Your archetype is NOT your persona. (Let’s clarify some marketing terminology.)

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 11

, NUMER 1

Summary: There’s a lot of confusion out there between archetypes and personas. Both hinge on common patterns, but we shouldn’t confuse the two. I’ll explore this topic and shed some light on the different uses of the words Personas and Archetypes. I hold out hope that we can agree on common definitions and avoid some of the confusion that comes from the words’ overuse, misuse and abuse

Terminology is extremely useful, so let’s use it carefully.

It’s unfortunate that Marketing, as a discipline, has lots of confusion surrounding many of the terms used in the discipline. This is a real embarrassment, because marketing is the one corporate function supposedly responsible for clear communication. Yet marketers can’t agree on the meaning of words that should be central to rational discourse about our chosen discipline, terms like “brand,” “identity” or “persona.”

Science, like marketing, is a discipline that invents terminology. But science has two advantages over marketing in doing so. First, the words that science invents (prions, Escherichia coli, messenger RNA) are assigned very specific meanings. And second, science drives consistent use of this terminology through the peer-review publishing process. Marketing invents lots of terms (marketing-qualified leads, lead flows, advertorial, brand) but has no mechanism for ensuring consistency in their use, so the meanings remain imprecise (one automation system’s “workflow” might be another’s “campaign”). The result: an overabundance of jargon and a mind-numbing amount of mumbo-jumbo. No wonder scientists are suspicious of marketing.

Need evidence of our lack of specificity? Just ask six marketers for the definition of the word “brand.” You’ll get almost a dozen definitions. Here’s my exploration of the four (!) primary meanings of the word “brand“and a summary of another thirty different definitions!

Science needs the precision that comes with specific definitions. Marketing could really benefit from this precision as well. Unfortunately, our discipline does a poor job of, well, being disciplined—creating a strong, consistent, widely recognized foundation through the use of specific language.

The terms “archetypes” and “personas” are perfect examples, because many people use them as synonyms. (Spoiler alert: they’re not.)

Archetypes and Personas are not the same thing.

The words archetypes and personas are, in some meanings, very close. But using these two words completely interchangeably robs both of their power. For example, in the introduction to the book Buyer Personas, Adele Revella defines the term buyer personas by using the word archetypes.

“In the simplest terms, buyer personas are examples or archetypes of real buyers that allow marketers to craft strategies to promote products and services to the people who might buy them.”

In this case, she is employing the term archetypes according to the first dictionary definition of the word, namely: “A perfect example of a type or group.” But there is a second definition of archetypes, one that is much more commonly used in marketing, so harnessing a less-common definition of archetypes to define personas is just confusing.

So let’s start our discussion by reviewing some definitions.

What is a Persona?

Persona is derived from Latin, where it originally referred to a theatrical mask. And the most common meaning of “persona” is “the public image one presents to the world, perhaps in contrast to their real character.” In marketing, persona is used in two ways, to describe a segmentation of customers (as in: a buyer persona) or to refer to an organization’s public personality (as in: a brand’s persona).

Let’s take a look at these different uses.

Buyer personas.

A buyer persona is a “perfect example” or a characterization of a particular type of person—one who is involved in the buying process. Think of this characterization as a pattern. For example, a “price buyer” is one type of buyer persona, a pattern with certain attributes. As I present it here, the “price buyer” is a very shallow pattern, a persona without much detail. But even just the title of this persona allows us to understand this type of buyer’s motivation (“I want to get the best price, without regard to any potential cost to my relationship with the seller”), behavior (“I’m going to negotiate fiercely”) and attitude (“This is a zero-sum game; if you win, I lose”).

Buyer personas are used to segment an audience, through the characterization of different behavioral, motivational and attitudinal patterns shared by individual segments.

Uncovering the patterns that lead to buyer personas.

We can uncover the relevant patterns that define different buyer personas in multiple ways. Qualitatively, we can conduct in-depth interviews with a small selection of those who fit certain characteristics, in order to look for similarities and identify the patterns. For example, we could uncover buyer personas by interviewing a selection of people who have recently been involved in the buying process. Then we could examine the collection of interview findings and identify distinct patterns of motivation, behavior and attitude.

Quantitatively, we can gather information from large numbers of people, using statistics to uncover any relevant patterns. One obvious example occurs when you’re shopping online and a recommendation comes up at the bottom of the screen. “Frequently bought together…” or “You may also be interested in…” prompts are based on patterns of buying behavior recognized by the site’s algorithms or AI. If you see that on an e-commerce site, your behavior is being used to “segment” you. I should note that this segmentation is not necessarily a bad thing; I’ve been exposed to all kinds of enjoyable new products and services, including movies, music and podcasts, through this type of segmentation.

To identify personas, we’re looking for patterns of motivation, attitude and behavior that already exist among our audiences. The qualitative approach uses deep exploration of a narrow set of subjects; the quantitative approach uses a narrow exploration of a broad set of subjects. Regardless of the approach, the goal is the same: identifying a meaningful pattern that allows us to predict others’ actions, so we can tune our own behavior.

That’s what the recommendation “Frequently bought together…” represents: a modification in the behavior of the seller, based on patterns they recognize across many buyers’ actions.

For buyer personas, there are many different types of insights that allow us to tune our behavior. These can include factors such as:

- why the buying process was initiated

- the goals of the buying process

- the perceived obstacles to purchase

- the steps in the purchase process

- the rationale for the decisions made along the way

These insights make a buyer persona incredibly useful. By identifying and classifying the attitudes, motivations and behaviors of different types of buyers we can focus more specifically on their needs, and sharpen the way we market and sell to them. Buyer personas allow us to identify and predict what our audiences will find most important, believable and compelling. This allows us to tune our behavior and guides us in creating compelling marketing initiatives.

Brand personas.

There’s another use of the word Persona in marketing. To understand this second definition, let’s start with the fact that marketing teams are tasked with clearly defining many aspects of their organization’s public face—their “brand identity.” This includes graphic appearance (logos, symbology, colors, use of images, etc.) and language (tone of voice, messaging, tagline, etc.). When all of these aspects are carefully managed and consistently expressed, they begin to create something similar to a personality.

To see this in action, think of two organizations that compete in the same sector, and consider their public facing personality. For example: McDonalds vs Chick-fil-A or Microsoft vs. Apple. Don’t the differences you perceive feel like a difference in personality? Of course they do. That’s why those brand teams pay so much attention to managing a personality that is consistent.

Figure 1. The differences in how organizations express themselves can feel like a difference in personality—a fact brought to life in this iconic ad campaign: “I’m a Mac. And I’m a PC.”

These personalities are often referred to as a “brand persona.” This usage is less common than buyer persona, but it’s closer to the dictionary definition: “the public image one presents to the world, perhaps in contrast to their real character.”

Both a brand persona and buyer personas are patterns. Buyer personas are patterns of behavior that already exist; a brand persona is consciously and deliberately shaped and codified in order to guide the expression of marketing messages.” Since both use the word Persona in different ways, we’re not being clear.

What is an Archetype?

According to the dictionary, an archetype is either, “a perfect example of a type or group” or “any of several innate patterns in the psyche.” In marketing, an archetype most often references the second definition, drawing on recognized patterns such as the Lover, the Hero, or the Outlaw. This is based on the work of Carol Pearson and Margaret Marks (NEED FOOTNOTE for The hero and the outlaw) which identifies and describes the twelve different families of archetypes—building on the mid-century work of Joseph Campbell, which itself the was based on the earlier work of Carl Jung.

Pearson and Marks revealed how archetypes are often used in marketing to differentiate B2C products and services, particularly those without much innate differentiation. If you’re new to archetypes, consider how an organization with the Jester archetype would act and speak very differently than an organization with the Innocent archetype. The Jester would be fun-loving—think of Pepsi—while the Innocent would be involved in the search for purity and harmony—think of Coke.

Figure 2. Coke is an Innocent brand. Pepsi is a Jester brand.

Figure 2. Coke is an Innocent brand. Pepsi is a Jester brand.

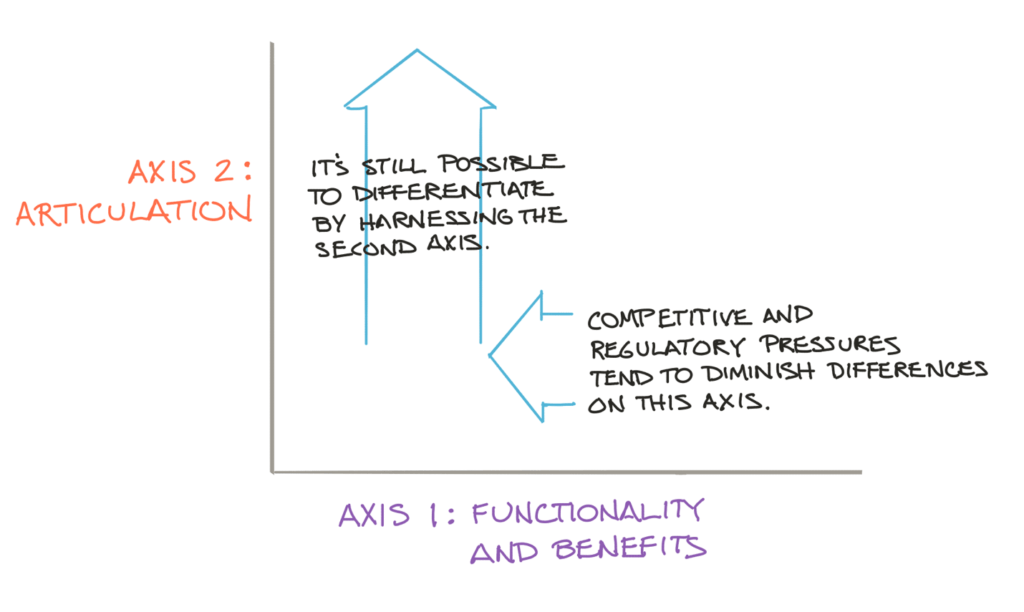

When used to differentiate products or services, archetypes tap into the second axis of differentiation, one that differentiates products and services that have little distinction on the first axis, a difference in function.

Figure 3. There are two fundamental axes of differentiation. For more, read this

Both archetypes and buyer personas tap into existing patterns. Buyer personas are built by recognizing patterns of motivation, attitudes and behavior among external audiences. Archetypes tap into patterns that are culturally ingrained.

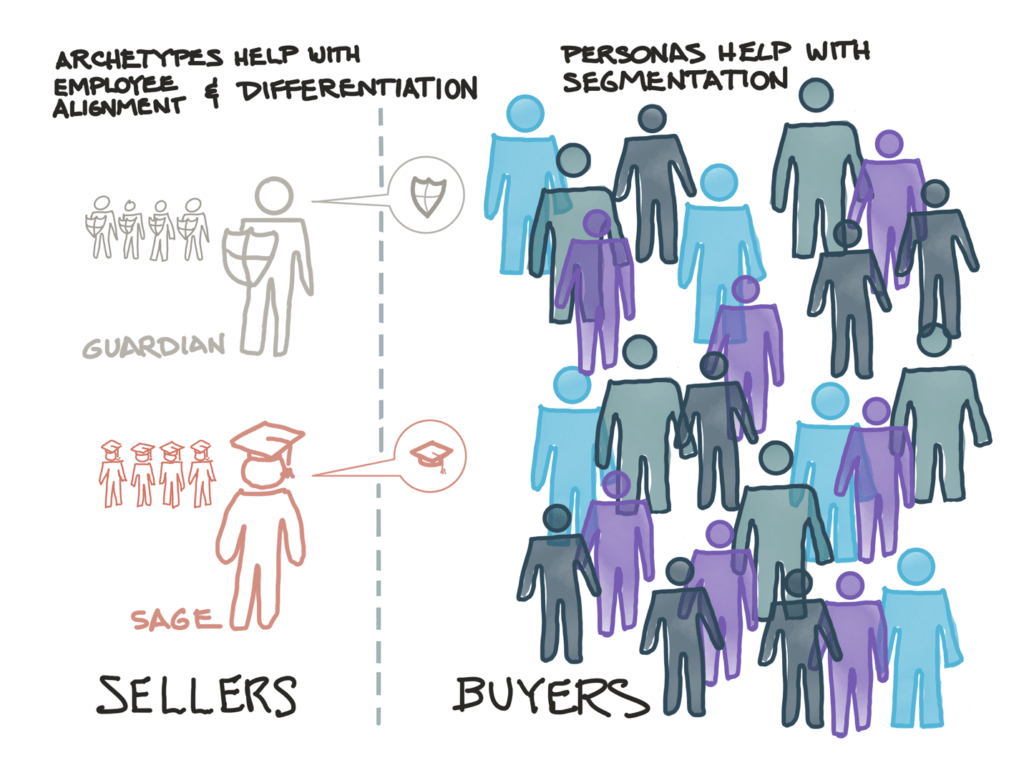

Figure 4. Archetypes are useful in aligning employees and differentiating organizations. Personas are useful in segmenting buyers.

Let’s be straight with our terminology.

Now that we know what all these different terms mean, let’s talk about how we use—or misuse—them.

It’s easy to see how marketing is misusing these terms. A buyer persona is not “the public image a buyer presents to the world, perhaps in contrast to their real character.” In fact, they could more accurately be called buyer archetypes: “a perfect example of a type of buyer.” But that just replaces one confusion with another, because archetypes are already well understood in marketing as cultural patterns rather than audience segments.

So, let’s keep Buyer Personas as a term. It’s useful.

And to minimize the confusion, let’s not use the term Brand Persona. The word “Brand” already has four distinct meanings and Persona already refers to a segmentation. So, if we must, let’s use the term “Personality” rather than Persona, to refer to the combined set of behaviors, messages and attributes that are used to consistently communicate with audiences.

This Personality is colored by the Archetype we choose. An archetype in this case aligns with the common marketing definition of the term, referring to the cultural patterns of which we are all aware.

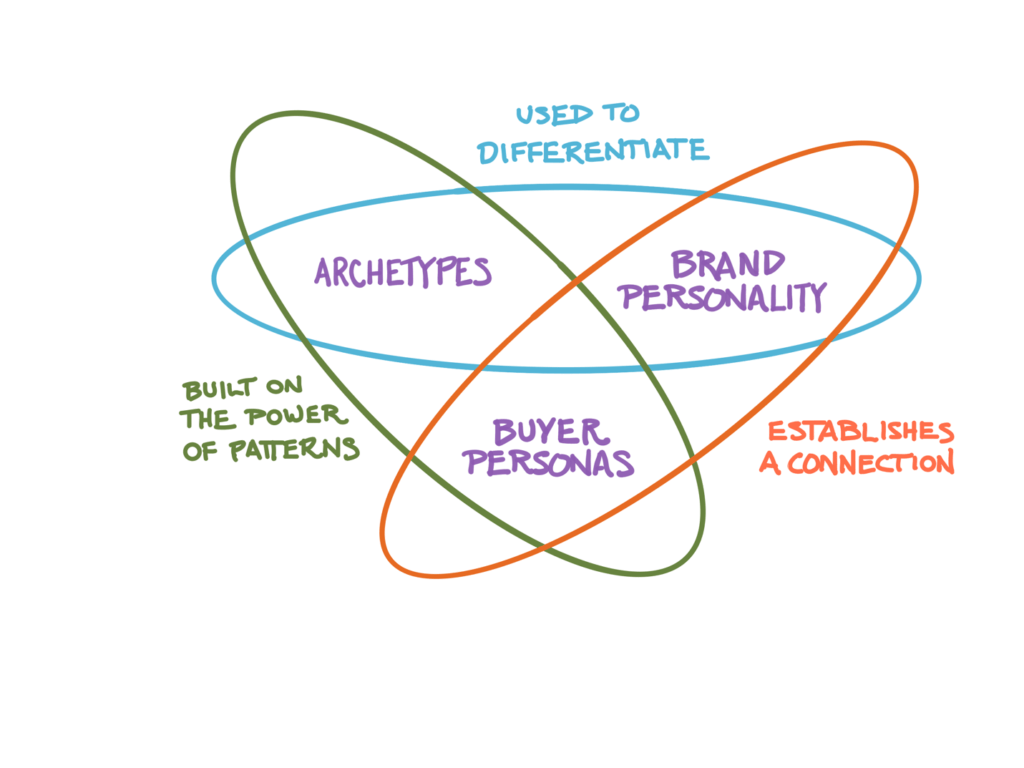

If we use these terms as I propose, then we will clarify the distinctions between them. We will also ensure that we are clear about their similarities, which are explored in the figure 5.

Figure 5. The relationships between the three terms is shown here.

Banish “Brand Persona” from your vocabulary; use “Brand Personality” instead. This will reserve “Personas” to mean an audience segmentation.

Application.

Now that we understand what these terms means and how they relate to each other, let’s consider when they come into play.

- Personas (or Buyer Personas, if that’s a useful mnemonic for you) are used in the research phase, to segment audiences based on their behavior, attitudes and motivation.

- Archetypes are used during the strategy-setting phase, when we want to codify our organization’s tone of voice and behavior. As we have shown here at Forma, archetypes are also useful in aligning employee behavior and increasing team performance.

- Brand Personality is used during the strategy setting phase to establish the combined set of behaviors, messages and attributes which embody the public “behavior” of the organization. It is also used to ensure consistency in ongoing tactical implementation.

Summary.

I propose that we stop using the term “Brand Persona”—it’s too confusing. We’ll call this “Brand Personality” instead; it is intentionally defined, and consistently expressed during the implementation phase, using the “Archetype” as a touchstone to maintain alignment and consistency.

We should only “Personas” (or “Buyer Personas”) to refer to an audience segmentation.

I hope I’ve been able to clear us some of the confusion around these terms. I urge you to join me in the consistent use of marketing terminology.

[i] Revella, Adele. Buyer Personas. Hoboken: Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2015. Print. Page xx.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.