How to write an effective life science case study Part 2: Let go of the details

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 9

, NUMER 5

Your life science case study can work wonders: it can inspire or reassure prospects who are on the path to purchasing your products or services. But it must be well designed—the right length, the right amount of detail, the right contents and the right structure. Many organizations use their peer-reviewed journal articles as a substitute for their case studies. This is a bad decision with disastrous consequences, and I'll explore why in this issue.

To write an effective life science case study, let go of the details.

In the last issue, I began exploring the topic of an effective life science case study. An effective life science case study can serve several functions as your prospects traverse the buyer’s journey. It can provide inspiration, which your early-stage prospects need to help them decide that their life could really be better—that they have a problem in need of solving. It can also provide reassurance, which is what your late-stage prospects need as they approach the end of the buyer’s journey.

Effective life science case studies can accomplish many things. They can create a lasting impression in a prospect’s mind. They can augment your reputation and build name recognition. Effective case studies can reveal the details of a specific engagement, and allow the prospect to envision themselves as part of a story with a successful conclusion. If they need formulation work done and they’re reading a life science case study about formulation, it’s easy for them to see themselves and their problems.

Effective life science case studies reassure our audiences that we can handle their challenges. It builds trust by revealing our process. Even more important, it reveals that our process is an important part of our offering.

And most important of all, effective case studies articulate your unique value proposition and your carefully chosen marketing position, which reinforces the differentiation between you and your competitors.

I’ve been talking a lot about “effective” life science case studies. There are many case studies that are not effective.

Your prestigious journal article is not an effective life science case study

From my long experience in B2B life science marketing, it’s clear that many organizations believe that they’ve already got great case studies: their peer-reviewed journal articles (which I’ll refer to by the acronym PRJA). In fact, many web sites actually have sections entitled “Case Studies” that are populated solely with PRJAs.

I can just imagine the thinking that supported this decision. “Hey, it took a lot of time and effort to run this experiment, and write it up, and respond to the reviewers. This proves we can do some serious science. After all, haven’t these articles been validated by some of the best minds in the discipline (the peer reviewers) and published in the most prestigious journals? And this is the best representation of what we’ve done, down to the smallest detail. What more could a shopper want?” And then someone else in the room adds, “Plus, they’re already done. It’s like we’re getting ’three-for-one’ because we got the client to pay us to do this work, and then we got a published article out of it, and now we can use it as a case study.”

I understand this logic, but I must frankly disagree: the typical PRJA makes a horrible case study. Why? There are a lot of reasons why a peer-reviewed journal article makes a lousy life science case study. Let’s take a closer look at the main ones.

A peer-reviewed journal article doesn’t include the key ingredient necessary in an effective life science case study

Let me start with a statement to put all of marketing—the entire discipline—into perspective. Everything your prospects see, every piece of content, everything on your website, every webinar, every possible marketing touchpoint they come in contact with, should reinforce one overall message: your carefully chosen marketing position. If you convey your position, anything else you achieve can be considered a bonus. If you don’t do this, you’re missing the point, and so will your prospects (and they’ll be less likely to become your customers).

Everything your prospect sees should reinforce one overall message: your carefully chosen marketing position

This is a bold statement, but it’s the truth that lies at the heart of all marketing tactics. If you don’t tell prospects through your marketing tactics how they should think about you, they’ll make up any old thing and carry that around in their head. You’ll be stuck with whatever label they happened to pick—or whatever label your competitors’ sales people implicitly or explicitly whisper in their ears. This is why consistency is so important. You must reinforce your messages over and over again, first to emphasize and cement and later to remind and defend.

With that in mind, let’s look more specifically at position-based messaging versus PRJAs. Assuming that your position has been validated (it has been, right?), we know it meets the seven basic criteria—namely, that your unique value is:

- clearly stated

- unique

- authentic

- sustainable

- important to the audience

- believable by the audience

- compelling to the audience

In this light, our case studies should highlight what separates us from our competitors: our position. PRJAs can highlight many things. They can highlight that you can do serious science. (But that shouldn’t be your position, because it’s not unique; lots of people do serious science.) They can highlight that you are an expert in a particular area of science. (“Look, nobody knows more about neonicotinoid toxicity than we do.”) But conveying that point requires more than a single PRJA, which by itself conveys not global knowledge about a topic, but very specific knowledge about one small section of that topic.

A PRJA takes a very, very narrow topic and makes a very, very narrow point about it. A peer-reviewed journal article does not include the key ingredient that makes an effective life science case study.

A peer-reviewed journal article has too many details to be an effective life science case study

A peer-reviewed journal article is supposed to be written so that any scientist anywhere could duplicate the experiment. This means, ideally, that it must cover each and every detail that could change the experiment. It’s not enough to say, “We added some reagent.” If the amount of reagent and the way it was added could substantially alter the results of the experiment, the paper must specify how much reagent was added, when it was added, how it was added, the mixing that occurred, etc., etc. Sometimes this detail lives in a supplemental appendix, but it’s always supposed to be there.

This detail is necessary if we’re trying to teach someone how to duplicate the experiment, which is one of the purposes of a PRJA. But that’s not the purpose of a life science case study.

A PRJA is a great vehicle for describing a specific experiment, and what it means. But it doesn’t make a good vehicle for describing your position in the marketplace. In fact, reviewers frown on the inclusion of any sales-focused information in a PRJA. In contrast, a life science case study exists to demonstrate something else. In essence the case study exists to highlight what separates us from our competitors: our position. This might be how smart, tenacious, insightful or experienced we are, or something else entirely. But it will always be something important that we can convey without specifying the titration rate of the reagent. All the detail included in a PRJA is unnecessary to get across the point we want to make.

A peer-reviewed journal article is too detailed to make an effective life science case study.

A peer-reviewed journal article is too long to be an effective life science case study

All the details we just talked about make a PRJA too long. The readers of our case studies are seeking the answers to a simple set of related questions: “Do they have the expertise to solve my problem, and if they do, should I begin (or continue) a conversation with them?”

I’ve written elsewhere that a scientist creating a peer-reviewed paper doesn’t care how long it takes a reader to read and understand a PRJA. Their main goal is not audience comprehension, or brevity, or communication effectiveness; it’s completeness and accuracy.

Because the focus is on being complete, a peer-reviewed journal article is too long to make an effective life science case study.

A peer-reviewed journal article is pitched at the wrong audience to be an effective life science case study

A PRJA is written for peers, so the author assumes significant scientific knowledge on the part of the audience. In contrast, a life science case study should be written for non-peers, readers who know less than you do about a particular subject. If you write a case study for that audience, you’ll also reach other audiences, including those who know as much as you do.

To explore this topic, let’s examine all the reasons that people might buy your service/product. Simplistically, we can divide the world into two groups:

- those who could do it all by themselves

- those that can’t

And we can further subdivide the first group into three:

- They have the expertise and ability to do what they might hire you to do, but they just don’t have the time or the resources (an issue of their capacity)

- They have some expertise and ability, but they can’t do the job as quickly (an issue of efficiency)

- They have some expertise and ability, but they can’t do the job as well (an issue of quality).

| Different audiences | An issue of… | Relevance of a PRJA to this audience | |

| 1 | Could do this by themselves | Very relevant | |

| 1a | But don’t have the time or resources | Their capacity | |

| 1b | But can’t do the job as quickly | Their efficiency | |

| 1c | But can’t do the job as well | Their quality | |

| 2 | Could not do this by themselves | Their ability | Not very relevant |

Figure 1: PRJAs are most relevant to those who are your peers, those who could do what you do. But they’re the ones who are least likely to hire you. A PRJA is pitched at the wrong audience to be effective as a case study.

A PRJA is only really relevant to audiences at the very top of this diagram; they’re the only ones who can completely understand it. Many of the other audiences don’t know as much as you, so they need your help. A PRJA, with its focus on details and completeness, can easily overwhelm these audiences.

Needless to say, you don’t want to overwhelm them. You want to help your audiences answer the questions they are asking themselves, the ones I referred to earlier: “Does this potential partner have the expertise to solve my problem, and if they do, should I begin (or continue) a conversation with them?”

You want to inspire or reassure these audiences. You definitely want to impress them. So you should write for people who don’t know as much as you do about the process required to get something done. And you should write for people who are very interested in the benefits that result from its successful completion. A peer-reviewed journal article is pitched at the wrong audience to be an effective life science case study.

A peer-reviewed journal article is focused on the wrong topic to be an effective life science case study

The basic structure of a PRJA is simple: Question, Methods, Results, Discussion. “Here’s the question we wanted to answer. Here are the methods we used. Here are the results we got. Here is what this means.” That’s a PRJA in condensed form.

Question, Methods, Results, Discussion. The first section (the all-important question) is the driving force behind the PRJA. And the last section, the discussion, is where the all-important answer and the meaning of the answer are revealed.

| Peer-reviewed Journal Article | |

| Introduction (Including the all-important Question) | This Question is the driving force behind the PRJA |

| Methods | |

| Results | |

| Discussion (In which the all-important Answer is revealed) | This answers the initial question and provides meaning. |

Figure 2: The standard story that a peer-reviewed journal article tells follows a clear pattern. The focus is on the question and the resulting answer.

Of these four sections, the two most important are the first and the last: the Question and the Answer. But these aren’t very useful from a marketing perspective, so this focus on Question→Answer is the wrong focus for a life science case study.

I love peer-reviewed journal articles

Lest you think that I hate PRJAs, let me put your mind to rest. A PRJA is great at teaching other scientists how to duplicate an experiment. And even though this duplication of effort happens very rarely, PRJAs are a great way to help the scientific community transfer methods from one scientist to another. For service companies in the life sciences, such as CMOS, or analytical labs, or organizations that do formulation or toxicology, PRJAs do demonstrate that you can do good science. Once you get used to reading them, it’s fairly easy to tell the difference between shoddy work and iron-clad thinking in a PRJA.

The point to remember is that while PRJAs demonstrate that you can do good science, this is not as valuable from a marketing standpoint as you might think. For one thing, “we do science really well” doesn’t work as a unique valuable proposition. Doing science really well isn’t completely unique, and all of your competitors will claim that they do science really well. So this claim is not unique. And, for those of you who have been playing along at home, uniqueness is one of the seven cardinal requirements for a position.

All of this raises the obvious question: what is the correct focus for a life science case study?

What is the focus of most case studies?

As I’ve been writing this series of white papers I’ve reviewed scores—if not hundreds—of life science case studies, and I’ve noticed some patterns among the good ones and the bad ones. The bad case studies fall into a couple of different classes. In the first class are the mini-peer-reviewed-journal-articles, which look just like a PRJA (but without the peer-review). The case studies that fall into this class lack a prestigious journal title on the first page, but otherwise they’re similar to a typical PRJA: they have the same structure, the same extremely narrow subject, the same detail-overload, the same length (too long, but not as long as a typical PRJA), and they’re focused on the wrong topic. In the focus on Question & Answer, they miss the main point that they should be making.

The second class of bad case studies contains those that are a collection of facts, typically presented as a list of bullet points. Here’s one sample pulled from the website of a well-known organization. To “protect the innocent” and preserve this organization’s anonymity, I’ve changed some of the minor details.

Manufacturing Case study

- Worked with customer from early phase clinical through commercial scale-up

- Implemented temperature-controlled extrusion methodology

- Implemented aseptic drug loading and fill and finish

- Developed process using stainless steel jacketed mixing system

- Using disposable reactor, successfully scaled up the process for commercial manufacturing, minimizing operational costs and maximizing robustness

- Validated novel system to preserve aseptic integrity

- Validated cleaning procedure of highly-potent compound

- Customized a just-in-time final visual inspection to minimize degradation prior to final frozen storage.

That’s it, that’s the case study. Are you intrigued? Do their unique capabilities come shining through? Are you motivated to act? Me neither. This dry recitation of facts and steps doesn’t help.

Are there any goals listed? No goals are ever stated directly. The reader doesn’t even understand that this might be a difficult challenge till the penultimate bullet point, when it’s revealed that this is a “highly-potent” compound.

Are there benefits there? Yes, there is a passing glance at some benefits, such as “minimizing operational costs and maximizing robustness.” But these aren’t outlined at the beginning, so the reader isn’t sure whether these were just a lucky accident, or the overall focus of the entire program.

Can you tell if this organization is doing anything their competitors might not be able to accomplish? In other words, is there any uniqueness? Not really. Through the use of the words “novel” and “customized” the reader is given a few hints that this organization had to develop some innovative solutions to get around difficult challenges. But this isn’t emphasized.

Is there a flow to this story? Do they start with a “big grabber,” something that intrigues the audience? No. There is very little attempt to engage the reader, to tantalize them so that they want to “see how it ends.”

If your case studies don’t outline the goals of your efforts, then how will the reader know if you were successful? If your case studies don’t reveal the benefits that customers can receive, then why would they ever become a customer? If your case studies don’t highlight your uniqueness, aren’t you positioning yourself as a commodity? If your case studies don’t engage your readers, how will you get them to stick with you to the end?

Benefits, goals and uniqueness must all be obvious to your reader. If you make the prospect work too hard to see it, you’ve already lost them. You can’t be afraid to be obvious.

No benefits, no goals, no uniqueness, no engagement—without these there can be no impact.

Your life science case studies should focus on the combination of your approach and your value

This series of white papers (which I’ve been writing since 2008) has a broad focus: I want to cover marketing that’s relevant to all the different types of life science organizations. For example, service organizations in the life sciences include clinical research organizations, contract manufacturing organizations, analytical labs, biostatisticians, toxicologists, clean room services, supply chain and logistics, etc.

I must also include the organizations that supply scientific and medical products, such as disposables, reagents, scientific instruments, diagnostic tools, laboratory equipment, medical devices, etc. And I can’t omit consultants of all types.

That’s a lot of different types of organizations. And these organizations face different types of challenges, with different solutions. The spread is so wide that it’s difficult to specify what will work for each and every case study.

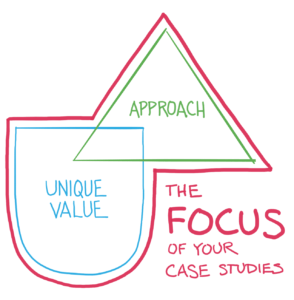

What should be the focus of your life science case study? The poor examples that I cite provide evidence of what not to do, and thereby help shine a light on what you should do. They point the way to an effective case study: one that is meaningful and potent. At the risk of overgeneralizing, the focus of your life science case study should be a balance of your unique value and your approach. In other words, you want to highlight both how you helped your customer (that is, your process or your approach) and your unique value (and the subsequent benefits of choosing you, your products or your services). These two must have equal weight.

This sounds simple, doesn’t it? Judging from the existing evidence (all the poor case studies out there), it’s surprisingly difficult to do.

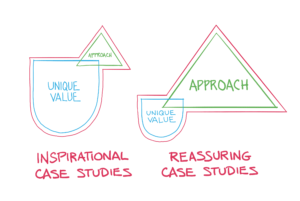

Figure 3: The focus of your life science case study should be to present a balanced picture of your unique value and your approach.

I use the word “approach” deliberately, because I’m writing for all different types of life science organizations. It should be clear to service companies and consultants what I mean by the word “approach.” Simply put, your “approach” is your process or your methodology for meeting the challenges faced by your customers. This should be presented to be as unique as possible. Of course, creating and demonstrating a completely unique approach will be difficult in some regulated sectors of the life sciences, such as contract manufacturing. But even in these cases, your tone of voice and the articulation of your approach can be positioned to be different. This is one place where archetypes would be applied to the creation of your case studies, as archetypes help you articulate your messages in a consistent and differentiated manner.

For companies that make products, the word “approach” must be broadened beyond the very literal definition (“methodology”) that I just referred to. In this case, your “approach” might refer to the trade-offs and other choices your engineering and marketing teams made when creating the instrument. This language might sound like: “In order to maximize both sensitivity and accuracy, we went back to the drawing board and developed an entirely new sensor array, one around which we built our new instrument.” Or your “approach” might refer to the vision you have for the sector: “We want to enable every researcher everywhere to have access to the latest technology at an affordable price. That’s why we simplified one of the most expensive components of our newest instrument, the washing chamber.”

Whether you work for a service company or a product company, a focus on approach will help your readers envision themselves as part of the story, and see how they could take advantage of your offerings—one of the prime purposes of your case studies.

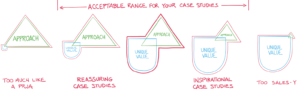

Be careful about getting out of balance

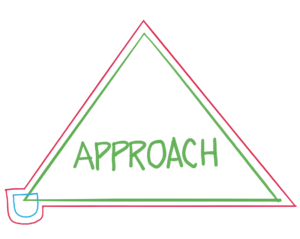

If you put too much focus on methodology, you won’t cover the unique value you bring or the benefits you offer. (Now it should be clear why a PRJA doesn’t make an effective life science case study: They put too much emphasis on methodology and not enough on unique value.)

Figure 4: Overwhelming emphasis on your process (methodology) detracts from your ability to highlight the benefits of choosing your solution.

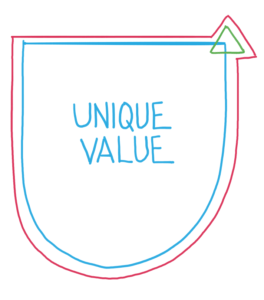

On the other hand, if you put too much focus on your unique value and too little focus on your approach, you won’t enable the reader to see themselves in the case study. With all this focus on you, your unique value, and the benefits you provide, you run the risk of coming across as too sales-y.

Figure 5: Overwhelming emphasis on your unique value feels too much like a sales pitch, and will impede your readers from seeing themselves and their situation in the story you’re telling.

Inspirational and reassuring case studies

In the last issue I covered the need to have two different kinds of effective life science case studies: inspirational case studies for those (early stage) buyers in stage 2 (Contemplation), and reassuring case studies for those (late stage) buyers in stage 3 (Planning) and 4 (Action). How does a focus on the intersection between Unique Value and Approach take form in these two very different kinds of case studies?

Let me be clear; the balance between Approach and Unique Value will shift depending upon which type of life science case study is being written.

Effective life science case studies enable the reader to envision a better life. To accomplish this, we need to draw attention to two things. Primarily: by putting more attention on our unique value, we highlight the benefits that are available through choosing our solution. These benefits can be very inspirational. Secondarily, by also giving some attention to our approach, we enable our readers to envision themselves as part a successful story like our case study. These types of case studies are particularly useful for early stage buyers, who are stuck in contemplation mode; shopping and shopping but not finding any solution that is inspirational enough to get them to act.

On the other hand, effective reassuring case studies enable the reader to put their doubts to rest. To accomplish this, we again need to draw attention to two things—but now the emphasis has shifted. First, we put more attention on our approach, so that we reassure our readers that we’ve done all of this before, and they’ll be in great hands. This focus on approach can be very reassuring. Second, by also paying some attention to our unique value, we remind our readers that the benefits we offer are not available from any other supplier. These types of case studies are particularly useful for late stage buyers who are actively planning to act; they tend to worry that they’re going to make a mistake.

The difference between inspirational and reassuring case studies can be seen in the following figure.

Figure 6: Inspirational and reassuring life science case studies will have a slightly different balance. Inspirational case studies will emphasize unique value (the major focus) more than approach (the minor focus). Reassuring case studies will emphasize approach (the major focus) more than unique value (the minor focus). But in both cases the minor focus still plays a significant role, unlike in figures 4 and 5, above.

It’s important to note that the difference between these two is very subtle. We don’t want to overemphasize one facet (such as your unique value) at the expense of the other (your approach).

Figure 7: The entire spectrum of possible effective life science case studies is shown here. Avoid either end of the spectrum, that is, avoid overemphasizing either your approach or your unique value.

Summary

Your life science case studies can be incredibly effective tools of inspiration (for early stage buyers) and reassurance (for late stage buyers). Many life science organizations believe that their peer-reviewed journal articles make effective life science case studies. This is false. PRJAs are wonderful tools for spreading scientific knowledge, but they have many flaws when they are used in place of effective life science case studies. They make the wrong point. They are too detailed. They are too long and they focus on the wrong audience. Most important, they are focused on the wrong topic: QuestionàAnswer. In contrast, an effective life science case study balances your approach and your unique value.

How do we translate that very specific balance into an effective life science case study? That will be the topic I explore in my next issue.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.