The Power of Tone of Voice in Life Science Marketing – Part 3

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 11

, NUMER 4

Tone of voice is a powerful tool for differentiating your life science offerings. In the previous issue, I presented a new system for defining tone of voice: archetypes. In this third issue on tone of voice in life science marketing, I discuss the different components of tone of voice, and reveal the results of experiments done to test the link between archetypal patterns and vocabulary.

Creating the proper tone of voice through the use of archetypes in life science marketing.

This is the third in a series of white papers discussing the use of tone of voice in life science marketing. Why am I spending so much time exploring tone of voice? It is an underutilized tool in the marketing toolkit. Tone of voice can augment your audience’s impression of differentiation, creating greater separation between you and your competitors.

I’m guessing that not every single one of your employees who posts on LinkedIn or who creates copy of any kind has great copywriting skills. Since content creation and dissemination has been democratized through the use of digital tools, we need a way to spread tone of voice consistently across the entire organization, including even (or especially) those employees whose copywriting skills are not in the upper quartile.

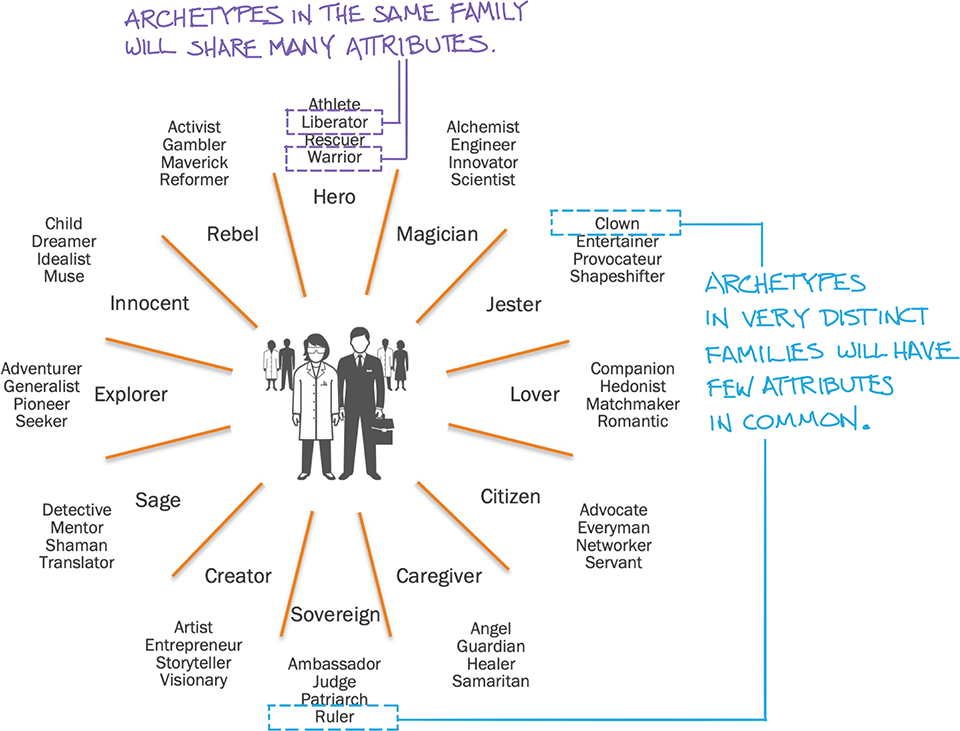

For this important task, archetypes are a powerful tool. As I discussed in the second issue, archetypes are patterns, embedded in our brains by our culture and society. These patterns contain many components, including labels and examples. The most important components are the attributes—behavioral attributes and character traits—including tone of voice. The tone of voice of one specific archetype (which represents a specific set of attributes) will be different than that of others. Jesters speak differently than Rulers; Heroes speak differently than Sages. By selecting an archetype and carefully defining the specifics of that archetype’s tone of voice, you can implement archetypes in a way that enables your tone to be defined clearly, controlled precisely and shared easily with others.

And again, if you control your tone of voice correctly—and consistently—you can augment your audience’s impression of differentiation.

Using archetypes to guide tone of voice.

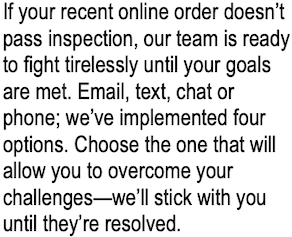

It’s fair to be skeptical about how well archetypes work. Can they really alter the impression of a viewer? I opened the last issue by discussing a research project that put this question to the test by comparing two different paragraphs. As a reminder, these paragraphs are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. The paragraph on the right was written using the tone of voice of a Warrior; that on the left embodied the tone of voice of a Caregiver. Can an audience perceive the difference between these two? The last white paper revealed the answer: Respondents perceived differences between these two paragraphs, and between the attributes of the two organizations that would write such paragraphs.

The paragraph on the left was written from the perspective of a Warrior archetype, which is associated with the following attributes, among others:

The other paragraph embodies the Caregiver archetype, which is associated with:

- a focus on you

- taking care of problems and issues

- altruism

As I discussed, respondents accurately discerned the difference between these two tones, and perceived different specific attributes related to each. Respondents found that the paragraph written from the perspective of the Warrior conveyed more “persistence,” while that written as a Caregiver conveyed more “taking care of you.”

In sum: readers discerned clear differences in these two paragraphs. They recognized the attributes inherent in each tone of voice, recognized the pattern of these attributes, and were able to identify which of the two additional attributes (“persistence” or “taking care of you”) would complete the pattern.

These readers attributed different behavioral attributes to the two organizations. Tone of voice helped differentiate the two.

The importance of controlling tone of voice.

The interesting fact about these two paragraphs is that there’s really very little difference between them. They’re both about the same length, and they have the same number of sentences. They both start with a qualifying sentence, letting the reader decide whether the rest of the paragraph is worth their attention. They follow that with a list of contact methods. And they both end with a call to action (i.e., if you’ve got an issue, please choose a contact method and get in touch).

If audiences are highly sensitive “tone detectors,” where do the signals they pick up about tone of voice come from?

Spoken language and tone of voice in life science marketing.

For marketing purposes, there’s a key distinction between harnessing tone of voice in written, as opposed to spoken, language. It’s intuitively easier to understand the sense of what someone is saying when you hear it (sarcastic, serious, angry, etc.) — it literally comes across in the “tone of voice.”

- content (what is said, including subject matter, etc.)

- visual (including facial expressions, hand gestures, posture, etc.)

- auditory (how it’s said, including vocal timbre, tone, emphasis)

- grammar and sentence structure

- vocabulary

That’s a lot to work with. Clearly, not all of these apply to written communication.

Written language and tone of voice in life science marketing.

What does tone of voice look like in written communications? Here the auditory and visual components are stripped away:

- content (what is said, including subject matter, etc.)

visual (including facial expressions, hand gestures, posture, etc.)auditory (how it’s said, including vocal timbre, tone, emphasis)- grammar and sentence structure

- vocabulary

Of those remaining components—content, writing style, and vocabulary—vocabulary is the easiest to control. Because it’s easiest to control, I’ve run many experiments to demonstrate vocabulary’s effect on readers’ perceptions.

How effective is vocabulary as a way to guide and control tone of voice? Can vocabulary by itself aid readers in distinguishing between two archetypes?

Is vocabulary a key component in an archetype’s pattern?

As seen in figure 2, we might expect the vocabulary of the Ruler to be more formal and respectful; the Clown would choose words that were more casual and irreverent.

Figure 2. We can use the spectra from the N/N Group to see the expected difference in the tone of voice used by the Ruler and the Clown, two common archetypes. While the spectra from the N/N Group are not necessarily great tools for guiding the creation of content with the correct tone of voice, I’m using them here because they are a nice visual way to reveal the stark differences between the different tones of voice for these two different archetypes.

All of this makes intuitive sense, but is it possible to “prove” this? The research I discuss above revealed that readers can discern differences between entire paragraphs. But what about individual words? Are there measurable differences between language that audiences would expect a Ruler to use, and that of a Clown? In other words, can we craft some research to demonstrate that vocabulary is a part of an archetype’s pattern?

Are there measurable differences in the vocabulary and tone of voice associated with different archetypes?

I’ve conducted several studies to answer questions like this. The next figure shows the results of one such project. I surveyed 100 adults in the US aged 18 and up. I gave them a list of six words (in random order) and asked two questions (again, in random order).

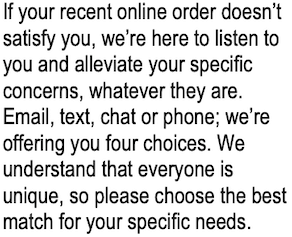

The results are shown in the following word clouds. Before you look at the results, how would you answer those questions. Which words would a Clown choose? A Ruler?

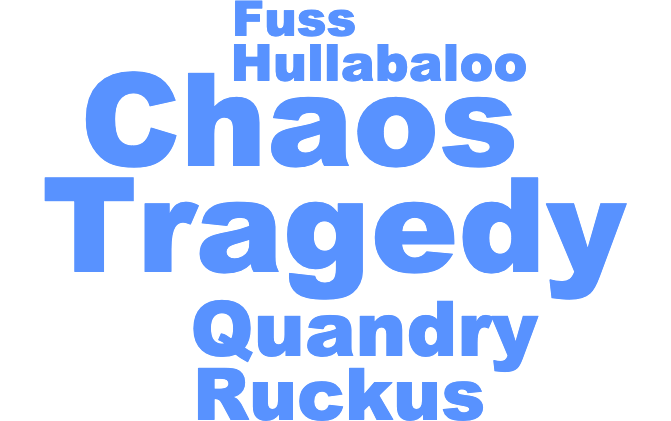

Figure 3: “Please select up to three words a Clown (or a Ruler) would use to describe a troublesome situation?” Answers for the Clown are shown on the left; the Ruler on the right. Note: the size of the words corresponds to the number of answers: a larger font size indicates more responses.

The results are clear: The Clown would be expected to use the words: Hullabaloo and Ruckus. The Ruler would be expected to use the words: Tragedy and Chaos. There is a clear difference between the words expected from two different archetypes: the Ruler and the Clown. This research shows that vocabulary is a key component of the pattern that makes up an archetype.

But what about unaided research?

The research I just discussed was “aided”—that is, I provided the respondents with a predetermined set of stimuli: a fixed list of words. To see if this result would hold with any stimuli, I also conducted a separate unaided research project. I surveyed 150 US adults aged 18 and up, asking two open-ended questions:

- What three words would a Jester use to describe a troublesome situation?

- What three words would a Sovereign use to describe a troublesome situation?

- “I don’t know” or “WTF?”

- nonsense answers (e.g., “Cup, dish, spoon”)

- political answers

- scatological references (after all, this is a family publication)

I adjusted some answers for clarity, for example, grouping “troublesome” and “trouble” together and counting them as conveying the same concept.

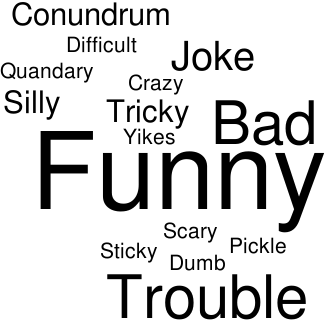

Figure 4: In a separate survey I asked two open-ended questions of US adults aged 18 and up: What three words would a Jester use to describe a troublesome situation? What three words would a Sovereign use to describe a troublesome situation? Jester answers are shown in the word cloud on the left; Sovereign on the right. The results shown here omit responses that were nonsense, political, or scatological in nature. I’m only showing answers that had a frequency of three or greater.

What do the data reveal? There are three words that show up on each list: Bad, Difficult, and Trouble. Among the remaining unique responses, there is a clear distinction between the two sets of answers. The words used by the Jester tend to be more colloquial, for example: Joke, Silly, Tricky, Crazy, and Pickle (as in, “I’m in a pickle.”). The words used by the Sovereign tend to be more formal, for example: Opportunity, Catastrophe, Disaster, and Difficult. In addition, the words used by the Jester tend to be shorter than those used by the Sovereign (5.8 vs 7.0 characters per word).

Some archetypes “blur” together. Some are more distinct.

It’s worth noting that the pairs of archetypes used in these two research projects (Jester/Sovereign and Clown/Ruler) were chosen to be very distinct. This choice was deliberate, to reveal as clearly as possible any patterns in the results.

One might say that these “familial archetypes” share enough similarities that they overlap—that is, they “blur” together. In the next issue, I’ll discuss the results of some research that reveal this type of blurring.

Figure 5. Across the 60 archetypes show here, and the thousands more besides, some share fewer similarities; some share more.

A three-part conclusion.

Part I

Archetypes are patterns we carry in our heads. There are thousands of these patterns, in all cultures. We can harness these patterns to help our messages resonate with audiences. As I’ll discuss in the next issue, displaying parts of the pattern in our public behavior conditions our audiences to want to “complete the pattern”—to look for additional parts of the pattern.

Part II

These archetypal patterns consist, in large part, of behavioral attributes. Communication style is one behavioral attribute; it is built from content, writing style and vocabulary. Of these three, vocabulary is the easiest to control.

Vocabulary is a significant part of an archetype’s pattern. Different archetypes are expected to use different words.

Audiences perceive differences in tone of voice in written communications. That is, audiences are tone detectors. They associate different behaviors and characteristics with different tones of voice. You can color the impressions your audiences have of you simply by using a specific tone of voice.

Archetypal patterns are defined in part by their vocabulary. These patterns live inside all of us. Research results show that audiences can quickly recognize these patterns. As we’ll see next time, there are several components that help our audiences recognize the larger pattern. As I hope is clear, tone of voice and vocabulary are two very important components that telegraph these patterns to our audiences.

Of course, for your audiences to recognize a particular tone of voice, they have to see it applied uniformly in everything of yours they read. Which means that if you’re going to add tone of voice to your arsenal of marketing tools, you’ve got to be consistent. That’s the topic for my next issue.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.