Marketing Challenges During M&A – Relationships Among Families of Brands – Part 3

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 4

, NUMER 2

In the last of a series on this topic, we expand the applications of the model depicting different relationships among families of brands. We look at several sectors in the life sciences and notice the similarities among the approaches used. We also discuss the use of the model as a tool for planning the changes in relationships among families of brands in the midst of life science marketing challenges, such as mergers, acquisitions, divestitures and product and service launches.

How different bioscience sectors handle transitions during mergers, acquisitions, divestitures and launches.

In the last two issues we discussed a useful marketing model that depicts multiple ways that the relationships among different bioscience brands can be presented to the consumer. This model is useful for discussing and answering strategic marketing questions about the relationships among different brands within a family of brands and for illuminating the strategic marketing questions faced during mergers, acquisitions, product and service launches and divestitures.

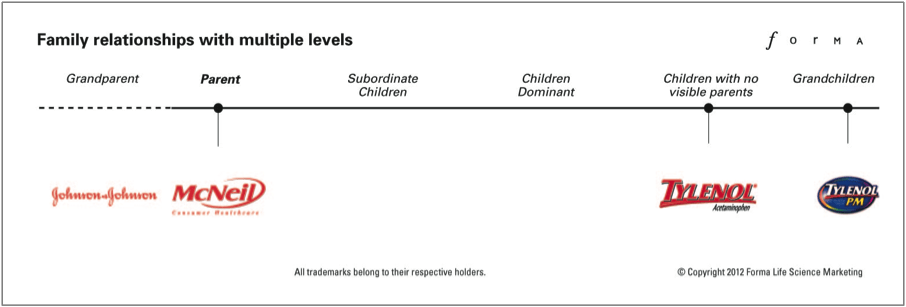

Figure 1: Shown here are four possible ways to answer the question: “How should the relationships among different brands be portrayed to the audience?” There are four basic answers: Parent only, Parent dominant (also referred to as Subordinate children), Children dominant and Children with no visible parents. Please note that all trademarks shown in this diagram belong to the respective trademark owners and their use in this diagram is for illustrative purposes only.

Extending the model when discussing the relationships between related brands in bioscience marketing.

Consider the example of Tylenol, which is shown in Figure 1 as a Child with no visible parent. What should we do with brands such as Tylenol PM or Tylenol Cold and Cough? The model will have limited utility unless it can accommodate these types of brand relationships.

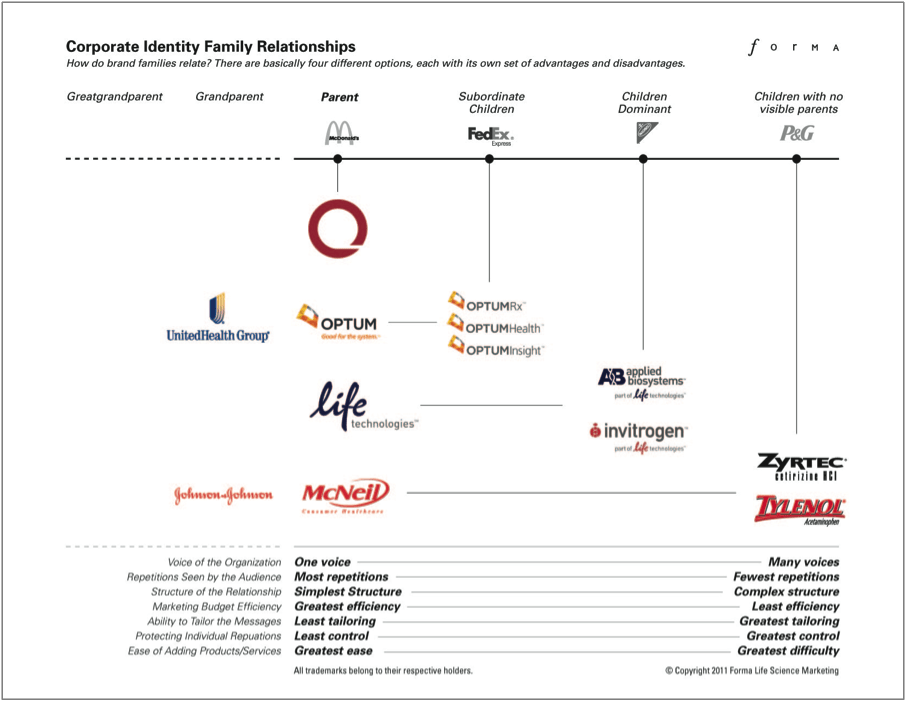

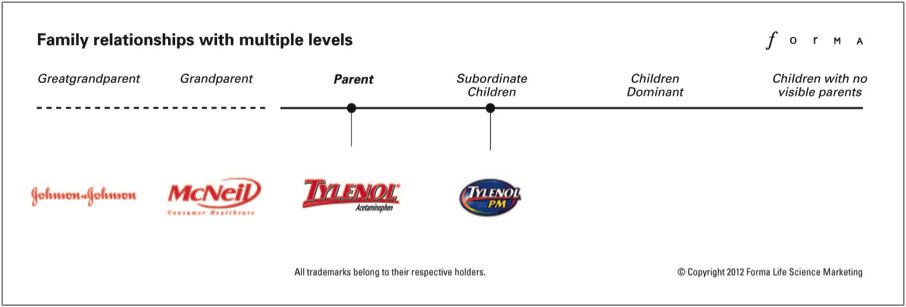

This model must be versatile enough to handle a variety of common situations.Are they grandchildren (as shown in figure 2) or should we shift the labels, so that McNeil becomes the Grandparent brand, Tylenol the parent brand, and Tylenol PM becomes an example of a child in the Parent dominant approach (figure 3)?

Figure 3: Here, Tylenol PM is depicted as a “child,” while other brands have been shifted; for example, Johnson & Johnson is now a “great-grandparent.”

Either approach can work. In one sense the labels at the top of the figure are a “sliding scale” that can be positioned to handle each individual situation. The absolute label being used is less important than the ability to address the different marketing relationships among family members in the brand family.

Despite the obvious simplicity of the model, it is flexible enough to handle either situation, and most important, either application would enable a discussion of the pros and cons of a particular marketing relationship between brands. So placing the scale in a position where McNeil is the parent and Johnson and Johnson is the grandparent brand (figure 2) would be appropriate to support a discussion of all the different “children” brands that McNeil owns, such as Tylenol, Zyrtec, etc.

One of the advantages of this model is that it provides a framework for a discussion about strategy, advantages and disadvantages. And placing the scale in a position where Tylenol is the parent brand (figure 3) could be appropriate to support a discussion of all the “children” brands in the Tylenol family, such as Tylenol PM, Tylenol Cough and Cold, etc.

This is one of the primary values of this model: it provides a framework for a strategic marketing discussion and helps compare and contrast the advantages and the disadvantages of the various possible approaches in defining the relationships among brand families in bioscience marketing.

Different approaches to marketing brand families in different sectors in the biosciences.

The model we have been discussing incorporates many different approaches that companies can follow in portraying the marketing relationships among different brands in a family. Each approach has its own set of advantages and disadvantages, all available to those marketers who choose a particular approach. For a list of these advantages and disadvantages, see the bottom portion of Figure 1.

Given these advantages and disadvantages, it should come as no surprise that certain sectors in the biosciences tend to favor certain marketing approaches, with many (if not all) of the organizations in that sector following the same approach. While there are exceptions to the examples I’ll provide here, they are useful in that they can teach us something about the general principles involved.

Approved pharmaceutical products in the biosciences tend to use a Children with no visible parents marketing approach.That is, there is typically no visible parent brand in marketing these drugs. By “visible,” I don’t mean to imply that you can’t find the name of the parent brand somewhere on the package, or even in very small type on a print ad. I do mean that at the topmost level, the parent brand is not prominent. The benefits of this approach are many:

- The marketing messages describing each individual product can be finely tailored.

- The spread of damage from one brands’ reputation to another brand in the family can be more easily contained.

- The ability to divest (or aquire) an individual brand is maximized.

From the parent organization’s standpoint, this approach also has several disadvantages, including:

- The parent organization now must maintain multiple marketing voices.

- The structure of the brand relationships presented to the audience (if they are presented at all) is complex.

- The number of repetitions of any given message seen by any audience member are the fewest of any of the brand-relationship options (assuming that marketing resources are divided among several children).

- The budget efficiency (the cost for each impression, with a given marketing budget) is lowest.

Approved pharmaceutical products tend to follow a “Children with no visible parents” approach.In the marketing calculus that happens inside pharmaceutical companies, these disadvantages are outweighed by the advantages offered by following a Children with no visible parents approach. How do I know this? Simply by looking at a formulary list when considering prescription products or by walking down the aisle in any drug store for OTC (over-the-counter) products. It is clear that almost the entire sector follows the Children with no visible parent approach, separating the ultimate parent (or grandparent) from the child.

Service organizations in the biosciences such as CROs, CMOs and labs, among others, tend to use marketing approaches from the left side of the model, such as Parent only or Parent dominant. The benefits of this approach are many:

- The parent organization has to maintain only a single marketing voice.

- The structure of the family of brands being presented to the audience is the simplest.

- The number of repetitions of any given message seen by any audience member can be the greatest.

- The budget efficiency (the cost for each impression, with a given marketing budget) is the highest.

- Adding or divesting products or services under a Parent only approach does not require the introduction of any new brands.

From the parent organization’s standpoint, this approach also has several disadvantages, including:

- The marketing messages describing each individual service (such as patient enrollment for a CRO) cannot be finely tailored.

- The spread of “perceived damage” from the reputation of one service to the entire parent’s organization is difficult to contain.

- The ability to build brand equity that would have value in a divestiture of just a part of the organization is minimized.

It is typical for these types of organizations to grow through acquisition. The acquisitions are implemented because of the synergies resulting from the combination of the new products and services with existing products and services. The fact that these synergies exist tends to reinforce the Parent dominant or Parent only model. Also, the acquisitions can occur at any time, which tends to increase the difficulty of managing a large and stable family of children brands.

Were an approach from the right hand end of the diagram to be followed, the challenge of maintaining a large family of completely unrelated brands with widely diverse backgrounds while maintaing brand consistency among all brands would be very difficult and would require individual marketing budgets for each of the brands. Prospective customers would also be less informed about the wider scope of the organization’s offerings, leading them to purchase individual services only, rather than a more inclusive assortment.

Please note that not all service organizations will follow a marketing approach from the leftmost end of the model. Here are two very specific counterexamples: it is interesting to note that Quintiles, over the course of the last several years, has varied from a Parent dominant approach to a strict Parent only approach and back again. As of this writing, Quintiles has two offspring brands listed on their website: Outcome® (A Quintiles company) and Quintiles Infosario™. Both are examples of approaches from the middle of the model. And Covance offers a fairly complete line of antibodies, at least one of which has its own brand: BetaMark™.

Figure 4: Quintiles, despite creating a brand family that relies on the Parent only approach, will occasionally venture farther to the right on the model. It will be interesting to see if the child brand “Outcome” remains, or gets subsumed within the larger parent brand. Covance offers a line of antibodies, at least one of which is branded separately: BetaMark™.

Scientific research instrumentation and supplies in the biosciences often use a marketing approach from the middle of the model, such as Parent dominant or Children dominant. This sector is characterized by technology that is constantly changing, and new products and new models are introduced frequently.

Scientific research instrumentation and supplies tend to follow approaches from the middle of the model, such as “Parent dominant” or “Children dominant” approaches. Using a Parent dominant or Child dominant approach allows the parent organization to tailor the individual messages to specific audiences while also leveraging the parent organization’s brand image.

The approaches in the middle of the model allow some tailoring of marketing messages for individual product lines, while still providing a ‘halo’ effect – either from the parent to the child brand or from the child to the parent brand.

The benefits of this “middle-of-the-road” approach are many:

- The marketing messages describing each individual product or service (such as patient enrollment for a CRO) can be finely tailored.

- An overall brand for the parent organization can still be maintained.

- The structure presented to the audience may be simple, or it may be more complicated, depending upon the number of children and the approach taken (Parent dominant vs. Children dominant).

- Adding or divesting products under this type of approach is possible without rebranding the entire organization. When adding products and services, offerings that relate neatly to an existing one can follow a Parent dominant model; offerings that do not have such a neat relationship may be introduced using a Children dominant model.

- The ability to build brand equity that would have significant value in a divestiture is strengthened. Note that the brand value for a stand-alone divestiture may be higher for an approach from the right side of the model.

From the parent organization’s standpoint, this approach also has several disadvantages, including:

- The number of repetitions of any given marketing message seen by any audience member may not be very high (depending on the number of children in the family). However, with each repetition, the parent brand can be reinforced.

- The budget efficiency (the cost for each impression, with a given marketing budget) is worse than if a Parent only model were followed.

- The parent organization has to maintain maintain multiple marketing voices: the parent voice and the voice for each child.

- The spread of damage from one service to the entire parent’s organization is difficult, but not impossible, to contain.

A contrarian view towards choosing a particular family relationship in marketing bioscience organizations.

Please note that I am not advocating that all organizations follow the marketing strategies of their peers. In fact, a good case could be made for developing a contrarian approach – seeking out a “blue ocean strategy.” Remember, the decision to follow a particular approach should be made with a long life span in mind, so I am suggesting that a careful analysis of your competitors’ approaches should be a prerequisite to making an informed decision.

Uses of the model in planning a transition from one set of brand relationships to another in bioscience marketing.

Now that we understand how the model can plot a set of static relationships, let’s discuss the advantage of this model in plotting transitions among families of brands over time. That is: the model can help plan the way that relationships among different brands might change. Companies can migrate their brand relationships to the right or to the left, and reap a completely different set of benefits by doing so.

A move to the right on the Brand Family Relationships model will decrease the dominance of the parent brand in bioscience marketing.

When companies are introducing new assets, or building assets that they may want to divest, one option is to move towards the right side of the model, either in discreet steps or in one large leap. Making this transition will provide the ability to tailor messages for each individual child, while insulating the parent and children from each other.

A move to the left on the Brand Family Relationships model will increase the dominance of the parent brand in bioscience marketing.

During mergers and acquisitions, it is not unusual to start out with many individual brands.

This model can be used to plan transitions among families of bioscience brands over time.Once these brands have been purchased, they can be placed on the model as Children with no visible parents. A strategic decision must then be made: what relationship do we ultimately want to present to the public? It would be possible to migrate some or all of the brands towards the left side of the model. This can provide multiple benefits, such as greater budget efficiency. If the decision is made to migrate the family all the way to the left, then the entire organization will ultimately be seen as Parent only which will provide the ability to maintain a single brand despite a stream of ongoing acquisitions.

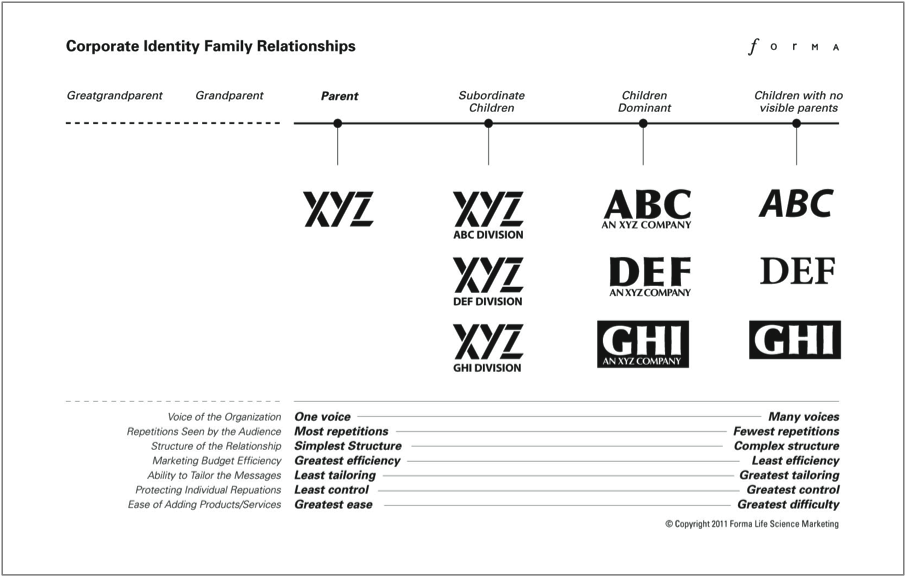

Figures 5 shows successive stages of a fictitious example. Company XYZ acquires a set of individual companies, shown here as companies ABC, DEF and GHI, each with its own brand. There are four possible scenarios for the final presentation of the family relationships.

Figure 5: During acquisition, companies frequently begin with an array of children, shown in the right-most column. Different options are shown for the ultimate approach to marketing this family of brands.

First, the individual offspring can remain as Children with no visible parents – the far right column in figure 5.

Second, the parent can be introduced through a Children dominant approach. In figure 5 the individual brands of the children remain, augmented only by a small typographic addition to the logo. This approach has the advantage of speed and convenience; it is both simple and quick to make a small change to the logos on the individual web sites. As a variation of the above, a rebranding effort could result in greater harmony among the individual logos, while leaving the presented relationships as an embodiment of Children Dominant.

Third, the parent can be made the dominant brand by following a Parent dominant approach – The second to the left column in figure 5, showing the subordination of the orginal brands to the new parent.

Fourth, the children can lose their individual identities entirely, and be subsumed under a Parent only approach – the left-most column in figure 5.

Consideration of these options is not limited to the aftermath of a merger or acquisition. Brand families do not have to be stuck in one approach forever. They can migrate over time, from one approach to another. Please be aware that a shift in approach requires both resources and the willingness to reeducate your audiences about the nature of your family relationhsips, and so must not be undertaken lightly.

An example of the use of the model in planning strategy for brand relationships in bioscience marketing

As an interesting example, Forma worked with a client during a consolidation of several similar bioscience B2B service organizations. There were 6 individual brands that were purchased to form the new “family.” This situation was similar to that shown in the far right column of figure 5, with individual children and discrete brands. Without divulging all the strategic reasons that were proposed for the various transitions, the tactical expression of our strategies took the children quickly from a Children with no visible parent approach to a Children dominant approach. Then, after a period of preparation, a new organization was launched under the Parent only approach. During this final transition, the original brands for the individual children were phased out in favor of the new parent brand.

The similarity between launches and acquisitions in bioscience marketing

While this newsletter and the previous two have been focused on the relationships among families of brands during mergers and acquisitions, it is important to note that the model we’ve developed can be used to discuss new product or service launches as well. Similar benefits will result from each of the different approaches during both launches and during mergers and acquisitions. For example, a new product launch under the Parent dominant model would achieve many of the benefits achieved by a merger under the same model.

In this sense, a product or service launch can be viewed as a “merger out of thin air;” that is, the “acquisition” of a product or service that did not exist before. Whether we are talking about mergers, acquisitions, launches or divestitures, this model can provide a theoretical framework to guide your strategic discussions and decisions.

Summary

- The fundamental question for bioscience marketers during mergers and acquisitions is: What happens to the marketing assets (the positioning, the messages, the taglines, the names, the identities and the “look and feel”) of the two (or more) organizations?

- There are four typical answers to this question.

- A parent-only model, where an entity serves as the marketing face.

- A parent-dominant model, where the parent can have many children, but the parent is the dominant marketing entity.

- A child-dominant model, where the many children are presented as more important than the parent.

- A children only model, where the parent is not presented.

- The model we have developed is a flexible one and the labels used in the model do not have to apply rigidly to all situations. As an example, depending on the circumstances it can be useful to see the same brand as the Parent or the Child. For example, Tylenol is the Child of McNeil Pharmaceuticals, but the Parent of Tylenol PM.

- Different sectors in the biosciences tend to exhibit similar patterns in their marketing approaches. For example:

- B2B service organizations such as CROs, CMOs and labs tend to favor a Parent only or Parent dominant approach to life science marketing.

- Regulated pharmaceuticals tend to favor Children with no visible parents approach to life science marketing.

- Scientific instrumentation and supplies tend to favor approaches from the middle of the model, such as Parent dominant or Children dominant.

- These sectors tend to follow a particular approach because of the various benefits available from that approach. (See the last issue for greater detail on these benefits.)

- However, not all companies in any one sector must – or should – follow the same approach to portraying the relationships among their family of brands. A compelling case could be made for a contrarian approach, but this approach must be undertaken carefully.

- This model is especially useful in planning transitions in the relationships among a family of brands. Examples of times of transition include: mergers and acquisitions, product or service launches, and divestitures.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.