Life Science Case Study Structure: The Optimum Solution

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 9

, NUMER 6

The perfect life science case study structure is clear. In spite of this, many case studies don't include one or more of the seven components necessary for maximum effectiveness. In this issue I'll discuss these seven components and their proper order. I'll also reveal how the focus of your case study (the overlap of your Unique Value and your Approach) can be tuned throughout your case study to increase audience engagement.

Your peer-reviewed journal article doesn’t have the right case study structure to be an effective life science marketing case study

In the last issue, I explained why a peer-reviewed journal article (PRJA) makes a lousy life science case study. In large part this is because a PRJA isn’t designed for engagement, but for completeness and accuracy.

A PRJA has two other factors stacked against it—its focus and structure. Consider that a typical peer-reviewed journal article is structured in four basic parts:

- Introduction (where the all-important Question is introduced)

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion (in which the all-important Answer is revealed)

These four parts exist to frame the all-important Question and the resulting Answer. While this focus on Question→Answer works for documenting scientific advances, it doesn’t make for a compelling case study structure. Why? In the last issue I covered the reasons in detail; the typical peer-reviewed journal article is too long, too detailed, focused on the wrong topic and aimed at the wrong audience.

In contrast, I outlined the focus of an effective case study structure: the combination of your Approach and your Unique value. Having covered the focus of an effective case study in the last issue, in this issue I want to introduce the ideal life science case study structure.

Why your life science marketing case study structure is like a fine meal

As we discuss the structure of case study structure, we must be careful not to confuse the components of that structure and the public labels used to describe them. Many case study structures you see on web sites are divided into three parts, typically labeled “Challenge, Solution, Results.” But I’ll let you in on a secret: there are more components (ingredients) to a successful case study structure than these three public labels would suggest.

This is very similar to a meal purchased in restaurants. Your server might recite the chef’s special as “Maple-glazed salmon over garlic mashed potatoes,” describing four ingredients. But we all know that there are actually many more ingredients in the dish. The glaze might contain maple syrup, soy sauce, ginger, cornstarch, garlic and pepper. And the mashed potatoes might contain garlic, cream, salt, Parmesan cheese and, of course, potatoes. Counting the salmon, that’s a dozen ingredients, not four.

These ingredients must show up in specific proportions. If you used three times as much cornstarch as called for, you’d produce a gooey mess. Or if you eliminated any one ingredient, like the maple syrup, you’d change the taste of the dish.

Tasty meals have more ingredients than the menu would suggest. Now substitute effectiveness for taste, and case study structure for meal. Effective life science case studies have more components (ingredients) than the public labels (the nomenclature) would suggest. These components must show up in specific proportions and in a specific order. If you eliminate any of these components, change the proportions or alter the order in which they appear, you’ll alter the effectiveness of the case study structure.

The components of a successful life science marketing case study structure

There are seven components of a properly structured life science marketing case study. They include:

- Introduction and context, describing the circumstances within which the case study occurred

- Goals, describing the desired end state or outcome

- Obstacles, describing the challenges that stood in the way of achieving the goals

- Solution, describing the means to addressing the challenge

- Results, describing the outcome achieved through the solution

- Benefits, describing the advantages gained from the results

- Call to action, describing the desired action we want someone to take upon reading the case study.

If you drastically alter the order or the proportion of these components—or worse yet, skip one entirely—you can alter the effectiveness of your life science marketing case study structure significantly. For example, skip Obstacles, and it might appear that any supplier could have handled this challenge. If you eliminate Benefits, your case study structure will be a story without much of an ending at all, and certainly without a happy ending.

I’m not suggesting that each and every life science marketing case study structure should follow the same rigid structure. To continue my analogy, great chefs know how to improvise, working with what they have to produce fantastic meals. But they do so based on a deep understanding of the texture, taste and even the chemistry of each ingredient, and how it combines with others. And all of this is filtered through a long history trying different recipes, learning what works and what doesn’t.

Great marketers know how to work with the specifics of each situation. And if you’re already a great marketer, you may want to stop reading right here. I’m not suggesting that all case studies follow the exact same rigid structural formula, but if you don’t have decades of experience, I’m offering a “recipe” that can act as a foundation for your efforts, so you’ve got the best chance to create a winning life science case study structure.

The focus of an effective life science marketing case study structure

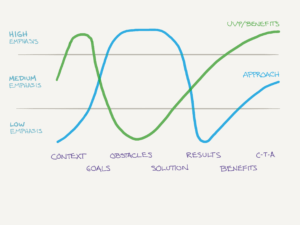

As I discussed in the last issue, the focus of your life science marketing case study structure must be the combination of your Approach and your Unique Value/Benefits. How does this dovetail with the seven-component structure of case studies that I’m recommending? It turns out that you’ll emphasize different aspects of this combination in different proportions throughout the arc of your life science marketing case study, as seen in the following figure.

Figure 1: The seven components of your life science marketing case study appear across the bottom, so the audience will read your case study from left to right. The relative focus of your case study will shift, from your UVP, to your Approach, and back to your UVP.

You’ll notice that UVP/Benefits peaks in two places, early and late. This allows you to both begin and end the life science case study by highlighting why your solution is different and better. The early components of Contest and Goals are the perfect place to introduce your Unique Value; this sets the stage for why the customer chose your solution. And the components at the end of your case study, Results and Benefits, are ideal for revealing that your customers achieved clear results, with the attendant benefits

Approach, on the other hand, peaks in the middle, during your discussion of Obstacles and Solution. This allows you to highlight the processes you used to address the challenges faced during the case study.

The focus of an effective life science marketing case study begins with UVP/Benefits, shifts to talking about Approach, and then shifts back to UVP/Benefits. Your emphasis on Approach peaks when UVP/Benefits is lower, and vice-versa. The two are countercyclical. This helps ensure audience engagement while allowing you to make the points you need to make with your case study.

THE FOCUS OF AN EFFECTIVE LIFE SCIENCE MARKETING CASE STUDY SHIFTS FROM UVP TO APPROACH AND BACK TO UVP

Again, it’s worth repeating what I said above. This advice can sound quite prescriptive, but that’s based on the fact that so many case studies I’ve looked at have such poor—and ineffective—structure.

Making the points you want to make with your life science marketing case studies

Within this framework, you can tailor your case study structure to address different goals and different buyer types. And you can use your case studies to put the emphasis exactly where you want it to be—on, for instance:

- The types of challenges you’re good at solving

- The methods you use to understand and diagnose these challenges

- The systems you use to develop alternative solutions, and evaluate their effectiveness

- How you refine and optimize the final choice

- How you then implement the optimized choice

- How you overcome challenges, difficulties or setbacks

- The impressive results you’re able to deliver

- The unique benefits your customers receive

And you’ll tailor your life science marketing case study structure using the specifics of your situation in other ways. For example, a company offering the Unique Value of unmatched depth of experience in a narrow service area would frame the Goal of their case study differently than an organization with the Unique Value of the broadest service offering.

Let your audience envision themselves in your life science marketing case study structure

These points above, as mentioned earlier, are focused on your Approach and your UVP. But there’s something else you can do with your life science marketing case studies that will further engage your audiences. And that’s to enable your Audiences to envision themselves taking advantage of a solution just like the one they’re reading about.

IT’S IMPORTANT TO HELP YOUR AUDIENCES SEE THEMSELVES IN YOUR LIFE SCIENCE MARKETING CASE STUDY STRUCTURE

Think about your prospects, the ones who are shopping for a product or service like yours. They’ve got a challenge. If they could handle this challenge, they’d solve it by themselves and they’d view it as “easy.” Since they can’t handle this challenge, they need to buy or hire a solution, and that makes it “hard.”

But having a hard challenge alone isn’t enough to get those prospects knocking on your door. In many cases, the solution you offer is completely opaque to them—they don’t know what happens inside the machine or understand every step that makes up the protocol. It’s all a “black box” to them.

Since they have no comprehension of the solution’s details, it’s difficult for them to envision a successful conclusion. If you show your prospects that you really understand their pain and if you allow them to envision their own challenge being solved, they’ll be much more likely to take steps towards that solution. As the phrase goes: “no vision, no decision.”

This is ultimately one of the key tasks of your life science marketing case study structure: to allow prospects to envision their challenge being solved. If you do this, you can help them take a step closer to purchase.

Helping your life science marketing audiences envision themselves as part of your solution

There are a few techniques you can use to help your audiences envision themselves in your case study.

- Make the case study as specific to their situation as possible. If they’re interested in creating high potency API, showing them how you’ve done exactly that will be very motivating.

- Add enough details to make the case study “real.” You don’t want to add too many details, but details will engage your audiences.

- Show “before and after.” Showing a change as a result of your involvement is crucial.

- Use metrics. Measuring your impact can help convince the scientists in the audience, the ones with a “show me” attitude.

- Emphasize the difficulty of the challenge. Not only will this support the prospects’ understanding of the situation; it also allows you to demonstrate your ability to solve those difficult challenges.

- Use testimonials. Nothing will make the case study feel more real than understanding that there’s a real customer behind this case study, one who was once in the same situation that your prospect is now.

The difference between Results and Benefits in your life science marketing case study structure

As you look at the suggested components of an ideal life science marketing case study structure, some of you may be wondering about the difference between Results and Benefits. Isn’t one of the results of our work the benefits we were trying to achieve in the first place? In other words, aren’t Results and Benefits the same thing? In a broad sense the answer to this question is yes, they are very similar.

But while Results and Benefits are similar, they are not identical. I’m separating them deliberately. The difference is significant, though admittedly subtle. Results are “what we achieved” while benefits describe “why we did what we did.” By recommending that you use a specific structure for your case studies, I’m highlighting the distinction, and encouraging you to make sure you deliberately include, and draw attention to, not only the results you delivered but the benefits you achieved.

How should you clarify the differences between Results and Benefits?

There are two ways to tease apart the difference between the Results and Benefits. The first is to focus on the what vs. the why. The second is to use a repeated question: “What did that do for you?” When asked repeatedly, this question is a very powerful way to climb up the ladder of advantages. Benefits will be located higher up the ladder than Results.

Separating Results from Benefits using What and Why in your life science marketing case study structure

These two ways to distinguish between Results and Benefits are best illustrated using an imaginary example: a consultancy that supplies regulatory remediation and training services to medical device manufacturers. One of their clients needed help; they had been issued a warning letter by the FDA and were suffering a subsequent loss of reputation and market share. To address this situation, the consulting organization conducted an audit of the client’s existing processes, compared that to best practices, designed a protocol that would address the problem, trained the client’s employees in implementing the protocol, and then guided the client through the implementation and reporting process.

Let’s apply the first method to distinguish between Results and Benefits by clarifying what they did and why they did it. What did this organization deliver? They designed a protocol and trained the client’s employees. In other words, the Results were the protocol and the training. Why did they do this? To prevent any further regulatory action, and to improve the company’s reputation, resulting in regained market share. These were the Benefits they provided. Using what vs why can help clarify the difference between Results and Benefits.

Separating Results from Benefits using “What would that do for you?” in your life science marketing case study structure

Let’s apply the second method to distinguish between Results and Benefits by repeatedly asking: What would that do for you?

What did they do? They began by conducting an audit of current practices.

What did conducting an audit do for them? It enabled them to compare current practices to best practices.

What did comparing current practices to best practices do for them? It enabled them to design a protocol and train the staff.

What did the protocol and the training do for them? This allowed them to prevent any further regulatory action.

What did preventing any further regulatory action do for them? This allowed them to rescue the client’s reputation.

What did rescuing the client’s reputation do for them? This allowed them to regain market share.

What did regaining market share do for them? It allowed them to increase their profit.

What did increasing their profit do for them? This enabled a bump in their stock price.

What did increasing their stock price do for them? This made them more attractive to investors and buyers.

What did being more attractive to investors do for them? It enabled them to position the company for sale,

…and the founders were able to receive a handsome payout,

…which enabled them to live the rest of their life in luxury,

…and go fishing off the coast of Brazil three times a year.

Using this method is powerful. If we understand that things earlier (lower) on the ladder can be considered a Result, and things later (higher) on the ladder can be considered a Benefit, then we can select the Result and the Benefit that we want to highlight in our case study. This flexibility allows us to tailor the case study to our needs. For example, the Results could be the protocol and the training, while the Benefits could be preventing further regulatory action. We might use this set of Results and Benefits to tailor our case study to prospects who were in trouble with a regulatory agency. Or the Results could be preventing further regulatory action, and the Benefits could be positioning the company for sale, which we might use to reassure prospects who are positioning their own companies for sale. Using this method of distinguishing Results and the Benefits can give us great flexibility in constructing our case studies.

Which method should you use, what vs. why or the repeated question: what would that do for you? It’s really up to you. The point here is that you need to separate Results from Benefits, calling attention to each.

The three places you’ll use a life science marketing case study structure

As I’ve pointed out, the typical life science marketing case study structure will have seven components: Context, Goals, Obstacles, Solution, Results, Benefits and a Call to Action. The proper proportion of these components will vary, depending upon where your case study appears.

You’ll use your case studies in three main channels:

- a sales presentation

- a separate (landing) page on your website

- a print version such as a downloadable PDF.

Your life science marketing case study will have a different appearance, a different structure, or even a proportion of the core components, depending upon the channel through which your audience consumes it. The appearance in each channel will be different because your readers have different expectations for each channel.

In a sales situation, the audience doesn’t want to read endless passages of text on screen. The salesperson will be conveying much of the information by speaking, so your case study should be quite visual. You shouldn’t subject your audience to “death by PowerPoint,” where you display long paragraphs of text or lengthy lists of complex bullet points. You might have short phrases on screen, to highlight only the essential points and cue the salesperson for the next topic. The relative mix of images and text will be heavily weighted towards images. By this point in a sales presentation, there should be plenty of context to establish who your company is and what it does, so you can dial down the amount of context in the case study itself.

In contrast to a sales presentation, a life science marketing case study on your web site (typically on a landing page on your web site) won’t have someone leading the audience through it step by step. And since there (typically) isn’t any audio, prospects who are interested enough to visit the page will usually have the inclination, the time, the tolerance, and even the desire to read more. Your life science marketing case study will appear in the context of your site—there will be many other messages surrounding your it. This means that the case study itself doesn’t need to provide all of the context. When presented on the web, your case study will have a roughly equal mix of images and text.

In contrast to the two previous examples, a printed life science marketing case study or a downloadable PDF must stand alone. The case study might be passed from one individual to another without any commentary. There is no web page, no speaker, no other channel conveying anything else about your organization or the context of your case study. So your case study must supply this context all by itself. In a PDF or printed version, your audience will tolerate (and in some sense even expect) a significant amount of text, and the mix of images and text will be more weighted towards text.

There are many differences between the case studies that would show up in these three different channels. Context and the relative proportion of images to text are two factors, summarized in the following table.

| Relative proportion of text to images | Amount of context included in the case study | |

| Sales presentation | Image heavy, text light | Context is less necessary, because much of the context will be supplied by the surrounding presentation |

| Landing page (web site) | Images and text are roughly equal | Context will typically come from the surrounding web site, but if this case study is on its own landing page, there won’t be as much context available. The case study must supply the context |

| Print (e.g., PDF) | Image light, text heavy | Since this form is easily to share or pass around independent of anything else, the case study must supply all the context |

Figure 2: Your case studies should be optimized for the channel in which your life science audiences will consume them. Two key differences are highlighted here: the relative proportion of text to image and the amount of context included in the case study.

My point is that the proportion of the components of your life science marketing case study will vary, depending upon several factors, including the channel through which your audience consumes it and whether the case study is written for early stage buyers (who need inspiration) or late stage buyers (who need reassurance).

Tailoring your life science marketing case study structure to different phases in the buying cycle

Earlier in the buying cycle, buyers need inspiration. Inspirational case studies are typically shorter, with a greater emphasis on UVP/Benefits. Later in the buying cycle, buyers need reassurance. Inspirational case studies are typically longer than reassuring case studies, with a greater emphasis on your Approach.

But this difference in proportion won’t be obvious to most of your readers, because the public labels you’ll use for the different sections of your case studies should be the same across all your case studies.

The public labels for the seven-component life science marketing case study

It will be easier to read your life science marketing case study if it’s divided into sections. But several of the components I’ve discussed here, such as Context or Call-to-Action, won’t take more than a sentence or two to cover. So when it comes time to lay out your case study in its final form, you probably won’t have seven sections, one for each of the components, because it doesn’t make sense to have a section that has only one sentence in it.

You’ll group the seven components into a smaller number of sections and give each a label. Most case studies I’ve examined have three sections—sometimes four. The most popular labels for these three sections are “Challenge—Solution—Results.”

In this case, the Challenge section would contain the following components: Context, Goals, Obstacles. The Solution section would contain only one component, Solution, and the Results section would contain the remaining components: Results, Benefits, and Call-to-Action.

Not every life science organization will use the Challenge—Solution—Results label. Other labels include:

- Opportunity—Approach—Results

- Diagnosis—Prescription—Treatment

- Situation—Response—Outcome—Benefits

Ideally, these labels will be guided by your position and your archetype. But no matter which set of labels you use, two things are true. First, the nomenclature you use for public consumption should be consistent across all of your case studies. Second, regardless of the public labels you use, your case study must contain all 7 components if you want to maximize its effectiveness. Omit one at your peril.

The common component missing from most life science marketing case studies

In spite of the importance of each and every one of the seven components—Context, Goals, Obstacles, Solution, Results, Benefits and a Call to Action—many life science case studies I’ve examined are missing some. And that drastically reduces their effectiveness.

For example, many life science case studies don’t begin by providing a good sense of Context. The authors assume that everyone who reads the case study will already know everything there is to know about the organization, their offering and their customers’ problems. Of course, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Many other case studies discuss Results, but without clarifying the Benefits that these Results enabled. What a missed opportunity this is.

And there’s one final component that many, if not most, case studies overlook. I haven’t mentioned this component up until now, because I’ve been fearful of opening a Pandora’s box. But it’s time to name this missing component and to tackle the complex topic that surrounds it. If you’re going to create effective case studies, you’ve got to include this component, and the way to do that is to understand and then master this topic.

The component? Tension. And the topic? Storytelling. Including tension in your case studies will drastically increase audience engagement—a fact that has been proven over and over again. And the way to include tension in your case studies is to understand stories and how they work. This is the topic I’ll start exploring in my next issue.

Summary: Effective life science marketing case study structure

An effective life science marketing case study has a clearly defined structure, with seven components:

Introduction/context, Goals, Obstacles, Solution, Results, Benefits, and Call to action. Each must be included and they must appear in this order, though of course, their relative proportion will shift, depending upon the intended use of your case study. There are three typical places where a case study is used: a sales presentation, on your web site, and in print form.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.