Using Two Dimensions of Positioning to Create a Competitive Advantage in the Life Sciences

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 10

, NUMER 7

Positioning is one of the foundations of effective marketing. Unfortunately, positioning is also one of the most confusing terms in marketing. (Except maybe “branding,” but that’s a topic for another issue.) And, as it turns out, when it comes to creating an effective marketing strategy for your life science organization, positioning is one of the easiest things to get wrong.

Using Two Dimensions of Positioning to Create a Competitive Advantage in the Life Sciences from Forma Life Science Marketing on Vimeo.

Positioning is one of the foundations of effective marketing. Unfortunately, positioning is also one of the most confusing terms in marketing. (Except maybe “branding,” but that’s a topic for another issue.) And, as it turns out, when it comes to creating an effective marketing strategy for your life science organization, positioning is one of the easiest things to get wrong.

How do I know? There’s lots of evidence, both subjective and objective. Let’s cover the objective evidence first: The thought leadership that gets the most traffic on Forma’s web site is—and has been for years—the content related to positioning. It’s not first by just a bit, it’s first by an order-of-magnitude blowout. People in the life sciences are hungry for content on positioning. Why? Probably for two reasons: the concept is poorly understood (that part is the theory) and it’s hard to do well (that’s the execution).

The subjective evidence comes from Forma’s three decades of working in the life sciences. Over all that time, we’ve seen very few organizations that have great positions. They do exist, but they’re few and far between. Admittedly there might be some confirmation bias at work here. We only get hired when firms are having trouble with marketing, so we tend to disproportionately see some of the worst marketing in the sector. But you have to remember that we also audit our clients’ competitors, and their positions are, in general, not much better. So I stand behind my statement: very few life science organizations have a strong position.

In this and some upcoming issues, I’m going to revisit positioning, and give you a few simple tools that can help you think about positioning in a new way.

There is only one reason for positioning—just one.

Choosing your position has only one purpose: to create a meaningful distinction between you (and your offering) and your competitors (and their offerings).

That’s it. Different—you have to be perceived as different.

If your offering is seen as meaningfully different, you can create a strong position—and you’ll be able to sell from a more favorable position, and have a chance to charge a price premium. If you’re not seen as different, you’re a commodity, and commodities have no pricing power.

Let me emphasize: This difference must be meaningful to your audiences—in other words, the difference must be a real differentiator. As I’ve written about elsewhere, we can tease apart “meaningful” into its component parts. Any real differentiator will be:

- important to the audience

- believable by the audience

- compelling to the audience

The classic example of a non-meaningful difference is a red-haired insurance salesperson. For people who want to buy insurance a salesperson’s red hair is a difference but not a differentiator, because it’s not important or compelling.

There are many definitions of positioning; few are helpful.

There are a couple of hundred definitions of positioning. And not very many of them are clear. Even Trout and Ries (who wrote the seminal article on positioning that ran in Advertising Age in the early 1970s and then wrote Positioning, the Battle for your Mind in 1981, from which I quote below) didn’t do a great job defining the term.

“Positioning starts with a product. A piece of merchandise, a service, a company, an institution, or even a person. Perhaps yourself.

But positioning is not what you do to a product. Positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect. That is, you position the product in the mind of the prospect.”

That may be a clear description of your goal, but it’s not a clear definition of positioning.

What is positioning?

In chapter 7 of my book Making the Complex Compelling, I defined positioning as follows.

Positioning is your organization’s conscious effort to select attributes that you want your audiences to associate exclusively with your offering.

The end result? A clear definition of these attributes. But you’ll need more than just these attributes. Even my own definition leaves some room for interpretation, so let me clarify.

First, your audiences must be specified (unless you’re trying to sell something to everyone in the world). This modifies our definition of positioning to become:

Positioning is your organization’s conscious effort to select attributes that you want clearly-specified audiences to associate exclusively with your offering/organization.

This is more specific. And yet, there’s still one more thing missing: your audiences’ needs. Their hunger to satisfy these needs is the fuel which will drive your marketing and sales success. Including these needs leads us to the following definition:

Positioning is your organization’s conscious effort to select attributes that you want clearly-specified audiences, whose needs you have clearly defined, to associate exclusively with your offering/organization.

This sentence is pretty clunky, isn’t it? But that’s okay; it’s accurate and it puts the focus where it belongs: on the exclusive attributes that you choose to attach to your offering.

Now that we understand the importance of attributes, we can look at the two dimensions of positioning. If you master these, you can gain a competitive advantage in the market.

The two dimensions of positioning.

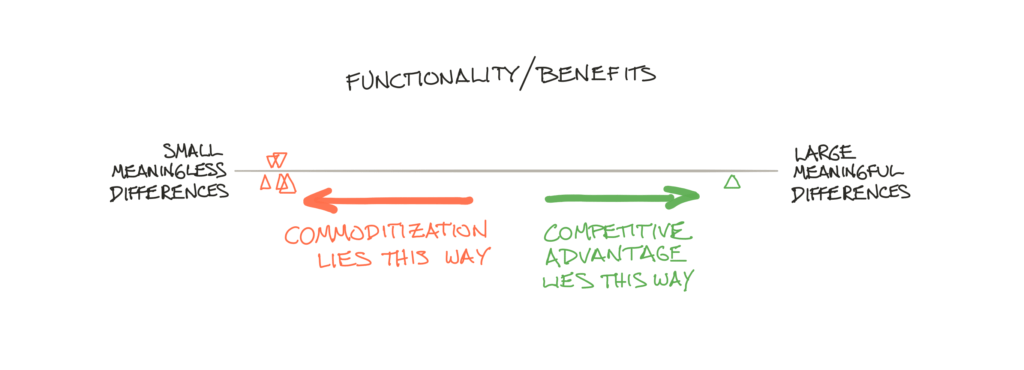

There are two fundamental ways that your attributes can be exclusive—that is, distinct from your competitors. The first axis of differentiation: your offering could have a significant difference in its functionality and benefits. If you have meaningful differences, you’ve got a competitive advantage. Without a meaningful difference, you’re a commodity, as seen in the following figure.

Figure 1. If there are meaningful differences between you and your competitors, you’ve got a competitive advantage. Without any difference, you’re a commodity.

Figure 1. If there are meaningful differences between you and your competitors, you’ve got a competitive advantage. Without any difference, you’re a commodity.

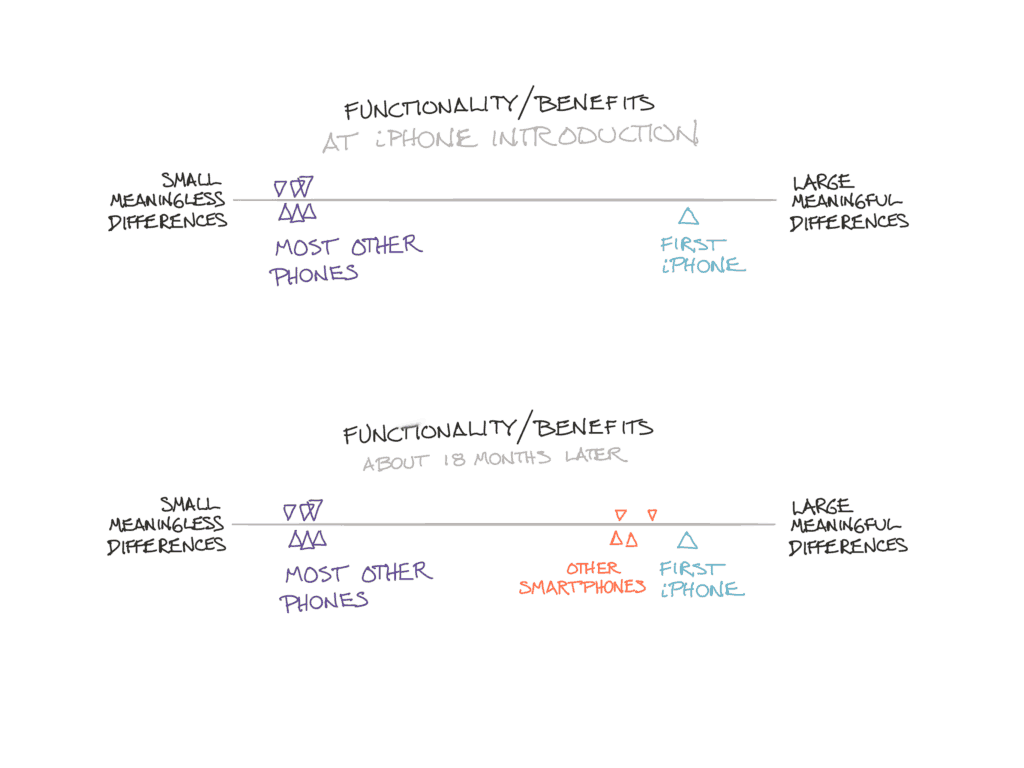

As an example, consider the iPhone, the very first smart phone introduced in 2007. Apple’s innovation created a phone that was meaningfully different from all other phones in functionality and benefits.

But this difference didn’t last too long, did it? Within 18 months, other smart phones started appearing, and the difference between the iPhone and competitors shrank dramatically. You can see this in figure 2, which charts the cell phone marketplace around the time of the first iPhone introduction. Figure 2: We can use a simple diagram to plot the differences between functionality/benefits from different competitors. If there is no difference, the offerings are in danger of being seen as commodities.

Figure 2: We can use a simple diagram to plot the differences between functionality/benefits from different competitors. If there is no difference, the offerings are in danger of being seen as commodities.

Countervailing pressures tend to homogenize markets over time.

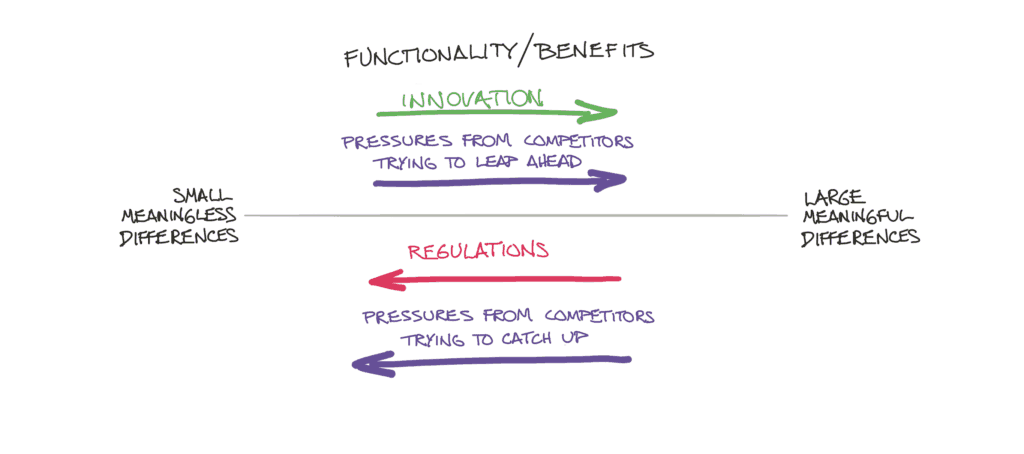

As the iPhone example shows, even a seemingly big difference can disappear quickly. There are only a few situations where dramatic differences in functionality and/or benefits last very long, because the world is so competitive. Businesses seek to extend this period of exclusivity in many ways, including, for example, regulation (e.g., patent protection), business strategy (e.g., reducing competition through the creation of duopolies/monopolies) and other ways.

But in the end, the overwhelming pressures of competitive innovation tend to reduce the situations in which clear feature/functionality advantages last very long.

At the risk of oversimplification, regulatory pressures tend to lower the difference between competitors’ offerings. Innovation tends to increase the difference. Competitive pressures tend to work both ways; attempts to “catch up” by competitors who are lagging behind tend to decrease the difference, while attempts to “leap ahead” by competitors who seek a competitive advantage tend to increase the difference.

Figure 3. Regulatory and competitive pressures from lagging firms tend to decrease the difference between firms’ offerings, while innovation and competitive pressures from firms seeking to leapfrog ahead of their competitors tend to increase the difference.

Figure 3. Regulatory and competitive pressures from lagging firms tend to decrease the difference between firms’ offerings, while innovation and competitive pressures from firms seeking to leapfrog ahead of their competitors tend to increase the difference.

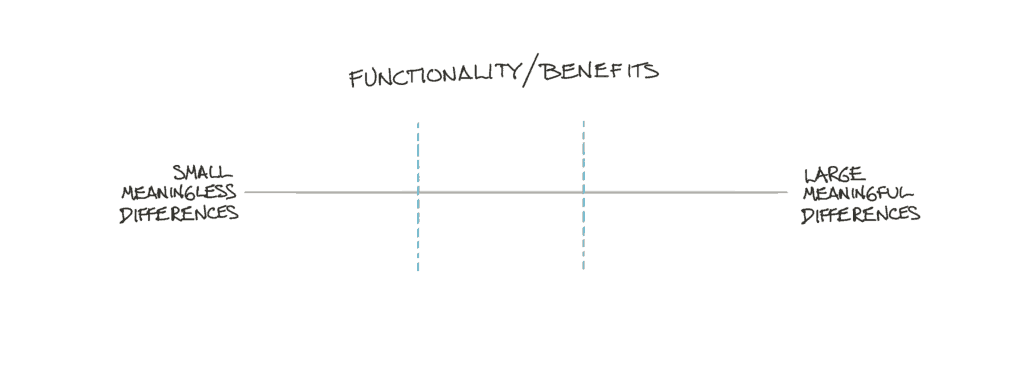

Where is your firm on this spectrum? That is, how large are the differences in functionality and benefits between your offerings and your competitors? Extremely large, extremely small, or somewhere in the middle?

Figure 4: Where does your firm fall, with respect to competitors? Are the differences between your offerings very large, somewhere in the middle, or very small?

Figure 4: Where does your firm fall, with respect to competitors? Are the differences between your offerings very large, somewhere in the middle, or very small?

As you answer, I don’t want you to place too much weight on minor differences in functionality; I’m talking about significant differences, ones that are Important, Believable, and Compelling. I predict that if you answer honestly, your score will fall somewhere on the left side of this spectrum. And I’d predict the same pattern would hold true for your competitors, too. Of course this pattern won’t be true in absolutely every case, but creating and maintaining unique functionality is hard. And it’s harder to maintain over time, because of competitive pressures.

In other words, among a given group of competitors, functionality/benefits tend to cluster together over time. Innovation will disrupt this “clustering” effect, but in regulated sectors, innovation can be difficult and slow.

Symptoms of trouble.

Now remember: If you’re not seen as meaningfully different, you’re seen as a commodity, with no pricing power. So if the differences between your offerings and your competitors’ offerings are small, then you’re in trouble. This trouble will manifest itself as a series of symptoms. You can view these as signs that you haven’t done a good job creating a differentiated position for your offering.

Price pressure. If you’re constantly under pressure to lower prices, your positioning is poor. Any perceived differences between you and your competitors aren’t enough to command a price premium. In other words, the buyers you’re selling to see your offering as just one of many acceptable substitutes. Ask yourself: How often do you face price pressure?

RFP. If you are forced to participate in flawed selection processes, then your positioning is poor. An RFP process is built on one fundamental idea: that the differences between the participants are so small that there must be an elaborate, in-depth comparison to bring these differences to the surface. (In all fairness, there can be some mitigating circumstances when discussing RFPs. For example, the value of some contracts is so large that corporate procedures mandate the use of an RFP process. But even in these circumstances, there have been times when buyers find a way around these requirements, because they see one seller as meaningfully different.) Ask yourself: How often are you forced to sell through the RFP process?

Language. If the buyers you’re trying to sell to speak of you as a “vendor,” then your positioning is poor. The use of the word “vendor” implies that the offerings are virtually indistinguishable; it typically describes someone who sells things such as newspapers, cigarettes or food from a small stall or cart, like a hot-dog vendor. The word “supplier” isn’t much better. Ask yourself: How often do your buyers refer to you and your competitors as vendors?

Okay, now what?

If you’re seeing these symptoms, how can you improve your competitive position? One classic answer is to respond with lower prices. But that’s a fool’s game, isn’t it? Only one firm will win that race to the bottom, and the cost of doing so can be high.

There is another way to compete. It comes from competing on additional dimensions—beyond just functionality/benefits. You don’t have to look far to see some successful examples of this. The world is full of products and services that aren’t that differentiated by their functionality/benefits: laundry detergent, soft drinks, and fast food chicken sandwiches, to name just a few.

These offerings come from organizations that are some of the world’s best at marketing. How do they compete? How do they create a difference in consumers’ minds? They create differentiation through their articulation—that is, their appearance and tone of voice. Some people call this a “brand,” but I hate that word, because there are so many conflicting definitions. But no matter whether it’s called “brand,” “articulation,” or something else, this is often the only distinction between products and services that aren’t otherwise differentiated.

Differentiating using articulation.

If you’re familiar with Chick-fil-A®, you know an organization that is using their articulation to distinguish themselves from their competitors. Is Chick-fil-A’s chicken sandwich different from other major fast food chains? Yes, it is, though only in minor ways. McDonalds’® chicken sandwich lists something called “Signature Sauce” in their ingredient list on their web site; Chick-fil-A lists no such sauce.

But when you think about the difference between Chick-Fil-A and McDonalds, I doubt you put much focus on the sauce. Instead you’re likely thinking about Chick-fil-A’s clumsy inventive cows. In other words, you’re thinking about how Chick-fil-A articulates their message, rather than the message itself.

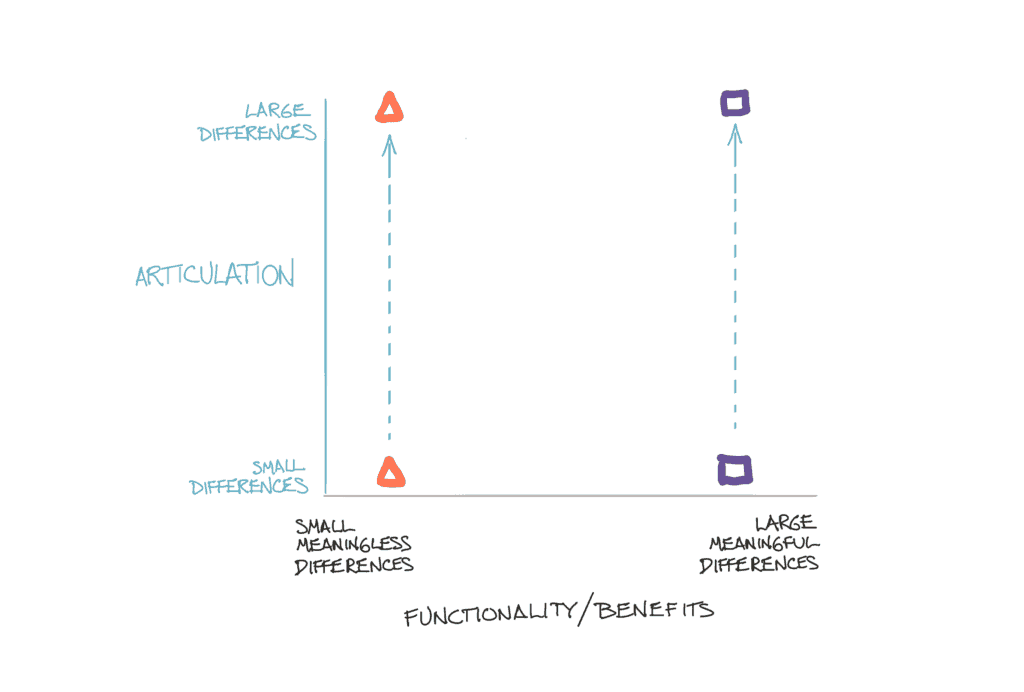

You see, tone of voice and appearance represent the second dimension of competitiveness, a dimension we can use to create a differentiated position, as in figure 5.

Figure 5. If your offering is not strongly differentiated, you can improve your competitive position by differentiating your tone of voice and your appearance. If your offering is strongly differentiated, you can still improve your competitive position by differentiating your tone of voice and your appearance. It works in both situations. Using another dimension can help you create a (more) differentiated position.

Figure 5. If your offering is not strongly differentiated, you can improve your competitive position by differentiating your tone of voice and your appearance. If your offering is strongly differentiated, you can still improve your competitive position by differentiating your tone of voice and your appearance. It works in both situations. Using another dimension can help you create a (more) differentiated position.

Comparing the two dimensions.

Within the world of marketing, there are countless examples, across many industries, of how both dimensions can be used to create differentiation. But for technically trained audiences—that is, for most audiences in the life sciences—a desire for data and proof biases them towards a belief that the only difference that matters is functionality/benefits. In other words, these audiences often believe that the horizontal axis in my diagram is somehow the only axis that matters. There’s nothing wrong with differentiating your offering by proving you’ve got superior functionality or benefits, if such proof exists. But as I’ve already discussed, many life science offerings don’t deliver much difference on the horizontal axis.

It’s possible to prove that the second axis—articulation—is every bit as powerful a differentiator as the first one. To gather that proof, we have to do perception research with prospects. To make the results statistically significant, we have to get input from lots and lots of respondents, so that proof tends to be expensive.

Since most life science organizations don’t have huge marketing budgets, they tend to forego this type of expense. This reinforces the bias: “I haven’t seen any data that the second axis works, so the first axis must be all there is.”

This is a blind spot.

But here’s a secret. If competing by differentiating through articulation is undervalued by many people in the life sciences, it stands to reason that this is probably undervalued by many of your competitors. Which means that we can use their blind spot against them.

I’m not suggesting that you should only compete on one axis or another. By all means, use everything you’ve got. If you’ve got meaningful differentiators on the functionality/benefit axis, congratulations. You can augment those differences by competing on the articulation axis.

All the proof you need.

How do you maximize your competitive advantage through your articulation? The world is full of successful companies who make great profits competing primarily on the articulation axis. It would be stupid to ignore the possible benefits of doing so.

In a future issue, you’ll learn from these companies, as I outline what it takes to bolster your positioning using the articulation axis.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.