Why your organization needs a single narrative

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 10

, NUMER 3

Your life science organization needs a single narrative, one that’s understood by every employee. Without this “center of gravity” your employees will wander, making up and spreading whatever story they choose. The results of this are disastrous, as we’ll see in this issue. But you don’t have to let this happen to you; there is a clear alternative, and the data show just how effective this can be.

An experiment.

I’m going to start this issue with a simple experiment. You won’t need any lab equipment—this is a thought experiment. Grab your notebook and let’s begin: Imagine taking a walk through your life science organization—down the hall, out to the production floor, into the lab, the break room, the C-suite, and even out onto the trade show floor. As you go, stop the first 50 employees you meet. Ask each employee one of the following questions, and write down their answers.

- “Hey, what’s the most important thing our company stands for?”

- “What separates us from our closest competitors?”

- “Why should our customers buy from us?”

- “What one thing do you think our prospects should know about us?”

What would your colleagues say? How much variety would there be in the answers? Would everyone communicate the same message; in other words, would your life science organization have a single narrative?

Some results.

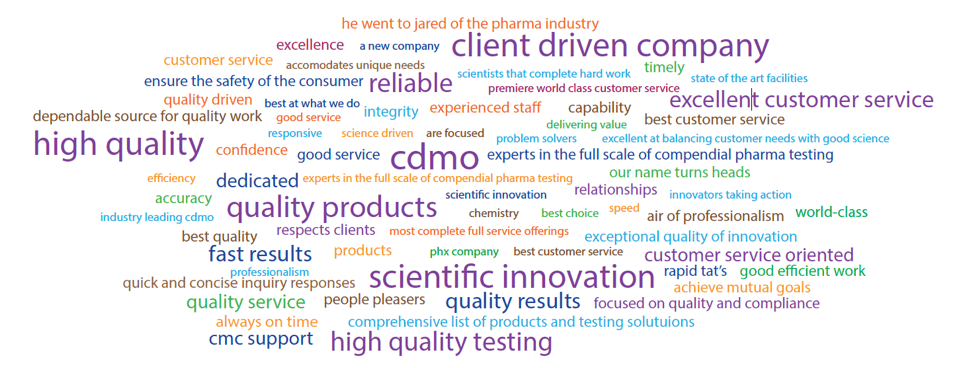

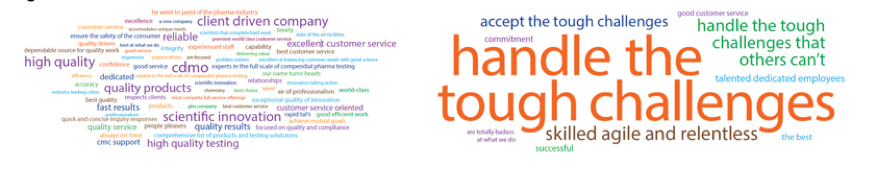

At Forma, we ask questions like these of our clients’ employees all the time. And we plot the results in word clouds. Here is one result.

Figure 1: Answers to the question: “What do we stand for?” were gathered from about 90 employees working in three US locations. What would the answers from your organization’s employees look like?

Figure 1: Answers to the question: “What do we stand for?” were gathered from about 90 employees working in three US locations. What would the answers from your organization’s employees look like?

This image is typical of the results we see. And as long as we’ve been asking questions like these, the results never fail to impress us—with their (almost) complete lack of consistency. Regardless of which life science organization we poll, most employees don’t agree on what their organization stands for. This is most likely true of other sectors as well, not just the life sciences.

In short, there is no single narrative. These word clouds are classic examples of what happens when no one deliberately shapes a life science company’s narrative and ensures that every employee understands it.

Another experiment.

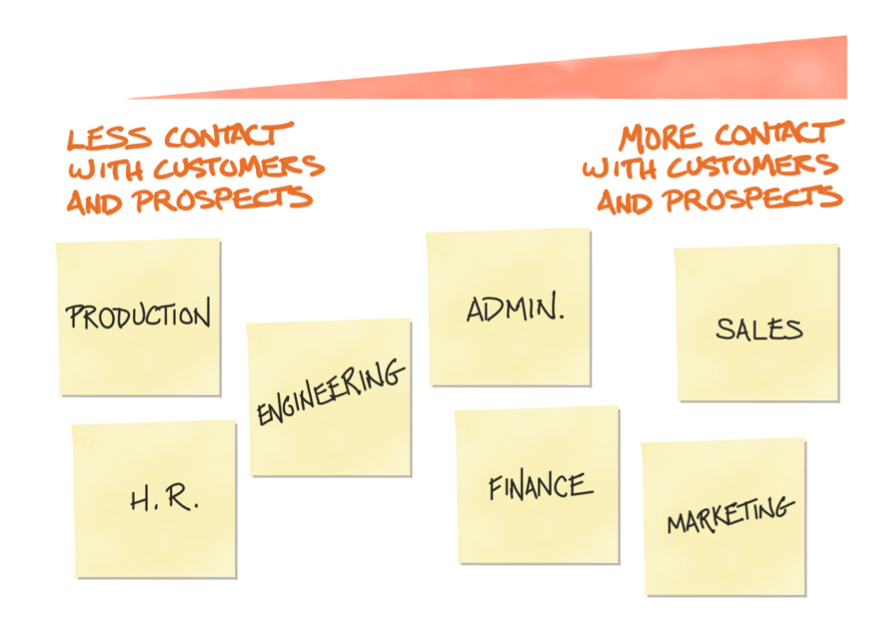

Let’s do another experiment, this one in three parts. First: Grab some Post-it® notes. Write down each of the major functions inside your life science organization, one per note. Then organize the notes into three piles. Those functions that have the most contact with your customers and prospects should go on the right; those that have none or almost no contact with the outside world go on the left; the remainder will be in the center.

What notes are in each pile? Your individual mileage may vary, but your arrangement probably looks something like figure 2.

FIGURE 2. These corporate functions are organized by how much contact they have with your life science customers and prospects.

FIGURE 2. These corporate functions are organized by how much contact they have with your life science customers and prospects.

And one more.

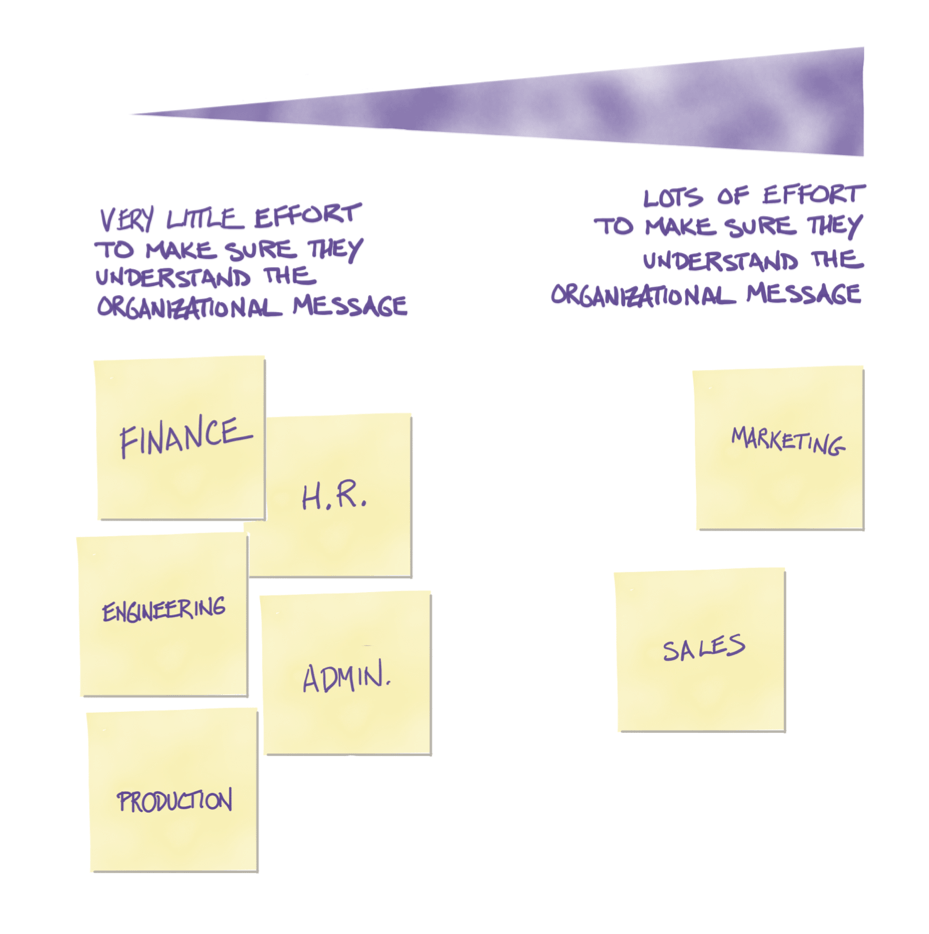

Here’s the second part of the experiment. I want you to reorganize the piles by how much effort each functional area gets, to ensure that all employees understand the corporate message (if you have one, of course).

What notes are in each pile? Your individual mileage may vary, but your arrangement probably looks something like figure 3, that is—a lot like the last experiment.

FIGURE 3. These corporate functions are organized by how much effort the C-suite puts into ensuring each functional area understands the corporate message.

FIGURE 3. These corporate functions are organized by how much effort the C-suite puts into ensuring each functional area understands the corporate message.

Now let’s shift your thinking?

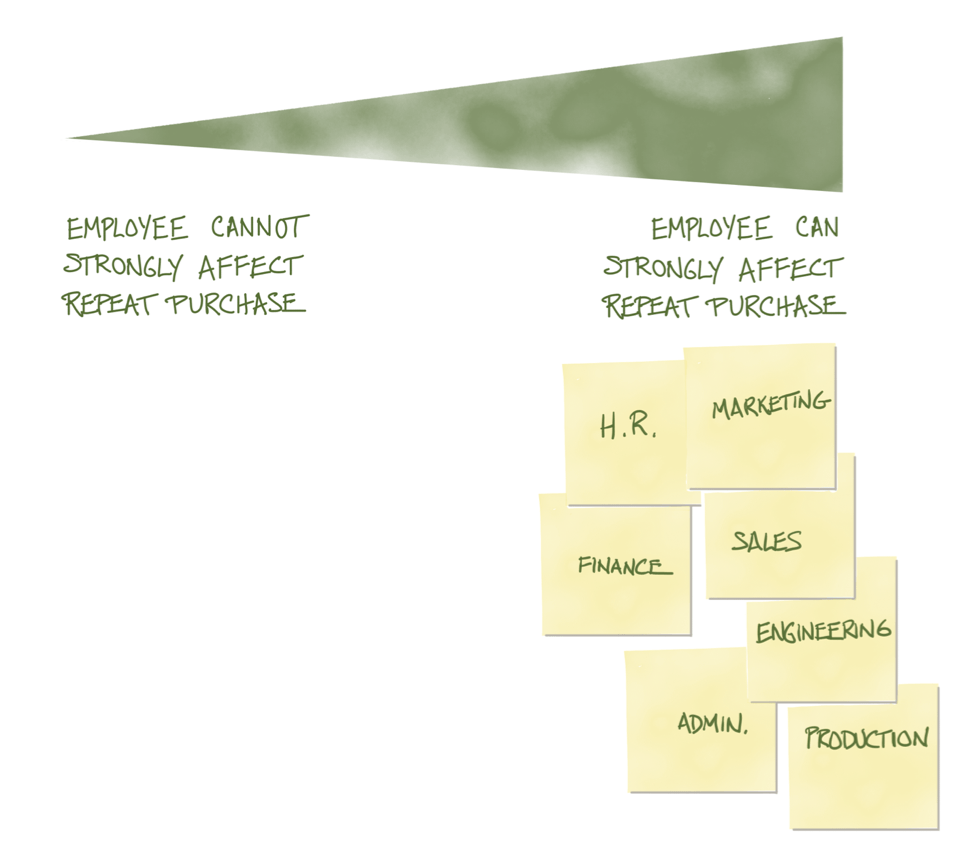

Now let’s do this once more. But this time I want you to use this organizing principle: How much can an individual employee in one of these areas affect whether or not a life science customer—having bought from you once—buys from you again? Or use this (related) question: how much can they affect whether a prospect buys from you the first time?

FIGURE 4. These corporate functions are organized by how much employees can influence whether someone buys from you—or buys from you again. The effect that most employees can have is negative, that is, it is easier for most employees to damage sales momentum than it is for them to bolster it.

FIGURE 4. These corporate functions are organized by how much employees can influence whether someone buys from you—or buys from you again. The effect that most employees can have is negative, that is, it is easier for most employees to damage sales momentum than it is for them to bolster it.

All your notes should be on the right. That is, each and every employee has a stunning amount of power about whether someone buys from you the first time—or a second time. Frankly, most of this power is negative, the power to slow sales momentum by hurting your reputation, but the power exists nonetheless.

Don’t believe me? Consider VW. A small handful of engineers decided that they were going to “game the system” and defeat the environmental testing standards mandated by the EPA. That small handful of employees ruined VW’s reputation, and in the process, ruined the reputation of diesel engines as a whole. And, yes, ruined the opportunity for untold sales of VWs.

None of those employees worked in marketing—most worked in engineering, a function that is typically considered “removed” from customers and prospects.

Or consider United Airlines. A few employees had Dr. David Dao removed off a flight in April 2017. United Airlines stock dropped by $1.4 billion, just a few days later.

Never confuse proximity with power.

The difference between Figure 2 and Figure 4 is significant. You see, most leadership teams confuse an employee’s prevalence of contact with the outside world (that is, their perceived proximity) with their power to affect future sales. In reality, most employees don’t have a lot of contact with prospects and customers, but they can still drastically affect future sales, by destroying the organization’s reputation.

In other words, while only a few employees have proximity, almost all employees have power. Don’t confuse the two. The power that employees have to affect future sales is one reason why your organization needs a single narrative.

Your organization needs a single narrative.

Almost every employee that works for your organization has a Facebook account. Many are tweeting on a regular basis. Most have a LinkedIn profile. All these employees could use these channels to affect your organization’s reputation—positively or negatively—and through that, your sales and marketing efforts.

Given that, shouldn’t all these employees know the corporate message? Shouldn’t there be a single narrative?

Do all employees in your life science organization understand your corporate message? If you don’t know the answer, revisit the first thought experiment above, the one where you’re asking the same question of every employee. How consistent are the answers?

Does your C-suite ensure that there is a single narrative, one that is commonly understood and constantly reinforced throughout the organization? This narrative must be consistent from employee to employee. If you don’t give your employees a single narrative, they’ll make up any damn thing they want. That’s what the word clouds—like Figure 1—reveal: that employees, well-intentioned as they may be, are making up their own narrative for your organization. And that’s a recipe for, if nothing else, confusion in the marketplace.

People need meaning.

People are always searching for meaning. That’s how human brains are wired; we understand the world by ascribing meaning to it. The hard-wiring in our brains predisposes us to use a very specific vehicle to organize and interpret the meaning we seek in the world. This vehicle is narrative—also known as story. Story is how humans make sense of the world.

“We think in story. It’s hardwired in our brain. It’s how we make strategic sense of the otherwise overwhelming world around us. Simply put, the brain constantly seeks meaning from all the input thrown at it, yanks out what’s important for our survival on a need-to-know basis, and tells us a story about it, based on what it knows of our past experience with it, how we feel about it, and how it might affect us.” Wired for Story Humans’ need for meaning is so great that if we aren’t given meaning, we’ll make it up. If there is no obvious meaning, we’ll invent it. This is where superstition comes from—ascribing meaning to events that may well be random. There are several names for this: apophenia, paredolia or patternicity. All of these describe the human tendency to perceive patterns (and meanings) where no patterns (or meanings) exist. “But the storytelling mind is imperfect… The storytelling mind is allergic to uncertainty, randomness, and coincidence. It is addicted to meaning. If the storytelling mind cannot find meaningful patterns in the world, it will try to impose them.” The Storytelling Animal. How stories make us human.[ii] This is so important it’s worth repeating: “If the…mind cannot find meaningful patterns in the world, it will try to impose them.” Your organizational narrative is a pattern, one that enables employees to find meaning. If you don’t give your employees a pattern, they’ll make up their own. And this is what all these word clouds that we build from employee answers (as in Figure 1) reveal: in the absence of a clear, compelling corporate message, employees make up messages to describe their organization. And unless your organization is a rare one indeed, your employees are doing the same thing. A single narrative brings clarity. But there is a way to address this. The organization shown in Figure 1 developed a single narrative. The Forma team helped them define their marketing position, a unique value proposition and the resulting narrative. Then we trained all their employees, in each of their three North American facilities. The results are easy to see. The benefits of a single narrative. Organizations with a single, consistent narrative reap many benefits, including the following. That’s a lot of benefits, right? And there’s more. All of these benefits mean that your organization will have an easier time with the following: And finally, a single narrative means that your organization is less likely to run into disasters, like those that befell VW and United Airlines. In future issues, I’ll describe how you can disseminate and maintain your organization’s single narrative. But of course, deploying a single narrative begins with creating a narrative in the first place. This narrative should be firmly rooted in your marketing position and your unique value proposition (UVP). If you don’t have your position and UVP clearly defined, start there. Because if you don’t define a narrative for your employees, they’ll make up whatever the heck they want. And the results won’t be pretty. To align your employees, to boost consistency, to control your story, begin with a single narrative. [i] Cron, Lisa Wired for Story. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2012. 8. Print [ii] Gottshall, Jonathan The Storytelling Animal. How stories make us human. Boston: Mariner, 2012. 103. Print. FIGURE 5. Answers to the question: “What do we stand for?” were gathered from about 90 employees working in three US locations. These two images show the lack of a single narrative (before training, on the left) and the strong presence of one (after training, on the right).

FIGURE 5. Answers to the question: “What do we stand for?” were gathered from about 90 employees working in three US locations. These two images show the lack of a single narrative (before training, on the left) and the strong presence of one (after training, on the right).

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.