Methods to inspire change among life science buyers (Part 2)

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 2

, NUMER 1

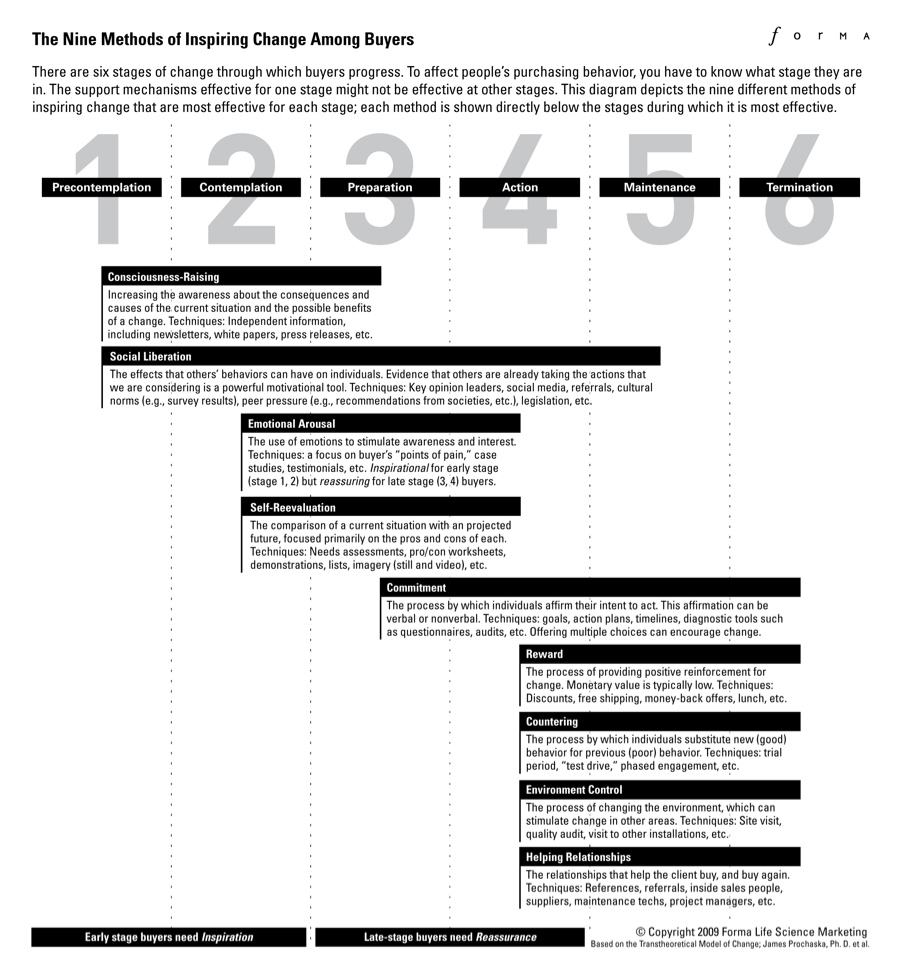

The Transtheoretical Model of Change describes the buying process via six stages through which buyers progress. There are nine methods for facilitating the transition from one stage of buying behavior to the next. In the previous issue we described four of these methods. This issue, we’ll describe the remaining five methods and provide examples from the life science sector. We’ll complete our examination by providing a diagram relating the stages of buying behavior to each of the nine methods for instigating change from one stage to the other.

A blueprint for buying behavior

Individuals progress through multiple stages as they move through the buying cycle. The stages consist of:

- Stage 1: Precontemplation

- Stage 2: Contemplation

- Stage 3: Preparation

- Stage 4: Action

- Stage 5: Maintenance

- Stage 6: Termination

If you want to affect people’s purchasing behavior, you must identify the stage that they currently occupy, and provide the support appropriate to their particular needs at that stage. This can assist the individual in moving from one stage to the next and will increase the number of individuals who eventually end up ready to take action – that is, to buy. Individuals can remain at some stages (in particular, Stage 2, Contemplation) almost indefinitely, so understanding how to facilitate buyers in progressing to the next stage is important.

The first four methods of inspiring change

In the last issue we identified and described the first four methods of change. Let’s summarize these briefly here.

Consciousness-raising (to help individuals move from Stage 1 to Stage 2 to Stage 3)

Consciousness-raising consists of providing information to a buyer to enable him or her to see the relevant issues in a new light. Many people in Stage 1 Precontemplation lack the information to perceive their needs clearly; they are naturally suspicious of any attempt to encourage them to change – seeing these attempts as self-serving.

Supplying unbiased information is a powerful method of consciousness-raising; a review from an independent source, a podcast, a recording of a lecture at a symposium, a journal article, a white paper – all these can assist in altering individuals’ perceptions.

Social liberation (to help individuals move from Stage 1 to Stage 2 to Stage 3 to Stage 4 to Stage 5)

Social liberation is the effect that others’ behavior can have on an individual; it involves the recognition of alternatives while offering support for individuals who might be considering changing their behavior. Evidence that “other people” are taking actions that we are considering can be a powerful motivational tool; people are greatly influenced by the actions of others. Robert Cialdini in his book, Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion, calls this phenomenon “Social Proof” and states: “The tendency to see an action as more appropriate when others are doing it normally works quite well. As a rule, we will make fewer mistakes by acting in accord with social evidence than contrary to it. Usually, when a lot of people are doing something, it is the right thing to do.”

There are many examples of social liberation in the biological sciences, including the influence of peers, KOLs (Key Opinion Leaders), social media, and legislation, among others. Customer lists are a prime example of social liberation, revealing highly regarded institutions that have bought particular instrumentation systems: “Oh, if XYZ teaching hospital uses this, then we should consider it as well.”

Emotional arousal (to help individuals move from Stage 2 to Stage 3 to Stage 4)

Early stage buyers need inspiration, and emotions can play a pivotal role in creating and heightening inspiration.Emotional arousal is the use of emotions to stimulate awareness, interest and ultimately, behavior change. Emotions are powerful motivators and can stimulate individuals as they move through several stages in the buying cycle. Early stage buyers need inspiration, and emotions can play a pivotal role in creating and heightening inspiration.

Examples of emotional arousal abound in the life sciences, including, stories, testimonials, KOLs, and pleas from patients, among others.

Self-reevaluation (to help individuals move from Stage 2 to Stage 3 to Stage 4)

Self-reevaluation, also known as “envisioning,” is the process by which individuals compare their current situation with an imagined future and weigh the pros and cons of the purchase in question. Often this evaluation involves a critical view of the present – focusing on the cons of the current situation – and an optimistic view of the future, imagining the future once the purchase has been completed.

Examples of envisioning include providing imagery, such as photographs, videos, floor plans or dimensioned drawings of equipment, and lists of pros/cons. Other techniques might involve helping the buyer imagine an alternate future, such as with a different workflow or algorithm that could improve process efficiency once the purchase is complete.

Having summarized the first four methods of inspiring change, let us now move on to the remaining methods.

Helping prospects move from Stage 3 Preparation to Stage 4 Action.

In contrast to Stage 1 Precontemplation and Stage 2 Contemplation (where buyers can remain for years), buyers typically remain in Stage 3 Preparation for only a short time. Because of this, time is of the essence; being in touch with buyers and providing them the appropriate support at the right time is crucial in helping them make the transition successfully.

Late-stage buyers are planning to take action in the near future, including a shift from focusing on the past to focusing on the future and a shift from focusing on the problem to focusing on the solution.Stage 3 and Stage 4 buyers are known as “late-stage” buyers. They are planning to take action in the near future, including a shift from focusing on the past to focusing on the future and a shift from focusing on the problem to focusing on the solution. As we have noted in other newsletters, late-stage buyers need reassurance. One powerful method of providing this reassurance is to gain increasingly larger commitments from the buyer.

Commitment (to help individuals move from Stage 3 to Stage 4 to Stage 5)

Commitment is the process by which individuals affirm their intent to act. This affirmation can take many forms, including nonverbal. For example, setting goals, forming action plans, and establishing timelines are all affirmations that there is intent to take action.

Commitment is not only evidence that there is intent to act; it can be a powerful motivational tool in and of itself. In his book, Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion Robert Cialdini states “Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment. These pressures will cause us to respond in ways that justify our earlier decision.”

The desire to behave consistently can encourage buyers to justify previous purchases with a later, larger purchase. In sales, this is known as the “foot in the door” technique – closing a small purchase as a means of facilitating and encouraging a larger one. This notion of escalating commitments is applicable to more than just purchases themselves, however. Verbal commitments are more powerful than commitments that are just thoughts, and written commitments are more powerful than verbal ones. As Cialdini states, “… the more efforts that goes into a commitment, the greater is its ability to influence the attitudes of the person who made it.”

Buyers in Stage 3 need reassurance and oddly enough, their previous behavior can supply this very reassurance. There is pressure to bring one’s self image into line with previous actions or risk the appearance of inconsistency. “If I said I would do this, then I have to, or I’ll appear to be inconsistent.”

Obtaining even small commitments from buyers can help influence future behavior. Examples of commitment include, among others: helping prospects set a timeframe for action, create a plan for the future, and set goals. Even offering buyers alternate choices can be valuable, as research has shown that those who are offered three choices exhibit greater commitment than those offered only two, or one.

Helping prospects move from Stage 4 Action to Stage 5 Maintenance

In Stage 4 Action, the prospect is actually ready to make a purchase decision. All the methods listed below are actually methods that facilitate closing the sale. Since salespeople close most large-ticket purchases in the life science sector, the methods listed below are frequently more relevant for sales efforts than they are for marketing efforts.

Stage 4 is the busiest stage; prospects are seeking information, refining and implementing plans, and actively addressing the issues and questions that arise. There are several methods for helping prospects finalize their decision. If they have reached this point, the planning stage has been passed. Often, what is needed is reassurance that the contemplated purchase is the right decision.

Reward (to help individuals move from Stage 4 to Stage 5)

Reward is the process of providing positive reinforcement for behavioral change. Rewards can take many forms. It does not have to be a physical item or have monetary value. Praise and encouragement can be used to facilitate change.

In a well-balanced change effort, rewards come third.Reward is a tricky subject. Most of us have heard stories of rewards that backfired, and those of us with children know that rewards can sometimes be de-motivating. In the book Influencer, the Power to Change Anything[ii], the authors state: “In a well-balanced change effort, rewards come third. Influence masters first ensure that vital behaviors connect to intrinsic satisfaction. Next they line up social support. They double-check both of these areas before they finally choose extrinsic rewards to motivate behavior. If you don’t follow this careful order, you’re likely to be disappointed.”

The book goes on to give a few tips for ensuring that rewards are used wisely. “Take care to ensure that the rewards comes soon, are gratifying, and are clearly tied to vital behaviors.” Frequently, it is the thought behind a reward that will carry the real weight, not the reward itself. Rewards convey social significance that can outweigh the face value of the reward; less can be more. Also, focus less on rewarding outcomes and more on rewarding behaviors, and your rewards will be more effective.

Given these caveats, rewards can motivate behavior. Common examples of reward include techniques like free shipping, discounts for purchasing multiple items, money-back guarantees and coupons; these can help tip the scales in favor of a purchase. However, rewards must be handled carefully, as some companies are so sensitive to the appearance of impropriety that they mandate the maximum value of gifts or other benefits.

Countering (to help individuals move from Stage 4 to Stage 5)

Countering – also known as substitution – is the process by which individuals substitute new (good) behavior for previous (poor) behavior. One example of this is the trial period: “We’ll give you a machine for a month, and you can try it out for free.”

When the purchase decision is a significant one, the decision can be broken into a series of small steps. Substitution can make it easier for a buyer to take one step at a time, substituting new behavior for previous behavior. In this scenario, Countering and a previous method, Commitment, are related. Breaking down one large step into a series of small ones is both an example of Countering – that is, substituting good (new) behaviors for old – and also an example of getting a series of small commitments from a prospect on the way to a larger decision (Commitment).

Not all decisions need to be broken down in this way, however, and the method of substituting one behavior (or set of behaviors) for another is distinct from that of gaining incremental commitments from prospects.

Another example of Countering is a phased engagement: “Our service normally involves these four phases. We’re not asking for you to buy all four at this time; start with the first phase, and then you can decide on the other three.” A technical audit/site visit is another Countering example during which a prospect gains first-hand experience with a new set of behaviors: “Oh, so now that I’m here, I can understand many reasons why it would be better to work with your lab than with my current provider.”

Environment control (to help individuals move from Stage 4 to Stage 5)

Environment control is based upon the recognition that a new environment can stimulate change. Yet, many of us are almost blind to the effect that our environment has upon us. Kerry Patterson et al. state: “Consequently, one of our most powerful sources of influence (the physical environment) is often the least used because it’s the least noticeable.” The authors go on: “…even when we do think about the impact the environment is having on us, we rarely know what to do about it.”

One of our most powerful sources of influence is the physical environment. This is often the least used because it’s the least noticed.Even so, the use of environmental control can assist in the marketing and sales of life science equipment and services. Examples abound: the site visit mentioned under countering above is also an example of environment control, where an opportunity for a closer look at the facility by the prospect can reassure them. Another example is showing a prospect how a lab would look with a new machine installed. Spatial audits and workflow analyses can also help prospects recognize the inefficiencies designed into current workspaces.

Helping relationships (to help individuals move from Stage 4 to Stage 5)

Helping relationships are defined as relationships that help the client buy, and buy again. There are enough intricacies in discussing helping relationships that we could fill a year’s worth of newsletters; I will only include one here: the one that Robert Cialdini calls Liking. He states: “…as a rule, we most prefer to say yes to the requests of someone we know and like.”

Besides your salesperson, others can be enlisted to assist in the process of facilitating the sale. References are a prime example of this type of helping relationship, but inside sales people and those who the prospect might talk to about post-sale issues, such as project managers, service technicians, among others, are also good examples of helping relationships.

The model is not the reality

The nine methods listed here cover a lot of ground. From the examples given with each method, I hope it is clear that these nine methods can be seen as nine categories of tools and techniques useful for helping individuals move from one stage in the buying process to another. But there is an old saying: “The map is not the terrain.” This is particularly true when discussing models of human behavior. Remember that the methods listed here are not static, foolproof, or universally effective. We are dealing with individuals, after all.

The techniques we have discussed are not always clear-cut, either. Some techniques illustrate multiple methods. For example, a testimonial could be an example of social liberation (“Oh, other people are exhibiting this behavior; it must be OK for me to do so, too.”) or an example of emotional arousal (“Boy, they sure sound relieved that their problem has been solved; I’m envious.”) or both.

This model of buying behavior can open up new ways of thinking about how to approach prospects at each stage – insights that can inform and enhance your marketing efforts.Even with these limitations, the model is useful in that it points out some interesting ways to help prospects progress down the path of change towards purchase. And it can open up new ways of thinking about how to approach prospects at each stage – insights that can inform and enhance your marketing efforts.

Summary

The transtheoretical model outlines the six stages that buyers go through as they progress through the buying cycle. The model posits that if you want to affect people’s purchasing behavior, you must identify the stage of change that they currently occupy, and provide the support appropriate to their needs at that stage. Providing support that is appropriate to the individual’s stage can increase the number of individuals who eventually end up ready to take action – that is, to buy. The model outlines the different methods that can be used to assist individuals as they progress through the steps in the buying process.

There are six stages of change through which buyers progress. To affect people’s purchasing behavior, you have to know what stage they are in. The support mechanisms effective for one stage might not be effective at other stages. This diagram describes the six stages and the nine different methods of inspiring change that are most effective for each stage.

[i] Cialdini, Robert B., PhD, Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion, New York, HarperCollins, 1984, 1994, 2007.

[ii] Patterson, Kerry; Grenny, Joseph; Maxfield, David; McMillan, Ron; Switzler, Al, Influencer, the Power to Change Anything, New York, McGraw-Hill, 2008.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.