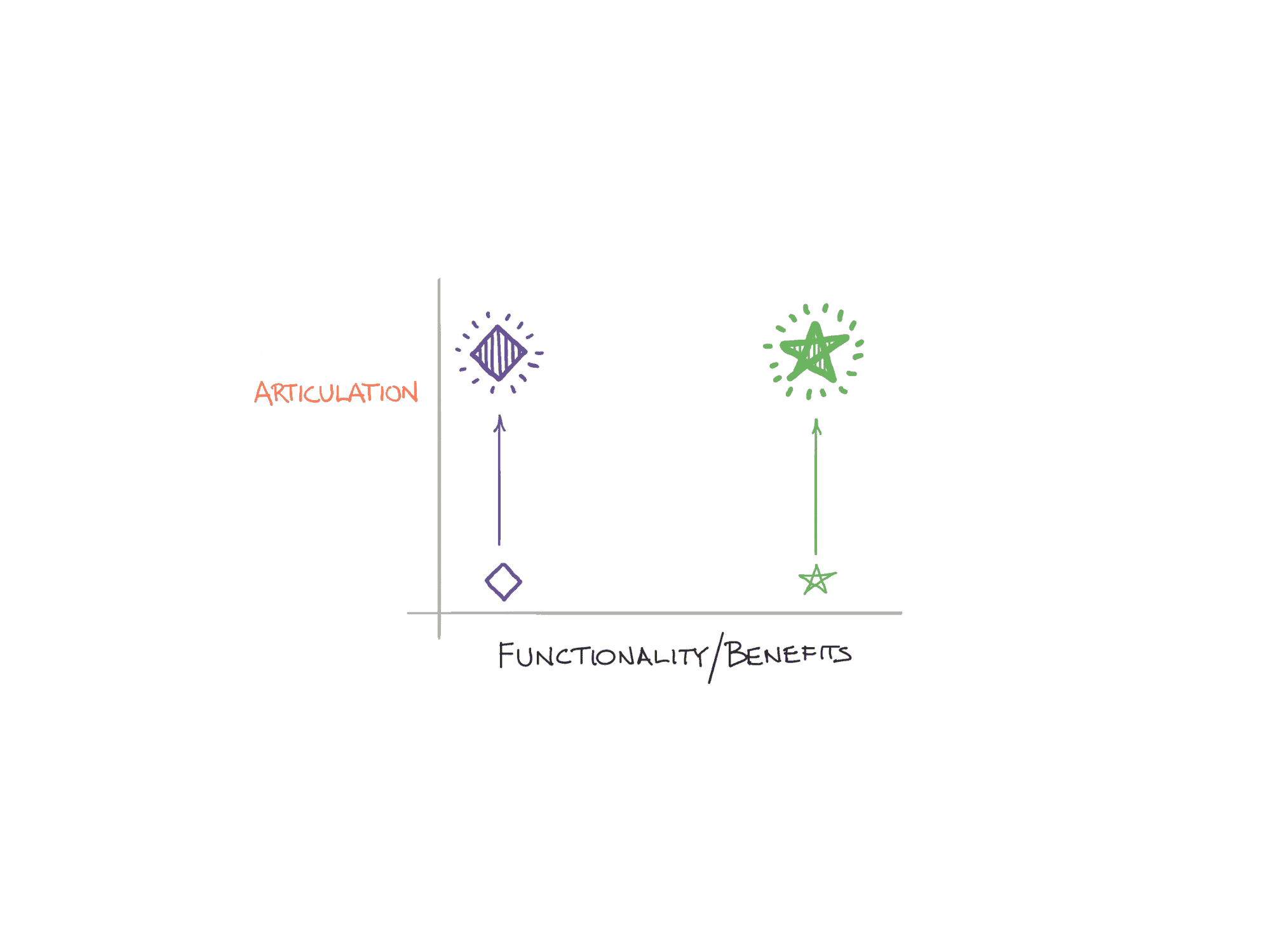

Figure 3: For most people, the difference in bottled water isn’t in the H2O itself. If the liquid in one container was suddenly replaced by the liquid from another brand, no one would be able to tell whether their thirst was more or less satisfied. In other words, there is no difference between these products on the functionality axis.

A true commodity: bottled water.

Let’s look at a true commodity: bottled water. If you were to pour two different brands of bottled water into drinking glasses, could you tell the difference? Unless you’re a highly trained water sommelier, of course not; the samples have the same taste, the same texture, the same refreshing quality of “wetness.” There is really no way to tell the difference between the products. In other words, there is no difference on the functionality/benefits axis.

Unflavored bottled water is as close to a commodity as you can get. Looking at the marketplace, you might expect significant price competition, with the cheapest offering dominating the sector. But this is not the case. Ask yourself: do you always buy bottled water strictly on price? For most people, the answer is, “no, not always.”

You see, bottled water manufacturers don’t simply accept their commodity status. In figure 3 you see several strategies for differentiation: Bottle shape and texture, label size, label colors, type style, images used on the label, cap color, cap style, amount of water, etc., etc.

These organizations understand that commoditization means failure. These organizations have a lot to teach us.

All bottled water is the same on the inside. But not on the outside.

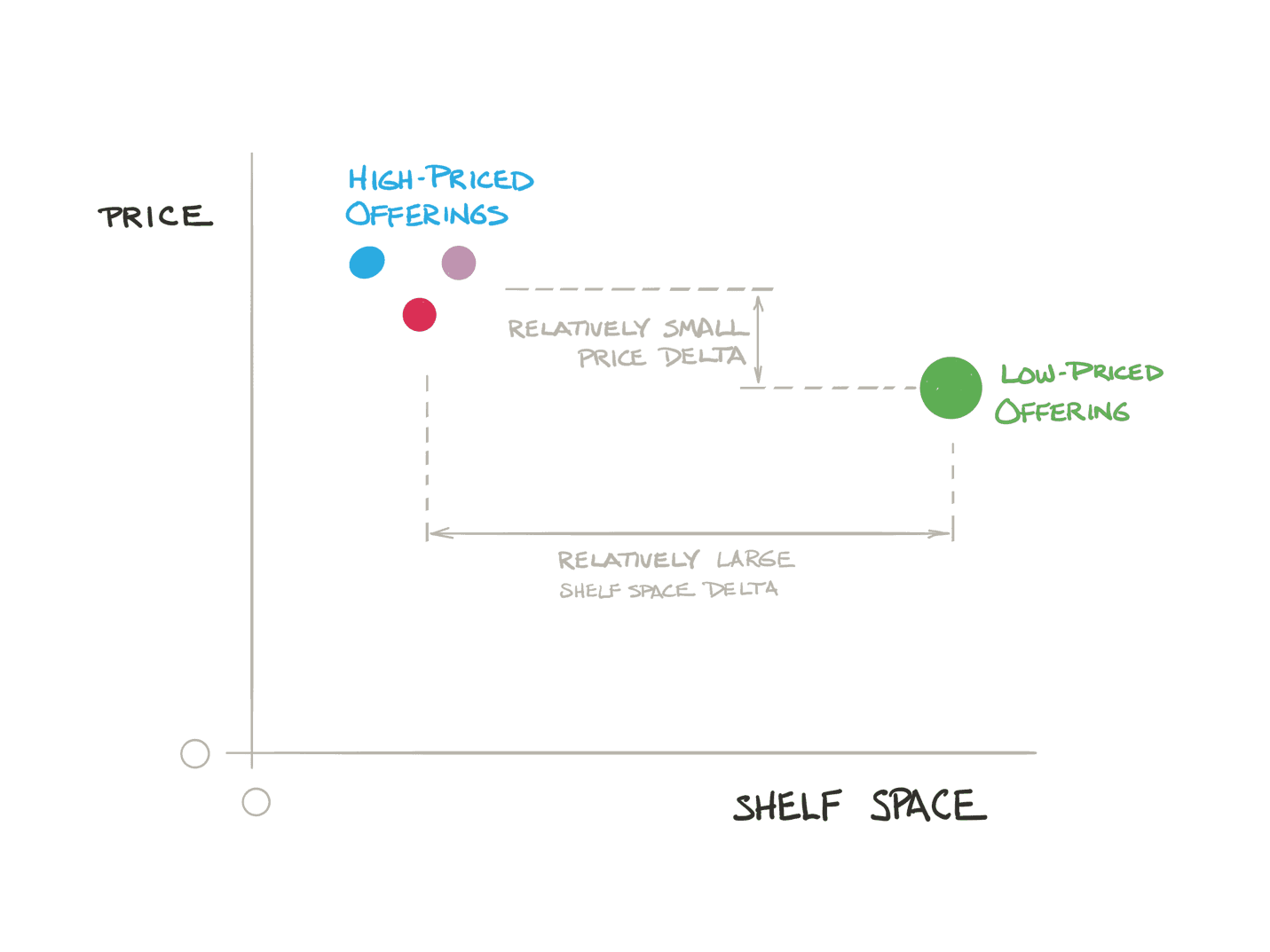

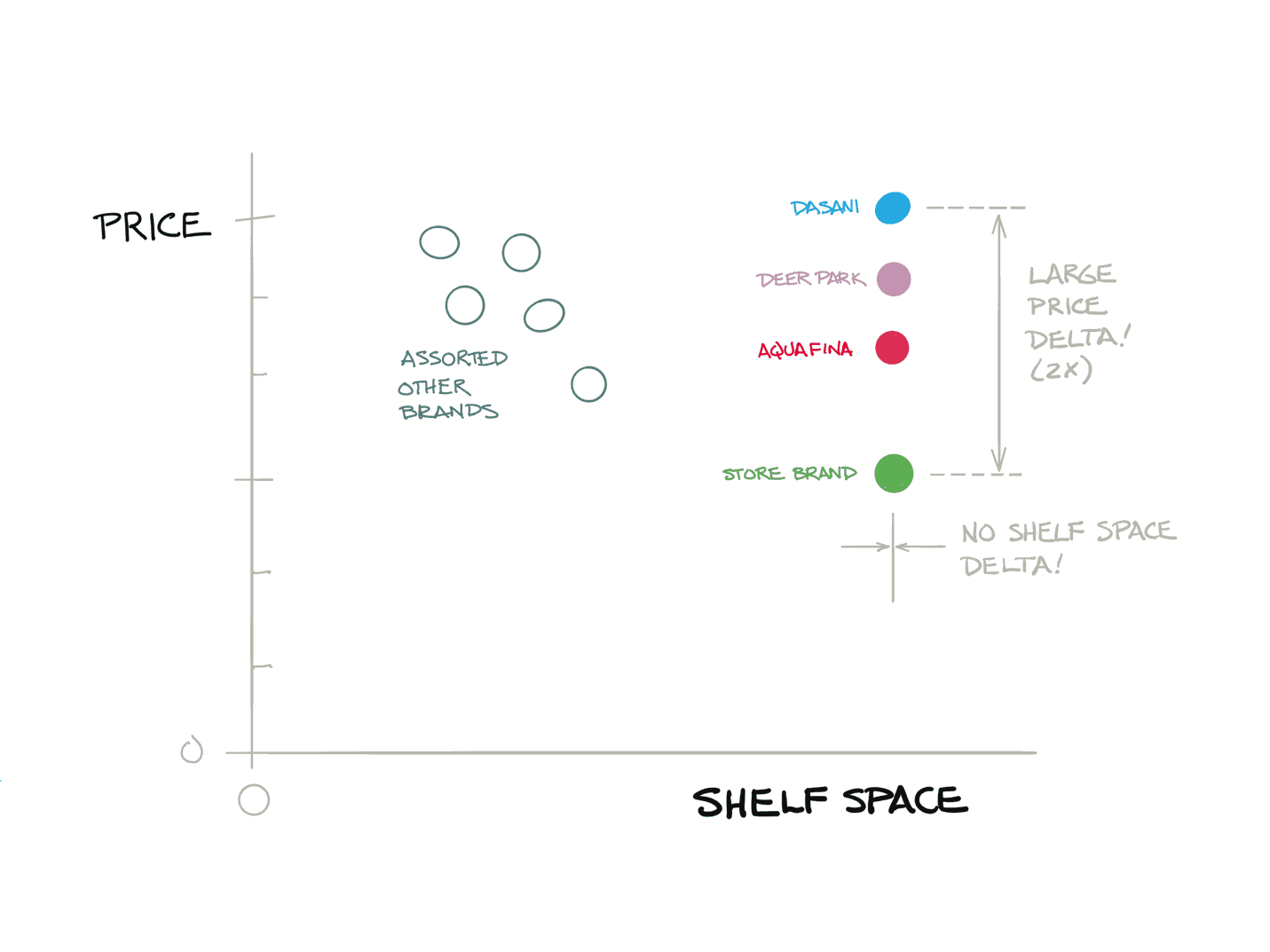

My local grocery store, like most, has a significant part of an aisle devoted to bottled water. If price was the only decision criteria that shoppers used in that store, the shelf space would be dominated by the lowest-cost brand, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: If the bottled water market was truly a commodity market, it would be driven by price alone. We’d expect to see what economists call a “relatively flat demand curve” where the sales volume is extremely price sensitive. That would lead to the relationship between the amount of shelf space devoted to each product and the price that is shown here. The branded, more-expensive products would have very small market share, and therefore, very little shelf space. Because we’d expect little difference between products, the price premium that a high-end offering would be able to charge would be very small.

But that’s not the case in my local grocery store; it doesn’t devote the most shelf space to the lowest-cost product. There is actually significant shelf space devoted to more-expensive brands. Figure 5 depicts the research I did in this store; other stores in the area had similar results—one had 15 different brands of bottled water. That’s right, 15! That’s hardly evidence of commoditization.

Figure 5: My local grocery store doesn’t devote the vast majority of its shelf space to the cheapest bottled water brand; the data is shown here. In fact, higher-priced products get significant shelf space. Differentiation must be having an effect, because there is a price premium of 100% for at least one premium brand. In other words, despite bottled water being a commodity product, the marketers have fought successfully against commoditization.

Apparently bottled water is not a commodity.

If the bottled water market was truly commoditized, the lowest-cost offering would have the highest sales volume, and the most shelf space. But this is not the case, at least not in the local grocery stores I’ve surveyed. Of course, many factors besides sales volume can affect shelf space, including so called “slotting fees,” which manufacturers pay to achieve more or better shelf position. Even so, these higher-priced brands must be earning enough to pay these slotting fees. Differentiation must be working, driving enough profit to higher-priced brands to counteract the effects of commoditization in bottled water—the ultimate commodity.

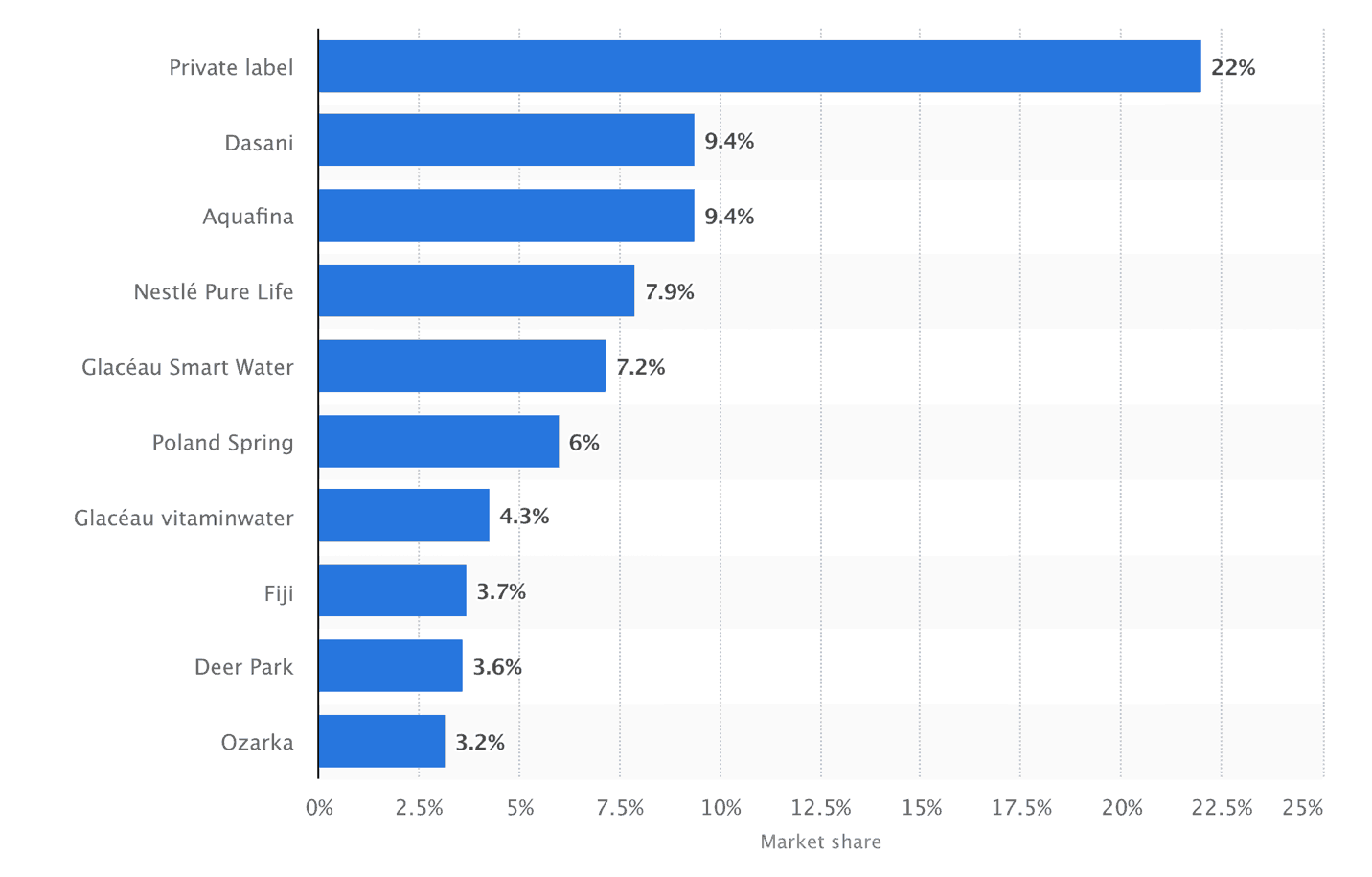

If we expand our focus and look at national sales figures, it’s clear that the low-cost providers don’t dominate the market.

Figure 6: Market share of the leading bottled still water brands in the United States in 2017, based on sales.

(https://www.statista.com/statistics/252408/market-share-of-bottled-still-water-in-the-us-by-brand/)

As seen in figure 6, even if all the private labels brands are sold as commodities at low cost (which is doubtful), the top three branded products combine for a larger market share. Differentiation is driving additional profit. Many brands, including Dasani and Aquafina, are able to compete well against commodity offerings and achieve significant sales.

Fighting against commodity status.

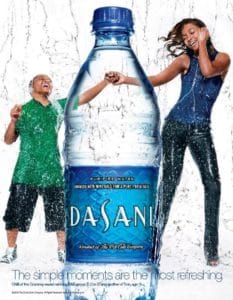

Bottled water is a commodity, with no difference on the first axis of differentiation. How do these organizations lift themselves out of commodity status; in other words, how do they differentiate? They harness the second axis of positioning—articulation. In the case of bottled water, several of the well-known brands use archetypes to create a differentiated image.

The leading brands are owned by the major soft drink companies: Dasani is owned by Coke and Aquafina is owned by Pepsi. Coke uses the Innocent archetype; Pepsi uses the Jester archetype. These archetypes also apply to their bottled water brands: Dasani uses the Innocent archetype (the same as Coke) while Pepsi uses the Jester archetype (the same as Pepsi).

Figure 7: Dasani, like Coke, is an example of the Innocent archetype. Innocents express a longing for paradise and have strong moral principles. We can see both of these trends in these ads for Dasani, referencing “simple moments” and eco-friendly behavior.

The archetypes for both Dasani and Aquafina are clearly visible, if you know how to spot the clues. These major bottled water brands are using archetypes to differentiate what is essentially a commodity.

Figure 8: Aquafina, like Pepsi, is an example of the Jester archetype. Jesters enjoy humor and like to live life fully. The promise in the headline is a humorous play on their commitment to purity.

How does bottled water, the ultimate commodity, differentiate? With no difference between the liquids inside the bottle, some products are able to achieve price premiums of 100% or more.

They do this by focusing on their brand’s articulation. If the second axis of differentiation works for the ultimate commodity—bottled water—it can work for your organization.

A word about archetypes.

As the bottled water example reveals, archetypes can help clarify your articulation. Archetypes, when used correctly, define your organization’s “tone of voice,” leading to clearer and more consistent communication. Archetypes resonate with audiences and create differentiation. As I’ve mentioned before, archetypes can drive higher profit.

The differences between the two axes of positioning.

Both axes can enhance the perceived differences between you and your competitors. But it’s worth examining the main distinctions between the two.

Difference #1: The second axis is often undervalued.

For the technically trained—that is, for many folks in the life sciences—a desire for data and proof biases them towards a belief that the only difference that matters is in functionality/benefits. As I mentioned in the previous issue, it’s possible to prove that the second axis is equally effective at creating differentiation. However, obtaining this proof requires performing quite a bit of perception research. Since this research tends to be expensive, it isn’t undertaken and isn’t typically part of marketing discussions.

This lack of proof leads to undervaluing the strength of the second axis as a tool to create differentiation. Firms that avoid this trap and use the second axis effectively can give themselves an advantage.

Difference #2: Differences on the second axis are less likely to be copied.

Competitive pressures tend to neutralize differences in the first axis over time. To see how this works, imagine you work for an organization that is #2 in market share for your main product. Your main competitor (#1) has an advantages in features and functionality. What’s your response? To catch up, of course—to close the gap on features/functionality. While you’re working to match your competitor, you might decide to compete on price, but once you meet, or exceed, your competitor’s features, you’ll be raising your price again. After all, aren’t you worth just as much as they are?

And if you do manage to leapfrog your competitor by innovating some new functions, how will they respond? By working to catch up, of course. My point? Competitors work hard to distinguish their offerings through functionality/benefits—the first axis. And over time—barring any protection from intellectual property laws—these differences tend to diminish.

But this isn’t true of the second axis—articulation. Organization’s don’t tend to copy one another’s expression in the marketplace. For example, Chick-fil-A has been using those clumsy, inventive cows for years, but how many other fast food restaurants can you name that are using clumsy, inventive cows, or even clumsy, inventive pigs? Not many.

I’m not saying there will never be any copying under any circumstances. Remember all the variations of the “Got Milk?” campaign? But this really proves the point. This copying reinforced the strength of the original campaign, and was only possible once the idea of “Got Milk?” was firmly established.

Figure 9: Unlike differences on the first axis, differences on the second axis tend to be immune to copying by competitors. How many other fast food restaurants are using clumsy, inventive animals as part of their marketing?

Differences on this second axis are less likely to be copied. So if you can establish clear differentiation using the second axis, competitive challenges will tend to come not from direct copying, but from a differentiated, unique direction.

Difference #3: The second axis offers first mover advantage.

If the way that organizations harness the second axis tends not to be copied by competitors, the second axis provides a strong advantage to the “first mover.” This requires courage and boldness. As Senator William Learned Marcy said in 1832, “To the victor belong the spoils.”

Realizing a “first mover” advantage requires two things: first, the courage to make a bold choice, and second, consistency. After all, we wouldn’t be celebrating “Just Do It” as one of the greatest taglines of all time if Nike hadn’t been bold in choosing such a simple phrase and then extremely consistent in its use, applying it over and over and over.

Difference #4: The second axis is managed differently.

The differences on the first axis arise from a different organizational function than those on the second. Differences in functionality/benefits tend to arise from R&D or operations; differences in articulation from marketing.

Your marketing efforts can create a competitive advantage for your organization, not just by creating awareness, but by creating distance between you and your competitors. The differentiation created by your marketing department can be a source of additional profit. Don’t believe me? Then revisit the bottled water example above.

How to harness the second axis.

Many life science organizations are over-resourced in sales and under-resourced in marketing. In other words, the sales function gets disproportionately more resources (money and people) than the marketing department. Short of increasing the marketing budget, how can these organizations do a good job of harnessing the second axis?

The answer has several parts. The first part is simple: courage. You have to recognize that the second axis is a valuable way to differentiate your offering and then you must commit to creating a difference using this axis. This means choosing a clear position, and a clear, unique articulation of the value you offer.

The second part is simple as well: consistency. Once you’ve chosen a position, a unique value proposition, and a unique method of articulation, you have to be consistent in your “behavior,” that is, your tone of voice and your look and feel.

The need for consistency in your articulation.

This need for consistency is why large organizations often create what are colloquially called “brand police.” Brand police work to keep the expressions of the brand as consistent as possible. Are the colors of the logo correct? Is the logo too close to another graphic element? Do we always use the tag line in the same way? Are we using the right tone of voice for our audiences?

This need for consistency is why organizations employ a brand standards manual, the bible of consistency that brand police work to enforce. In the 80s and 90s, these standards manuals got more and more prescriptive. Back when there were only a few channels (TV, radio, print) and one main activity (advertising) it made sense to put control in the hands of a small group of people—the marketing department—and to make this control as complete as possible. But this only works when the number of channels needing to be controlled is limited, and when a small group of people can actually control all public expressions of the brand.

Today, brand police are fighting a losing battle, for two reasons. First, the number of channels is exploding; social media and content marketing now occupy a greater and greater share of attention. Second, access to the market is becoming more democratic; every employee can speak to a broad audience, and many do not adhere to brand standards, if they even know that a standards manual exists.

Archetypes can help you move up the articulation axis.

These Archetypes can help with both challenges: the need to clearly articulate the value you offer, and the need to be consistent.

Archetypes help organizations make the necessary courageous choices. How? The use of archetypes can clarify the implications of the choices facing the leadership team. This is a bold claim, but we’ve seen this over and over again.

Imagine you’re trying to get your leadership team to make the tough choices. Which of the following sets of questions would you expect would yield the answers you need to move your organization forward?

Option A: “Are we willing to make a bold choice in how we articulate what we stand for?” and “Are we then willing to stay consistent, no matter what happens, or what our competitors’ salespeople say about us at the trade shows?”

Option B: “Should we present as the Sage (Disciplined, Expert, Mentoring) or the Warrior (Relentless, Skilled, Team-oriented)?”

Archetypes help take the questions in Option A out of the theoretical realm. They turn the abstract choices into actionable strategies.

Not only does the proper use of archetypes help organizations make the necessary decisions, they also create consistency. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, archetypes are patterns, and the use of archetypes harnesses the pattern-matching ability of our audiences. For audiences to recognize a pattern, it must be presented clearly and consistently.

This demand for consistency actually helps under-resourced marketing departments. If they understand the value of consistency, they’ll be able to simplify their life by casting aside the desire to reinvent their marketing effort with every passing fad. The discipline to maintain consistency will yield huge rewards, not only with audiences, but also with internal employees. If all employees know that the organization aligns around a particular archetype, be it the Warrior, the Companion, the Sage or the Sovereign, their language and tone of voice will align. We’ve seen this, too, over and over again in engagements with clients.

The proper use of archetypes will augment your brand standards, encoding the correct tone of voice into a pattern that all employees recognize, and can easily follow.

Harness the second axis of differentiation.

No matter how close to a commodity your offering is, you can create differentiation and uniqueness. Just look at bottled water, the ultimate commodity. Separate bottled water products have absolutely no difference on the first axis—functionality/benefits—but they are able to create differentiation, and additional profit, by harnessing the second axis—articulation.

These benefits are available to you. All it takes is courage and consistency.

What’s stopping you?

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.