How to write an effective life science case study: Inspire and reassure your prospects with life science case studies

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 9

, NUMER 4

The life science case study is an often-overlooked tool in life science marketing. Life science case studies can be a powerful way to inspire or reassure your audiences, helping them at specific points in the buyer’s journey. I’ve looked at lots of case studies: CRO case studies, biotech case studies, pharma case studies, analytical lab case studies; the list goes on and on. And what I’ve learned is that too many life science sales and marketing teams waste the opportunity to maximize the impact of this simple but effective tool. In the first of a series of whitepapers, I peel apart the use of life science case studies and reveal the multiple benefits they offer. I’ll discuss the two different types of case studies and show how the focus of each is very different. In future issues, I’ll reveal how to build the most effective (non-boring) life science case studies.

The journey your prospects take to a closed deal in life science sales and marketing can be improved with a life science case study

There are many steps on the journey to a closed sale. Here are just a few that your prospect might take:

- deciding that the challenge they’re facing is significant enough that they need to seek a solution

- looking for solutions by using a search engine

- visiting your website (anonymously)

- deciding your capabilities are a match for their needs

- raising their hand (dropping their anonymity) to begin a conversation

- asking for a capabilities presentation or more information

- giving you an RFP

- asking you to attend a bid defense

- negotiating the final details of the contract

- signing the final contract

Of course, as they say in the automobile ads, “individual mileage may vary.” Every prospect is different and the journey to a signed contract never follows the exact same steps. There are dozens of major and minor decisions that are made along the way. But no matter how each individual journey unfolds, there are two major decisions that your prospect must make.

First, your prospect must decide that their pain needs to be addressed. In other words, they’ve decided to do something about their problem. The first step in the bullet list above captures this idea: deciding that the challenge they’re facing is significant enough that they need to seek a solution, rather than accepting the status quo.

Second, they must qualify you. They gather enough information to decide that your products or services can indeed accomplish the job they need done. At this point you switch from being unqualified to qualified in their eyes. Once they qualify you, you pass a threshold. The conversation will shift in topic and tone; you’re seen as a potential partner who can help them with a current or future need.

How well do most life science organizations support these two very important decisions? Let’s take a look at the two main channels for this support: a web site and a capabilities presentation.

Oh, the websites we’ve seen in life science sales and marketing

As part of Forma’s standard diagnostic on-boarding process with new clients, we audit their websites. We’ve noticed a couple of common issues.

- Lack of a main point: the worst-performing websites lack a clear message or focus. Worst of all, they make no claim of unique value. It makes me wonder; do these organizations want to be seen as a commodity offering? If so, they’re doing a pretty good job.

- Improper focus: the worst-performing websites are focused on their own organizations. It’s all about “us” or “our company,” “our history,” “our locations” or “our equipment.” There is no room for the prospect to see themselves in the story (more on this later).

Oh, the capabilities presentations we’ve seen in life science sales and marketing

In addition to auditing websites, we ask each client to designate several members of their sales team to deliver a capabilities presentation. “Just pretend we’re a prospect,” we say. “Show us what you’d show them.”

Many poor performing websites and sales presentations have the wrong focus; they don’t allow the prospect to see their problems being solved.

What we’ve seen over the years has been remarkably consistent. Unfortunately, it’s been consistently poor. In fairness, from the salespeople’s points of view, these presentations don’t count as “real games;” they’re just “no-contact scrimmages.” So it’s not surprising that they don’t have their game face on. But even so, I’d expect these salespeople to put forth a higher level of performance than they do, if only because their boss might ask me how they did.

Our team always debriefs after these encounters, and the notes we share typically fall into several categories.

- Lack of consistency: individual sales people on the worst-performing teams deliver presentations that are significantly different from each other. I’m not talking about differences in individual personality and style; we make allowances for those differences in delivery. I’m really referring to inconsistency in content. We’ve seen presentations that use completely different slide decks, in some cases with completely different background images and formats. In a few cases, each presenter will, when questioned, maintain that they’re using the one, approved presentation deck—which can’t be true because the decks are drastically different. (Okay, maybe they were identical at one point in the distant past, before each sales person just made “a few tweaks here and there” for each new prospect and the content naturally evolved. Or devolved.) Whatever the cause, the result is a mess: prospects are getting presentations from what look like completely different companies, with completely different claims.

- Lack of a main point: the sales presentations from the worst-performing teams lack a clear message or focus. They wander from topic to topic. Worst of all, they make no claim of unique value.

- Lack of structure: the sales presentations from the worst-performing teams present information “the wrong way ‘round.” They lead with content that should be at the end of the presentation, and vice versa.

- Lack of focus: the sales presentations from the worst-performing teams are, like the websites, inner directed. There is no room for the prospect to see themselves in the story.

In future issues I’ll discuss creating an effective web site, creating an effective sales presentation and training your team on its use. But for this issue I’m going to dive deep into something that can be used to great effect in both websites and capabilities presentations, something that is underutilized in life science marketing, something that will help with both of the two major decisions I spoke of earlier. That something is a well-structured life science case study.

The purposes a great life science case study serve in sales and marketing

A well-constructed life science case study offers many benefits, including articulating your unique value and your marketing position.

A life science case study is a short summary of a past engagement with a client. Once you create them, you’ll find they have many uses. You’ll have life science case studies for your sales PowerPoint presentation. You’ll use them on your web site, as a printed or downloadable PDF, as part of a capabilities presentation, or as follow up to a sales inquiry—to name just a few places.

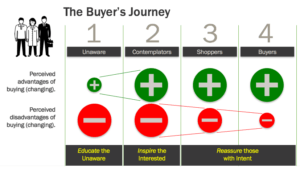

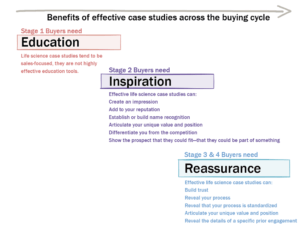

When done well, a life science case study delivers many benefits, throughout the buying cycle, but the benefits do tend to be clustered at the latter stages, when buyers need Inspiration and Reassurance. While a life science case study does serve some purposes at the beginning of the buying cycle, when buyers need Education, there are many tools (such as white papers and videos), that are more effective at Education than a life science case study. Figure 1 details many of the benefits of a properly prepared life science case study and shows how these benefits are spread across the buying cycle.

Figure 1: There are many benefits to a properly prepared and presented life science case study. These benefits occur at different stages of the buyer’s journey; they tend to be focused on supporting the latter stages of the buyer’s journey through Inspiration and Reassurance.

This is an extensive list of benefits. It may seem like a lot for a life science case study or two to accomplish. Yet all this is possible—and in fact, if you follow the right structure, achieving it is surprisingly straightforward. A life science case study can support the two major decisions that your prospects must make on the way to a closed deal: first, deciding that their pain must be addressed and second, qualifying you as a supplier. Because these decisions happen at different points in the buying journey, your prospects need different types of support. In the first case, you must provide inspiration, and in the second, reassurance.

Let’s take a short look at both an inspirational and a reassuring life science case study.

An inspirational life science case study in sales and marketing

Inspiration is very different than reassurance. In essence, inspiration answers the question: “Could my life be better?” with a resounding “Yes, and here’s how!”

When prospects are facing the first major decision I alluded to earlier, they need to decide whether the pain of fixing their current situation will be worth it. Inspiration will help them to decide and act. “Oh, my life could be better (so I’m inspired to act).”

There are many methods of inspiration. An inspirational life science case study might utilize name dropping. For example, “For Pfizer, we completed the formulation of a new compound.” We’re inviting the reader to think, “Oh, they’ve worked for Pfizer, they must be able to help someone like us.” Though most life science sponsors won’t let you use their name, dropping names can be useful, even if you must scale back the use of actual names, as in: “We’ve worked for 8 of the top 10 pharma companies.”

A well-constructed life science case study can inspire your audiences to believe that their life can be better.

Another effective method of inspiration is to focus on the end result, by emphasizing clearly defined metrics: “in only 6 weeks,” “with no 483s,” “to nanometer scale.” An inspirational life science case study doesn’t have to tell the reader how the magic was accomplished, so details are less important to the story. Instead you should focus on the fact that magic is possible—on the inspirational outcome. “Oh, look, you too can achieve this.”

Inspiration typically comes in the form of a single big idea, so you don’t need lots of information; a life science case study that supplies inspiration will be short and focused. Reassurance, on the other hand, typically requires lots of details, so life science case studies that supply reassurance will be longer and more in-depth.

A reassuring life science case study in sales and marketing

An inspirational life science case study answers the question, “Could my life be better?” A reassuring life science case study answers a different question: “Am I about to make a mistake?” This is the main concern of people who are at the end of the buyer’s journey. A reassuring life science case study should supply a clear answer: “No, and here are all the reasons why.”

If an inspirational life science case study focuses on a single big idea, like the dramatic result or the major client name, what should be the focus of a reassuring life science case study?

To answer this question, let’s build an analogy. Imagine your spouse hurts their knee playing softball at the company picnic. You wait a couple of days, but the pain doesn’t subside, so the two of you go to your family doctor. She refers you to an orthopedic surgeon. At the appointment they complete all sorts of diagnostic tests, including some x-rays and an MRI. You finally get to see the surgeon, and she sits down and looks you both in the eye. “Well, your spouse needs surgery. The healing time will be about 6 weeks. Here’s a prescription for a set of crutches. Okay, that’s it; you can see the scheduling nurse on your way out.”

Your spouse is stunned and can’t speak. “But wait,” you say, “what exactly is wrong? What type of surgery? How serious is this?”

The surgeon replies, “Oh don’t worry, I’ve done hundreds of these before. We’re going to go in and snip out a bit of cartilage. Your spouse will be fine, but I wouldn’t recommend sliding into second base any more, okay?”

Together, you leave the surgeon and, since you still don’t have the answers to all your questions, you decide to seek a second opinion. Your experience is identical up to the point when you ask, “What’s wrong? What type of surgery will you be doing?” The surgeon then wheels a cart over to the examination table. On the cart is an anatomically correct model of the human knee, and a bunch of surgical tools. The surgeon walks through the entire operation, step by step. “I’ll start by making from incision here to here,” pointing to the model. “The scar will be about an inch long, and it will last the rest of your life, but it will fade a lot after 6 months, and after 3 years you’ll have to look pretty closely to see it. And then I’ll use tools like these,” holding up some retractors, “to peel back the layers…” And on and on she goes, walking you through every step of the operation in detail—every injection of anesthetic, every slice, every sponge, every snip, every stitch, everything she’s watching for, everything she expects to find, and what she’s going to do when she finds it. And when she’s done explaining the entire operation, she explains every possible outcome, and the probability of each.

A clearly-defined process is reassuring

You and your spouse have consulted two surgeons. If they both had graduated from top-notch medical schools, done their internship in the same hospital, and have identical experience and records of success performing this exact surgery, which surgeon would you choose to operate on your spouse? Which one would you trust to get the surgery right when what’s on the line is incredibly important: the mobility of your spouse?

Most people are clear, “I’d trust my spouse’s knee to the second surgeon.” When I ask “why?” the answers get a little murkier, because reason and instinct are at odds. Reason suggests that the two surgeons have identical experience and records of success, so it shouldn’t matter. But instinct is also speaking; the clarity of the second surgeon does matter—a lot—particularly when the stakes are high and the outcome is uncertain.

Even if your spouse is squeamish and doesn’t want to think about incisions, injections or snipping, you’re making an assumption as you listen to the second surgeon. It’s buried, but it’s there nonetheless. You’re assuming that anyone who can explain the process in such great detail must really know the process inside out. Their explanation of the process allows their expertise to shine through loud and clear. Their explanation acts as “proof” of their expertise.

Your reason can’t decide between the two surgeons; their success rate is identical. But your instinct knows something that your reason is poor at understanding: the concise articulation of a clearly defined, logical process is incredibly reassuring. It builds trust.

Those readers who believe that logic rules all decision making are now scoffing. “The records of the two surgeons are identical; the choice shouldn’t be altered by emotion.” And I’m not arguing that their logic is wrong. The records of the two surgeons are identical, so if the decision is made using the available statistics, the result is a tie. But there is a tiebreaker—it’s the trust that’s built by the second surgeon with her clear explanation.

And that trust, that emotional connection, is invaluable. Those who have studied the science1 realize that few, if any, decisions are made using purely rational processes.

Decisions aren’t made using logic alone

I’ve written elsewhere that decisions involve multiple layers of the brain. The science is clear; humans don’t make decisions using only their rational cognitive functions, which reside in the neocortex. They rely on the deeper brain structures as well, where emotions are processed. At the end of the buying cycle, buyers need reassurance; buyers need trust. These are emotions to which rational justifications might be attached, but neuroscientists have peeled away all the rationalizations and revealed that your prospects, being human, need trust. They need reassurance. A clearly defined, concisely explained process builds this trust.

Just as in the surgical example above, your process, if it’s clearly articulated, will reassure your prospects that you know what you’re talking about.

If you’ve got a process, the prospect is encouraged to assume you must have tackled this particular type of challenge enough times to notice the patterns and build a process in the first place. If you’ve got a process that’s clearly defined step by step, the prospect is encouraged to assume you must be constantly honing your approach, and paying attention to the methods you’re using to do so. If you can articulate your process clearly and concisely, your prospect is encouraged to assume that the process guides your actions; it means much more than a list of steps on a sheet of paper that’s filed in some drawer somewhere.

Your process, when clearly defined, builds trust. Your process, when concisely articulated, reassures your prospects. Your process should be the star of a life science case study that is designed to reassure.

Your organization’s process can be very reassuring; it makes a great focus for your life science case study.

You’ve got a process, don’t you? Of course you do. Unfortunately, for many B2B life science companies, those processes are buried. Buried in the heads of the scientist running the lab, or worse yet, buried in the details of some arcane, complex protocol.

This is one of the reasons that a life science case study is not well utilized in life science sales and marketing. It takes work to articulate your process and show how it applies to a past client engagement. But this is exactly what you must do if you want to build an effective life science case study. This is a new concept for many of you, so I’ll be walking you through a step-by-step process to accomplish this in a coming issue.

But what about peer-reviewed journal articles?

At the top of this article I spoke about the audits of our clients’ web sites that are performed as part of the onboarding process. It’s clear from these audits that many organizations believe that they’re already got great life science case studies. They believe that they can use their peer-reviewed journal articles as a life science case studies. And in fact, many web sites have sections entitled “Case Studies” that are populated with peer-reviewed journal articles. After all, haven’t these articles been validated by some of the best minds in the discipline (the peer reviewers) and published in the most prestigious journals? What more could a shopper possibly want?

Peer reviewed journal articles do NOT make a good life science case study without significant modification.

It’s possible to create an interesting scientific life science case study but let me be frank: a peer-reviewed journal article makes a horrible life science case study. I’ll begin the next article by discussing the several reasons why a peer-reviewed journal article fails to fill either the need for inspiration or the need for reassurance. Till then I urge you to go read a journal article masquerading as a life case study on your website. Does it really inspire? Does it really reassure? (Hint: the answer is almost assuredly “no.”)

Summary

Life science case studies are an underutilized sales and marketing touchpoint. They’re underutilized because few life science marketing teams know how to create an effective life science case study. There are two types: An inspirational life science case study is shorter; it focuses on helping the reader envision how their life could be better by conveying a single big idea. A reassuring life science case study is longer, with more detail; it focuses on helping the reader qualify your abilities to help them with a current challenge.

In the next issue, I’ll dive into the topic of constructing an effective life science case study. Are there rules-of-thumb that should be followed? Of course there are. Until next time.

1Bechara, A., ”The role of emotion in decision-making: evidence from neurological patients with orbitofrontal damage,” Brain Cogn. 2004 Jun; 55(1):30-40

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.