Life Science Marketing Challenges During Mergers and Acquisitions — Part 1

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 3

, NUMER 9

Mergers and acquisitions are a fact of life in the life sciences. As the drug development ecosystem – which was previously vertically integrated – fragments and as the industry consolidates, mergers will become even more common. Mergers and acquisitions raise some of the most interesting challenges in life science marketing. In this issue, we open our series on this fascinating topic by identifying the key question that the life science marketers involved in any merger or acquisition must answer. We also provide a framework to understand the four possible answers to the key question.

The growth of mergers and acquisitions in the life sciences

The life science industries are in turmoil, aren’t they? This turmoil extends throughout the development life cycle. Companies focusing on selling into the earliest phase (drug discovery) face an onslaught of new technology in the form of product and service launches. These technological advances shift the expectations of the marketplace every year or two and, in some sectors, the pace is so rapid that the shifts can occur every quarter. Companies focused on selling into the pre-clinical and clinical phases are faced with the collapse of the pharmaceutical blockbuster model and the contraction of the major pharma companies. This contraction has many ramifications, including a dramatic increase in outsourcing, a flood of strategic partnerships and a wide array of mergers and acquisitions.

The key question for life science marketers during a merger or acquisition

When mergers or acquisitions loom on the horizon, the key question that marketers in the life sciences face is this: what should happen to the marketing assets in question? When I speak of marketing assets, I’m speaking of the conceptual assets, such as the brand, the name, the tagline, the position, the messages, and in some cases a marketing campaign or two. I’m not referring to the physical assets, such as a box of brochures, a website, or some hardware and graphics used at a trade show.

Since the primary reason for a merger is often financial, it’s a safe assumption that the financial structure of the merged or acquired companies is going to change. But this assumption is not necessarily true of the (conceptual) marketing assets of the organizations such as the brands – that outward-facing representation of the organizations, the positions of the organizations, the messages, the taglines and the brand stories. These might – or might not – survive intact.

The key question referred to above is so important that it is worth repeating:

What happens to our life science marketing assets during a merger or acquisition?

Mergers and acquisitions are complex affairs. They typically affect all functional areas and all employees. A complete discussion of the financial aspects or the effects on personnel or facilities is beyond the scope of this article, so we’re going to look at this situation strictly from the point of view of the marketing function.

There can be many types of mergers, including everything from a friendly union of equals to a hostile takeover. The case where one of the brands will simply disappear (a “buy and bury” acquisition) is a simple one from a marketing perspective, but there can still be complicated issues. If one of the brands disappears, is it phased out over time or does it disappear overnight?

The case where a consolidated form of both entities will continue to exist indefinitely is more complicated with regard to the disposition of marketing assets. Regardless of whether this is a merger, an acquisition, a hostile takeover, or a rescue, let’s assume that some aspect of both companies will survive. Once the announcement is made to the marketing team, the key question and its several iterations become crucial; after all, the answers to these questions determines the future of all public-facing marketing activities.

What happens to the positioning of the two companies? Should we try to keep both positions? Does one dominate, does one fade? Similarly, what happens to the messages? And to the taglines? What happens to the names and identities? What about the “look and feel” of the two companies?

These basic components – the positioning, the messages, the taglines, the names, the identities and the “look and feel” – form the core marketing assets of the merging organizations. And the questions faced by the marketing departments are the same for each of these components: Do we try to keep both – both names, both messages, both positions, both taglines, etc? If so, should they be treated equally or should one dominate? If we don’t keep both, which one disappears? And does it disappear instantly or gradually?

During a merger or acquisition in the life sciences, what is the marketing relationship between the entities?

These questions (and their many variations) can be distilled into a single overriding question: what will be the new relationship between the two (originally separate) entities? Whether these two life science entities are the companies undergoing a merger, the products being acquired, the positions, the names or the messages, the core questions remain the same: after the merger or acquisition, is there only one entity, or do both coexist? And if they coexist, which one is dominant (let’s call that one the “parent” brand, service or organization) and which one is subservient (let’s call that one the “child” brand service or organization).

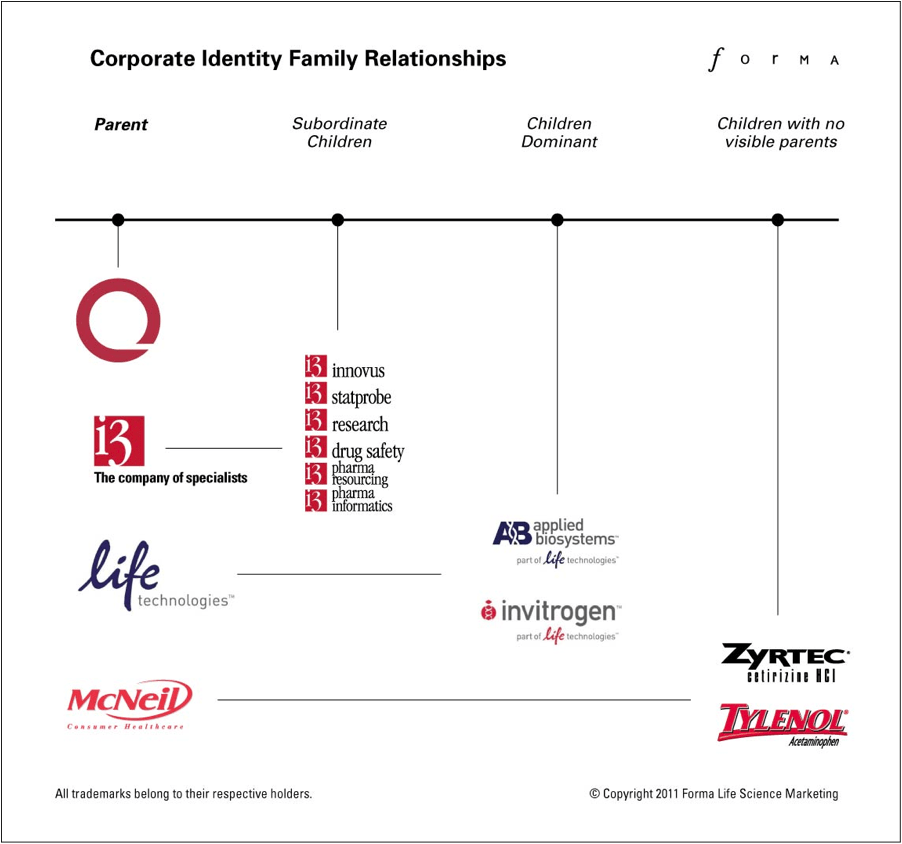

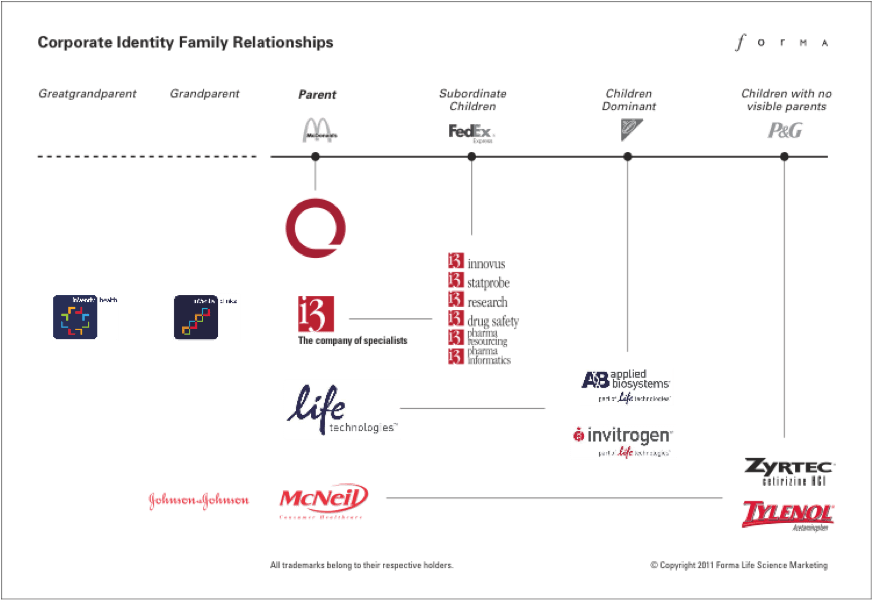

I’m going to introduce a diagram that provides a framework for understanding, modeling and discussing the four major answers to these questions. In our next issue we’ll talk about why you’d choose one answer over the others.

Here are the four answers:

a) A parent-only model

b) A parent-dominant model

c) A child-dominant model

d) A child-only model

The relationships between parent brands and children brands in life science marketing during a merger or acquisition.

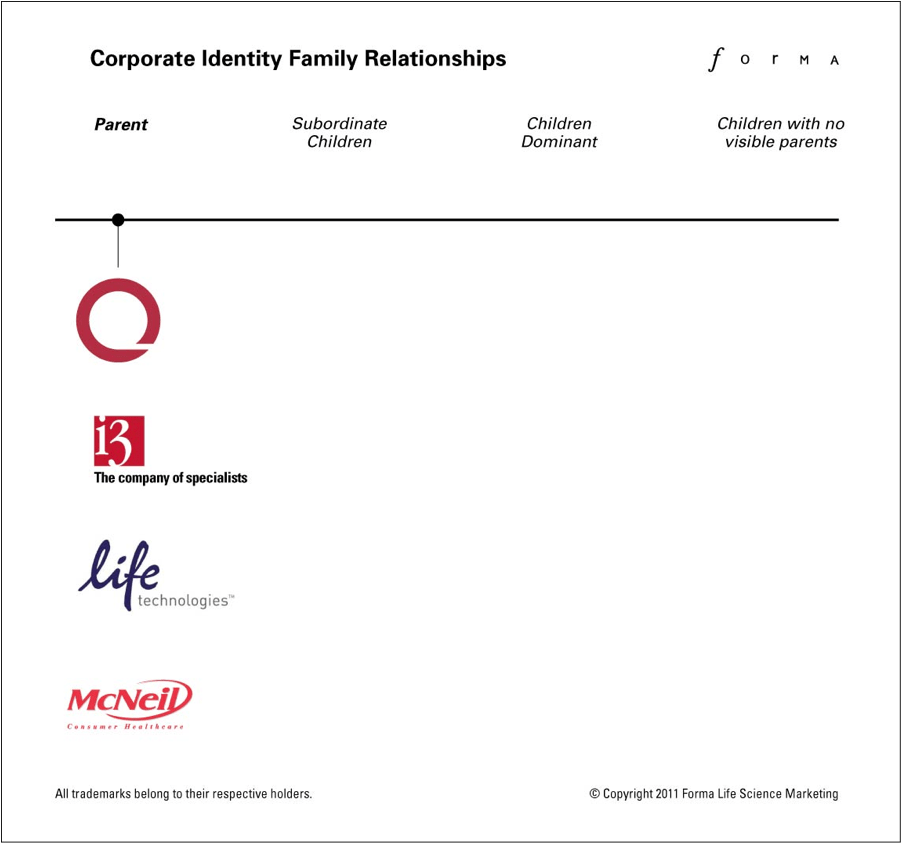

Shown in Figure 1 are four life science identities, each representing a well-known brand in the life sciences. From the top down, they are Quintiles®, i3®, Life Technologies® and McNeil Consumer Healthcare®. Quintiles and i3 are active in the sectors relating to clinical drug development, while Life Technologies services the early (drug discovery) phases of drug development and McNeil focuses on direct-to-consumer pharmaceuticals and healthcare.

Given the rapidity of change in these sectors, the examples chosen as this diagram was originally envisioned may soon be (or may even have already been) involved in a merger or acquisition. Despite any inaccuracies that upheaval in the market may introduce, the underlying concept that we’ll be illustrating in this diagram remains extremely useful to guide our discussion.

Please note that all trademarks shown in the diagrams belong to the respective trademark owners. Their use in this diagram is for illustrative purposes only.

Figure 1: Shown here are four life science brands. As we’ll see, each has a unique relationship between a “parent” brand and any “child” brands.

Each of these examples has a different relationship to other brands that it owns, or is owned by. Each of these organizations goes to market very differently and portrays the relationship between these two brands very differently. For clarity, I’ll refer to the dominant organization as the “parent” and to the less important organization as a “child.” This designation of “parent” and “child” has nothing to do with an audience of either parents or children. I’m only referring to the fact that one organization is portrayed as the larger and more important (the “parent”) while the other is portrayed as less significant (the “child”).

Life Science Marketing Brand Relationships: Children brands with no visible parent brand.

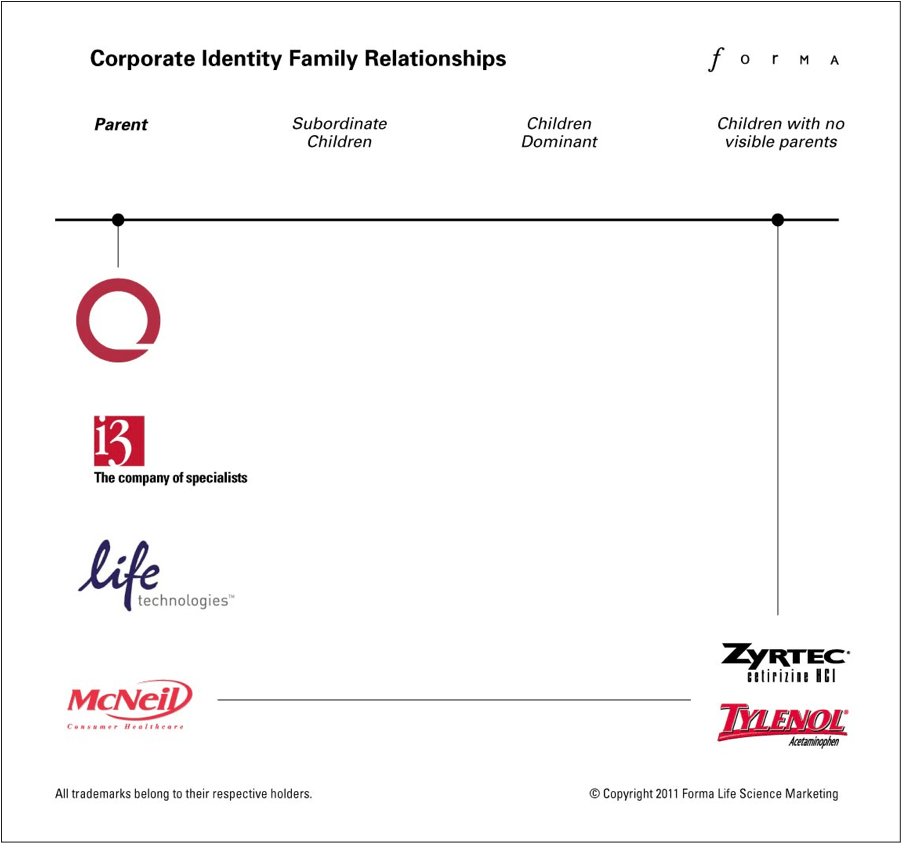

We’ll begin with one example from the four above, McNeil Consumer Healthcare. When communicating to audiences of consumers, McNeil does not promote the parent brand to any significant extent; and, in fact, most consumers do not even recognize McNeil’s name or corporate identity. They do recognize the brands of the “children” that are owned by McNeil. I’m choosing two for illustrative purposes – as shown in Figure 2, Zyrtec® and Tylenol®.

Figure 2: McNeil Consumer Healthcare goes to market by promoting their child brands. They do not promote the parent brand. This model is known as a “Children with no visible parents.”

Now, in the case of McNeil specifically, there is another major brand involved: Johnson & Johnson®, which owns McNeil. To extend the analogy of the family of brands that I am constructing, if McNeil is the parent then Johnson & Johnson is the grandparent. I’ll talk about grandparents a little later.

Please note that the brand family relationships presented by corporations depend significantly upon the audience(s) involved. If the audiences are comprised primarily of investors (stock analysts, investors, members of the financial press, etc.), then the relationships may be portrayed very differently than if the audiences are compose primarily of consumers. When reporting yearly results, for example, Johnson & Johnson typically will not spend a lot of time discussing individual children brands. Instead, they focus on the overall performance of the parent organization. In a discussion of mergers and acquisitions, the focus of this diagram is the marketing relationships to audiences of customers. A diagram that focused on communication to investors would be constructed differently.

Life Science Marketing Brand Relationships: Children Dominant.

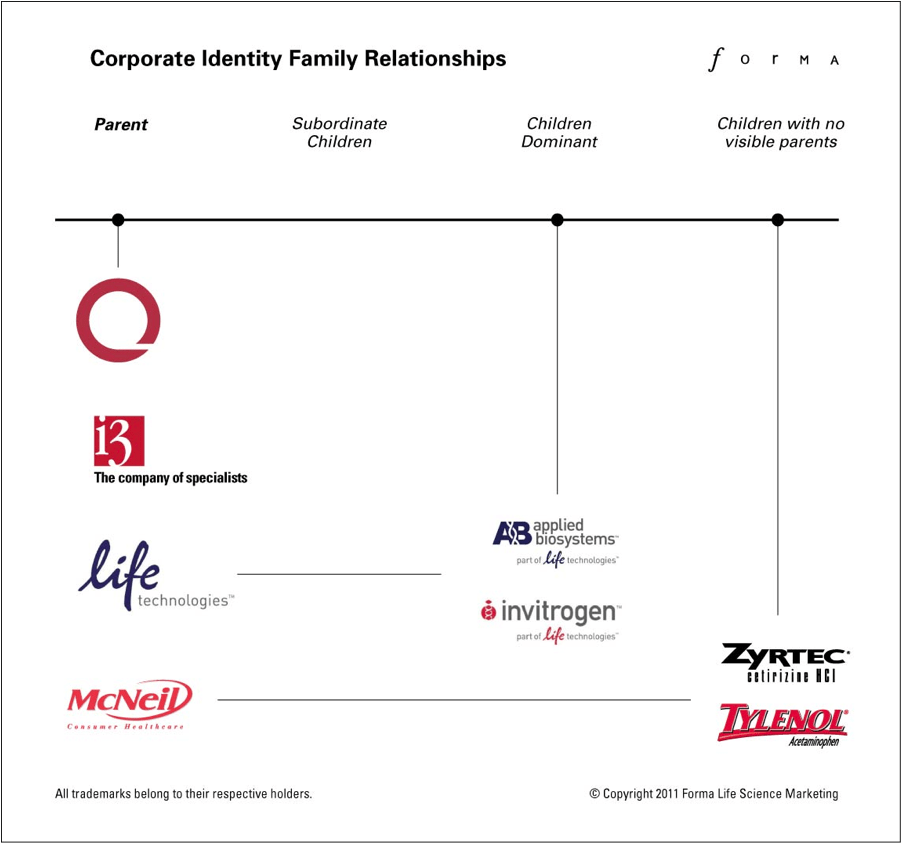

The next example from the four above, Life Technologies®, does communicate the more dominant organization (the parent) communicating to consumers, but in most cases the parent is presented as less important than the brands of the children. We refer to this model as Children Dominant.

Figure 3: Life Technologies goes to market by promoting both their children and their parent. The children are typically presented as being more prominent than the parent, so this model is known as “Children Dominant.”

Life Science Marketing Brand Relationships: Parent Dominant.

The next example also depicts an organization that promotes both the parent and the children, but the Parent Dominant model emphasizes the parent more than the children.

Of course, for either the Children Dominant or the Parent Dominant models to be valid, there have to be multiple children. In the case illustrated here, i3 has multiple children, but the parent is portrayed as more important than any of the children.

Figure 4: i3 goes to market by promoting both their children and their parent. The parent is presented as being more prominent than the children, so this model is known as “Parent Dominant.”

Life Science Marketing Brand Relationships: Parent with no visible children.

The last example (“Parent Only”) depicts an organization that promotes the parent brand alone – one that has no children. There are many examples of organizations following the “Parent Only” model in the life sciences; typically smaller organizations will follow this model.

Updates to the Life Science Marketing Brand Relationships Diagram

Given the turmoil in the life sciences, the marketing relationships portrayed in this diagram may no longer be completely up to date. Here are two examples.

For years Quintiles would acquire organizations and, to an outside observer, effectively eliminate their marketing assets. The names of the acquired organizations would simply disappear. It is interesting that this model seems to be changing somewhat. In a recent acquisition, Quintiles acquired Advion Biosciences, and the new entity is now known as Advion Bioanalytical Labs, a Quintiles Company. This is a either a subordinate child model or a dominant child model. Whether this relationship will remain will be seen in the coming months.

And it is worth noting that i3 was recently acquired by Inventiv Health, and the individual i3 children shown in this diagram seem to be fading (from a marketing perspective).

Despite any inaccuracies that changes in the market may introduce to a specific examples chosen for inclusion here, the underlying foundation for this diagram (the concept of “brand families”) remains an extremely useful analytical tool.

Retail examples of the four possible relationships

There are many good retail examples of these four possible relationships. McDonalds® is a good example of the Parent only model; despite a broad array of financial relationships such as franchises, there is only a single organization presented to the consumer. FedEx® is a good example of the Parent dominant model. The individual children (FexEx Ground®, FedEx Express® etc. all show the parent FedEx brand as more important than the individual children. Nabisco® is a good example of the Children dominant model. The individual children, such as Oreos®, are depicted as more important than the parent. And Proctor and Gamble® is a good example of a Children with no visible parents model. Little relationship between the parent and the individual children, such as Tide® and Crest®, is ever shown to the consumer. These retail examples are shown in Figure five.

Life Science Marketing Brand Relationships: Grandparents.

As I mentioned earlier, the relationships shown here are simplified for illustrative purposes and focus on the relationships presented to audiences of consumers. It is not uncommon for more complexity to exist in the real world; there can often be grandparents involved. Some of these grandparents are shown in Figure five.

Figure 5: A few grandparents are shown here. Given the rapidity of change in this sector, this diagram may be out of date by the time of publication. Despite any inaccuracies that changes in the market may introduce to a specific example, the underlying foundation for this diagram (the concept of “brand families”) remains an extremely useful tool.

This diagram can be used to depict a wide variety of complex relationships. For example, Life Technologies has many products marketed by each of its children. And many of these products have sub-brands of their own. Depicting all these products and relationships can make this model look as interwoven as the family tree of the kings of Europe for the last 400 years. While such complexity is not beyond the scope of this model, it is beyond the scope of this article, so in addition to our parents, children and grandparents, we won’t be introducing the concept of “second cousins, twice removed.”

Answering the basic marketing questions raised during a merger in the life sciences

I began this issue with a series of fundamental questions: During a merger or acquisition, what happens to the life science marketing assets in question? Do they survive intact? Do they merge together? Does one or more disappear? Do they form a hybrid?

The diagram provides a useful way to model possible answers. The choice of which answer to select will be influenced by many factors – each unique to the individual situation. Here are a few factors to consider:

- The audience(s) – their ability to understand the presented relationships

- The current “brand equity” in the two entities, including such factors as recognition, relevance and competitive position

- The strategic direction of the two entities

- The positioning of the two entities

- The size of the two entities

- The amount of competition between the two entities

- The overall marketing budget(s), etc.

While these individual factors will influence the choice of answers, each of the four possible models shown in the diagram has natural strengths and weaknesses. These strengths and weaknesses should be understood clearly before any choice is made. We’ll discuss these in a future issue.

We’ll also discuss how these different answers apply to different competitive environments within the life science sector as a whole. It turns out that particular life science sectors tend to be populated by competitors all following a particular model (e.g., Child with no visible parent, or Parent only). We’ll examine this breakdown of several different life science sectors in a future issue as well.

This diagram is also useful to model and discuss the issues related to the different ways that brand families can grow and shift over time. We will discuss this further in a future issue.

Summary

- Mergers and acquisitions are common in the life sciences; these raise great opportunities and immense challenges for marketing departments.

- The fundamental question for life science marketers during mergers and acquisitions is: What happens to the marketing assets (the positioning, the messages, the taglines, the names, the identities and the “look and feel”) of the two organizations?

- There are four typical answers to this question.

- A parent-only model, where only one entity survives

- A parent-dominant model, where the parent can have many children, but the parent is the dominant marketing entity.

- A child-dominant model, where the many children are presented as more important than the parent.

- A children only model, where the parent is not presented.

- These answers are typically focused on the marketing function and an audience of customers, rather than the financial function and an audience of investors.

- There can be more complexity in real life than is depicted in the examples given in this article, but this model provides a useful analytical tool to model and discuss this complexity.

- Many factors will influence the answer of what relationship should be chosen. Factors such as the audience, the current “brand equity”, the strategic direction of the two entities, the positioning of the two entities, the size of the two entities, the amount of competition between the two entities and the overall marketing budget are all important when choosing a marketing strategy.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.